By Mark Olalde, ProPublica

Originally published by ProPublica and the Salt Lake Tribune on December 16, 2021.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

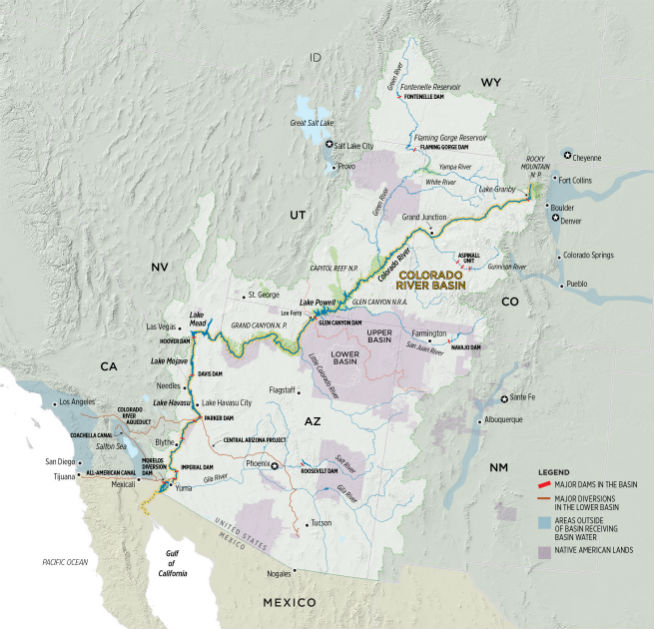

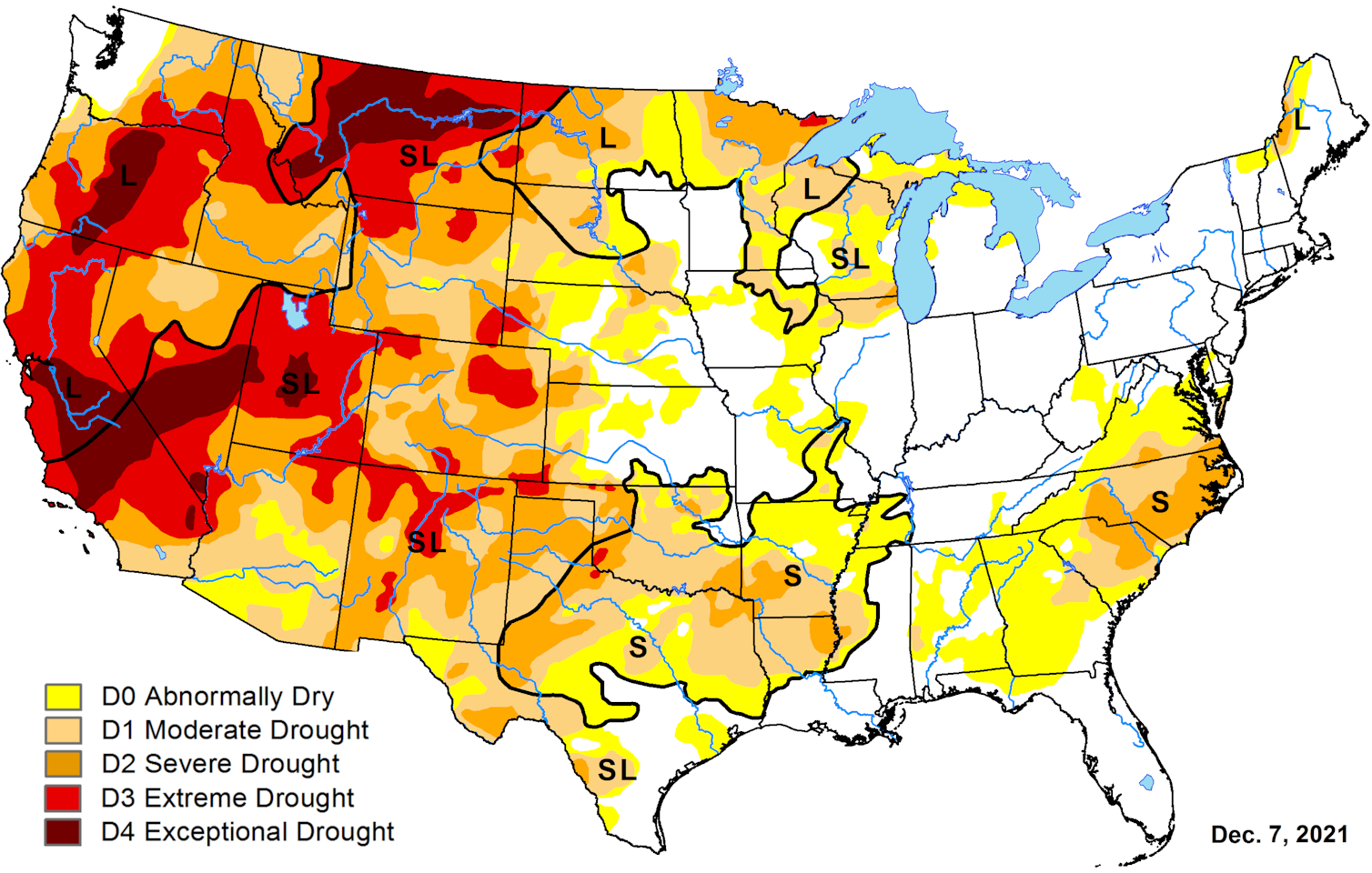

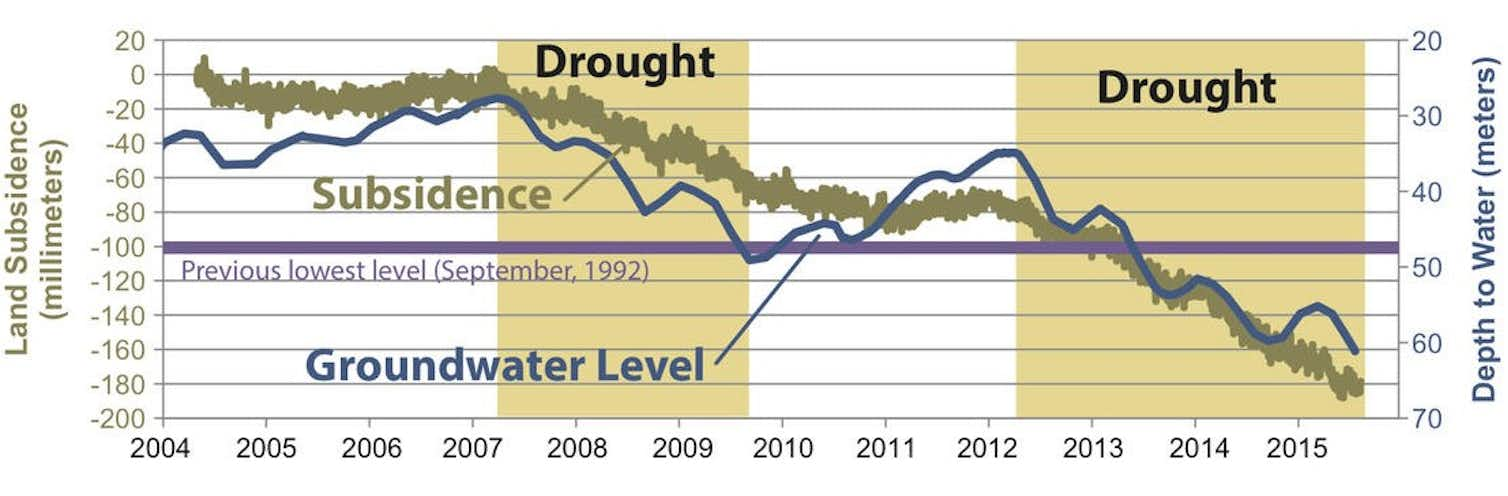

With rising temperatures and two decades of drought depleting the Colorado River, some Southwestern states are spending hundreds of millions of dollars to pay homeowners to tear out their lawns and farmers to fallow their fields.

Water Desk Grantee Publication

This story was supported by the Water Desk’s grants program.

But Utah, the fastest-growing and second-driest state in the nation, is pursuing a different strategy.

Steered by the state’s largest water districts, with the help of their legislative allies, Utah has prioritized the pursuit of new pipelines over large-scale conservation programs. These districts — the public entities that supply water wholesale to cities and towns — have used their influence to secure funding for the costly infrastructure projects, and they have done this while opposing or slowing efforts to mandate conservation, according to a ProPublica review of the districts’ internal communications and every water-related bill filed in the Utah Legislature over the past decade.

In 2017, for example, the water districts opposed legislation intended to more accurately convey to consumers the true cost of water on their utility bills by capping how much of the cost could be covered by property taxes. A similar measure in 2019 passed only after being stripped of limits on water districts’ ability to collect property taxes.

Then, beginning in 2018, the districts and their allies raised concerns about a series of bills to mandate meters for water used on lawns and gardens. Again, the proposals were significantly scaled back.

And in 2020, when a lawmaker wanted to require utilities to find leaks in their systems as a means of conservation, a lobbyist for the districts rewrote the bill, removing the mandates.

Meanwhile, the districts have secured the Legislature’s support for new water development projects that would cost billions of dollars, such as for a pipeline to carry Colorado River water to southwestern Utah and for dams along the Bear River in northern Utah. Without these projects, they say, the state could run short of water within a few decades.

This approach is having an impact beyond Utah’s borders. Other states that have taken sometimes painful steps to cut back on what they draw from the over-allocated Colorado River have criticized Utah for failing to do the same. Utah’s political leaders, though, remain hellbent on securing what they believe is their full share of the river that supports 40 million people, as Arizona, California and Nevada have already.

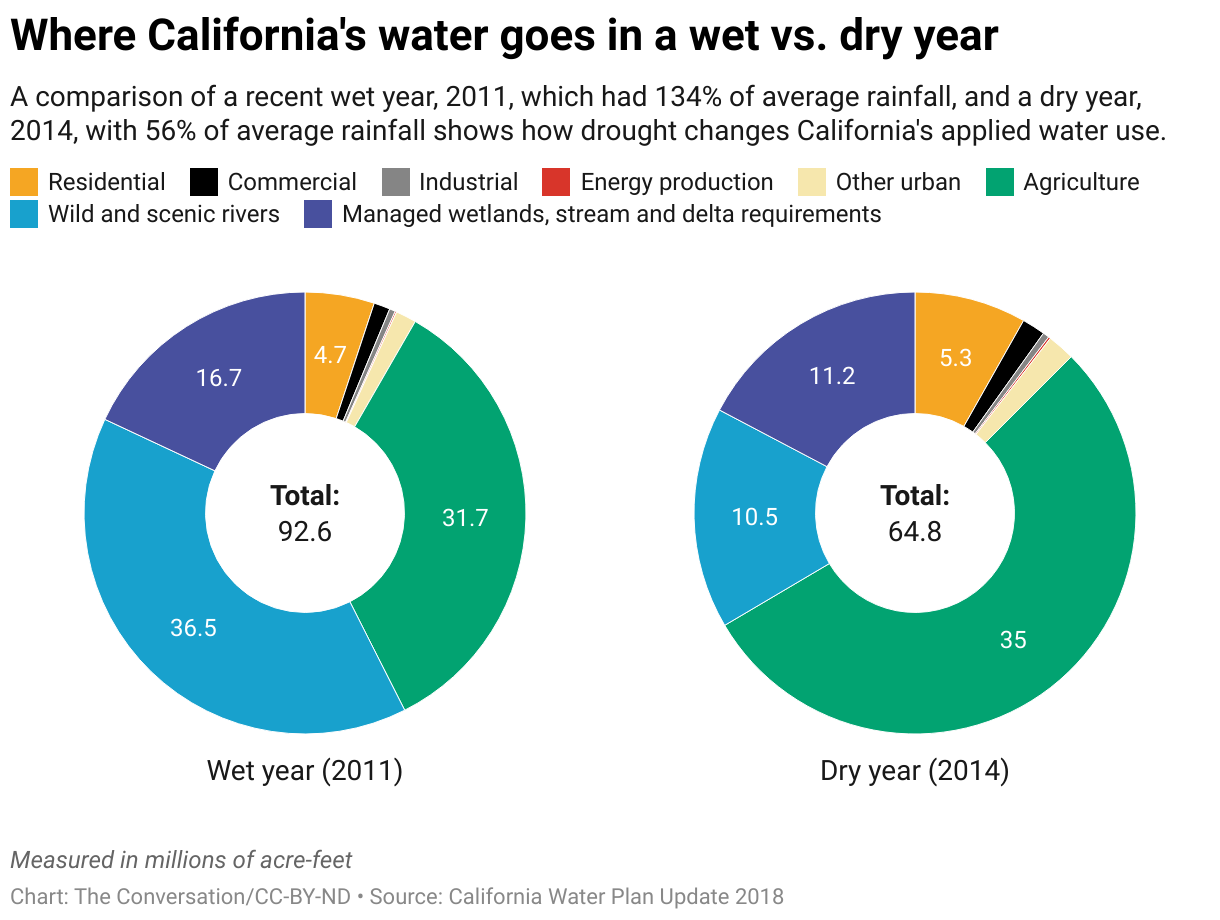

Agriculture consumes a majority of the water used in the West. But Utah farmers have been forced to take less than they have in the past, turning the spotlight to cities and towns where most water is used on landscaping. Yet in a state with suburbs full of lush lawns and tree-lined streets more reminiscent of the Midwest than the Southwest, conservation mandates are politically unpopular.

“Water politics waste more water than anything else in Utah,” said a broker who buys and sells water in the state and who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation from the districts.

Critics call the districts’ prediction that Utah will run out of water without new infrastructure a myth. The state would have the water it needs to continue growing, they say, if it aggressively pursued conservation.

ProPublica found some projections by the state and districts rely on faulty data and questionable cost estimates. A legislative audit uncovered a rash of errors in data on water demand and supply, the very numbers used to justify new infrastructure. And while a district representative told legislators that new projects such as pipelines would be a cheaper source of water for Utahns, their own numbers show conservation has provided water at a fraction of the cost of those projects.

“Everyone realizes that reducing water demand and increasing water conservation is the cheapest source of new water for Utah’s future,” said Rep. Suzanne Harrison, a Democrat who proposed a water conservation bill that was opposed by the districts, “but folks who are interested in developing water and building expensive pipelines don’t really want that conversation.”

Uniting as Prepare60

The influential group that controls Utah water policy is largely unknown to the public, but they’re well known to policymakers. At its core are Utah’s four largest water districts, which work alongside a loose coalition of politicians and interest groups representing cities and rural water users.

The water broker calls the group Utah’s “water OPEC.” A former state senator who clashed with the group over legislation considers them “smug kingdom builders.” But to most people familiar with their power and ploys, they’re the “water buffaloes.”

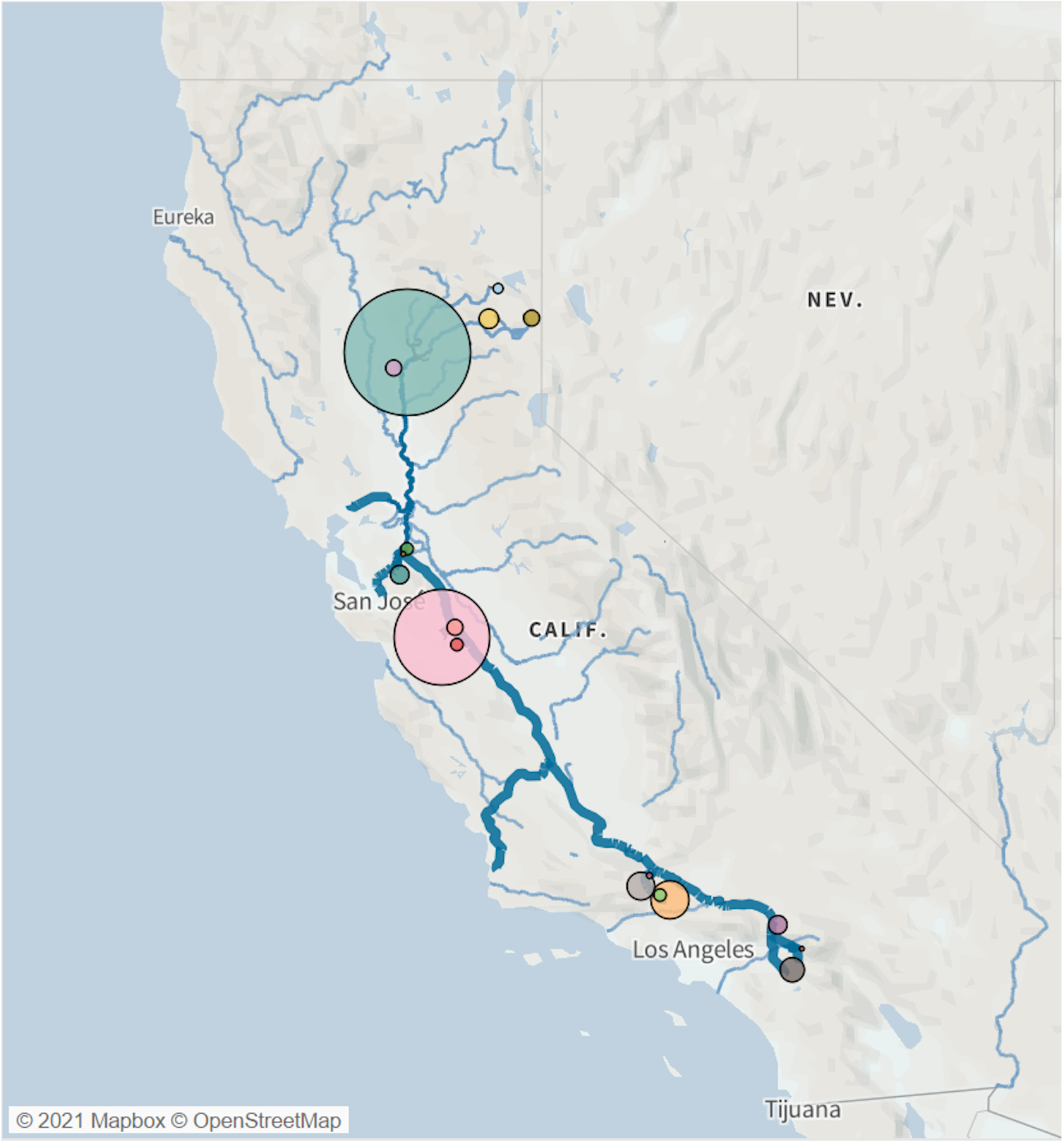

The four largest water districts see themselves on the front lines of a battle to defend Utah’s water rights from neighboring states and prevent shortages as the state grows. These districts — which serve about 90% of Utahns and bring in about a half-billion dollars of revenue annually — secure water at its source and transport it across the state to cities and towns, which in turn sell it to Utahns.

The state’s population is projected to more than double between 2010 and 2060, so the four districts, three of which sell to the cities along the Wasatch Front, teamed up to develop and lobby for a plan to keep pace with that growth. This has given them an organized bloc to push for their ideas. Nodding to the 2060 population projection, they dubbed themselves Prepare60.

The group, commonly referred to as Prep 60, has three stated goals: conservation, defending water rights and developing new water. But they don’t give equal attention or funding to each.

When it comes to conservation, the Prep 60 districts implement measures long common elsewhere in the West. These include, among others, a “Flip Your Strip” program that pays homeowners to rip out curbside grass; rebates for efficient irrigation and low-flow toilets; lining canals to reduce water lost to seepage; demonstration gardens to showcase water-saving landscaping; and financial support for such outreach efforts as television ads in which Utah Gov. Spencer Cox pleads with residents to voluntarily “slow the flow.”

The Washington County Water Conservancy District, a member of Prep 60, is also working with St. George and other southern Utah cities on their first-ever municipal ordinances limiting the size of lawns. California first instituted rules on water-efficient landscaping in 1993, and they’ve become stricter in the years since.

Other Colorado River Basin states say Utah’s investments in conservation are insignificant compared to steps they have taken in the face of climate change. In blistering comments about the Lake Powell Pipeline — which would draw water from a shrinking reservoir along the Arizona-Utah border and send it to Washington County in Utah’s southwest corner — Nevada water officials took aim at Utah water policy.

“What the Utah Board of Water Resources characterized as extreme conservation efforts and not practicable, such as converting or installing more efficient landscapes and creating incentive programs for water conservation, are actually commonly applied in an efficient and effective manner in many other communities,” they wrote in 2020.

Take the Southern Nevada Water Authority, wholesaler to the Las Vegas metro area. Since 1999, that agency has paid residents and businesses to convert grass to water-efficient landscaping. The Central Utah Water Conservancy District, a Prep 60 member and Utah’s largest water wholesaler, didn’t launch a similar program until this year. The Nevada district pays Las Vegas property owners $3 per square foot of grass they remove, compared to a maximum of $1.25 paid by the Utah district. In total, the Nevada district has spent $258 million to remove more than 200 million square feet of turf, while the Utah district has received 364 applications for the funding and paid $15,400.

There’s a similar gap in other conservation spending. Arizona, Nevada and California recently committed $100 million to reduce water use in the next two years alone. Of that, $20 million will come from the largest water district in Nevada, a state about the same size as Utah. The Central Utah district spends several hundred thousand dollars of its own money every year on “water conservation activity” and “water efficient landscaping.” When it does fund conservation, it typically relies on federal dollars, spending $141 million in federal funding between 1995 and 2019. Utah’s Washington County Water Conservancy District spent 445% more on the yet-to-be-started Lake Powell Pipeline than it spent on “conservation” and “public education” combined, according to its three most recent audited financial statements. The district said those years were outliers because the pipeline’s environmental impact was being analyzed.

Meanwhile, the Prep 60 water districts have spent generously on lobbying at the Utah Capitol.

The districts’ most influential surrogate is Fred Finlinson, a Republican who spent 20 years in the state Senate before leaving to lobby his former colleagues. After switching jobs, he married Christine Fox, a Republican who had spent 11 years in the Legislature before joining her new husband to work on water policy and lobbying. The Prep 60 districts have paid their firm, Finlinson & Finlinson, more than $5.3 million since 2014. (The districts said some of that money went to “specialized consulting services” that didn’t involve lobbying.)

In addition to helping found the firm that lobbies on behalf of the four Prep 60 districts, Christine Finlinson collects a paycheck as an assistant general manager of the Central Utah Water Conservancy District. Activists and a member of the district’s board have alleged that this is a conflict of interest because her district sends lobbying business to Finlinson & Finlinson.

Over the summer, the Utah Rivers Council, an environmental group, asked the state attorney general and the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Office of Inspector General to investigate the district’s role in the arrangement and its history of using the firm to lobby against conservation bills. “We are concerned that the personal financial needs or professional whims of the senior staff of the CUWCD have been placed ahead of the needs of Utahns in providing an affordable water supply,” the council’s letter to the state attorney general said.

Christine Finlinson did not respond to requests for comment, but district General Manager Gene Shawcroft said that “the allegations are totally unfounded,” adding that she plays no role in deciding the district’s contracts with her husband.

After the call for investigations, the state’s database of public lobbying disclosures was altered to remove Christine Finlinson’s affiliation with Finlinson & Finlinson.

Challenging Road for Conservation

When lawmakers file conservation bills, they quickly learn who controls the process.

As she campaigned for office in 2018, Harrison, the Democratic lawmaker, repeatedly heard water mentioned as a top issue for voters. So, after she won, she filed a bill to compel water districts to study how to reduce per-capita use.

States don’t all count water consumption the same way, making precise comparisons difficult. But no matter how it’s counted, Utah has one of the nation’s highest per-capita rates of water use.

Harrison’s bill would have set a conservation target based on Denver’s per-capita water use but without mandated cutbacks to reach her goal. She wanted the bill to start a discussion and believed her idea would fly through the Legislature. But there was immediate opposition.

In emails with the water districts’ general managers, Fred Finlinson noted Harrison’s bill had not been “vetted to my knowledge before any members of the water community.” He claimed it would require studies costing millions of dollars, even though Harrison’s bill would have merged its goals with already mandated conservation plans. The water districts’ general managers said they wanted to wait for the completion of a state goal-setting process, which eventually published weaker conservation targets than Harrison had proposed.

The emails also revealed a cozy relationship between Prep 60 and state regulators. The deputy director of the Utah Division of Water Resources at the time, Todd Adams, worked directly with Finlinson to write amendments that weakened Harrison’s conservation targets. He sent the lobbyist a marked-up copy of the bill with a note reading, “Give it a read and let me know what you think and where I screwed up.”

Adams wrote in an email to ProPublica that the agency is open to working with anyone on legislation, including “Legislators, water conservancy districts, cities, water entities, NGO’s and lobbyists.”

Finlinson forwarded the annotated legislation to the Prep 60 leadership. The districts could “let everybody know who is going to destroy their communities,” he wrote, referring to Harrison. “If she isn’t willing to go with this proposals, her bill will likely remain in the House Natural Resource committee for the rest of the session,” he added.

The bill was shelved.

Harrison said, “I learned really quickly as a freshman lawmaker that when you try to address water legislation, you’re quick to get burned.”

In a brief phone conversation, Finlinson told ProPublica, “I’ve tried my best to represent my clients.” He said he preferred to answer questions through email but did not respond to emails from ProPublica.

The outcome for Harrison’s bill was typical for Finlinson, the Prep 60 general managers and their “trusted friends,” as the lobbyist called their legislative allies. As the 2020 legislative session ended, Finlinson noted in an email to his clients that of the 53 bills he was interested in — a majority dealing with water — 52 had gone the way he wanted. The only bill that had Finlinson’s approval but failed to advance ended up signed by the governor a year later.

Among the legislation Finlinson helped shape were bills proposed by state Sen. Jacob Anderegg, a Republican. Tens of thousands of Utah property owners only pay a connection fee for unlimited use of untreated water outdoors, leading to excessive watering of landscaping. Known as secondary water, it typically comes from lakes and rivers and could otherwise be treated and used elsewhere. Anderegg saw potential savings by requiring meters for secondary water.

In 2018, Anderegg filed a bill in the Senate to require secondary water meters on most connections statewide and co-sponsored a House bill to include secondary metering in conservation plans. Both bills died.

The Prep 60 general managers acknowledge secondary meters encourage conservation. Data from the Weber Basin Water Conservancy District — a northern Utah Prep 60 member that spent more than $16 million installing meters — shows residents reduced outdoor water consumption by 23% simply because they could see how much water they used. No rate increase was necessary.

However, when Anderegg tried again, Finlinson, in emails to the Prep 60 general managers, worried that if lawmakers put money toward secondary metering, there would be less funding for water infrastructure such as dams.

Asked if the group decides what water legislation lives or dies, Anderegg answered bluntly: “Yes. Absolutely.”

Even when Finlinson and the large water districts don’t stand in the way of conservation measures, other lobbying groups, politicians and rural districts often oppose them. In the case of Anderegg’s bills, small districts and cities also balked at the cost of the meters.

“They all work together on water,” Anderegg said of Utah’s water districts, large and small. “They all shoot an email out to everybody in their group, and then all those people go talk to their elected officials, and then their elected officials don’t want to get sideways from their water buffaloes and come up here and say, ‘I’ve got serious issues with your bill, Sen. Anderegg.’”

Anderegg eventually passed two bills. His intent was to mandate secondary water meters on all buildings statewide, but he was forced to remove that requirement. As enacted, one bill requires meters on new construction, while the other exempts certain jurisdictions from the rule. Finlinson bragged about the outcome, telling his clients that secondary metering passed “in its substituted splendor.”

Washington County Water Conservancy District General Manager Zach Renstrom said lobbying only gets the Prep 60 districts so far. “If I had the ability to go to the Legislature and tell them what to do, that’s giving me a lot more credit than I deserve,” he said.

Even with Prep 60’s influence, it’s difficult to persuade lawmakers to mandate large-scale conservation, so they must rely on voluntary measures, said Shawcroft, who is the Central Utah district’s general manager and has a non-voting seat on the Legislature’s water committee. “Because our Legislature thinks ‘mandate’ is a word of the dark side, we try to focus on things that make sense and are doable. To the degree we can, we will attempt to influence conservation bills that make sense, that are frankly doable and passable.”

The aversion to conservation mandates has led lawmakers to discuss solutions to the drought that included prayer and a national pipeline network to transport water from Eastern states to the West. Any less ambitious solution would be “nonsense,” said Republican state Sen. David Hinkins, the co-chair of the Legislature’s water committee.

Support for Pipelines and Other Projects

As the sun rose over southwest Utah one morning this fall, the banging of hammers and clattering of wood echoed through a new subdivision going up in St. George, the nation’s third-fastest growing metro area. “For sale” signs stood in front of some recently constructed homes, while others were already occupied. Sprinklers showered verdant lawns and sidewalks, the runoff streaming down gutters along the streets of this subdivision that not long ago was open desert.

The scene came courtesy of the Washington County Water Conservancy District, which supplies the vast majority of municipal water to the roughly 180,000 people in the county. When the district changed leadership in early 2020, Finlinson sent the outgoing general manager a note of congratulations on a “job well done to the person who has done his best to cover the red sands of Washington County with water.”

The new general manager, Renstrom, is tasked with keeping the water flowing. According to the district and the state, that requires pursuing perhaps the most controversial water project in the nation, the Lake Powell Pipeline.

Renstrom has heard the criticism of southern Utah’s conservation efforts. According to the district, water use in Washington County has over the past two decades dropped from 439 gallons per person per day to 271 gallons. But conservation won’t be enough to keep the area growing, he said, especially as a changing climate threatens the area’s main source of water, the Virgin River: “If I have a biblical drought, the Virgin River’s toast.”

The Colorado River is also suffering. Flows in recent years are down 19% compared to the average during the 20th century, according to research from Brad Udall, a water and climate scientist at Colorado State University. If individual states move forward with new projects to draw from the river while their neighbors are cutting back, it could upend the agreement that allocates the river’s water. “The last 20 years should be an enormous wake-up call that we need to rethink water planning in the West,” he said.

Over immense opposition from inside and outside Utah, Renstrom and state leaders are pushing the 140-mile pipeline to take up to about 85,000 acre-feet of water annually from Lake Powell. In the Legislature, resolutions and legislation supporting the Lake Powell Pipeline and the Bear River Development Project, which would send water from the Utah-Wyoming-Idaho border to Utah’s population center on the Wasatch Front, have had an easier path than bills calling for conservation.

“You can say that conservation alone will save us. It absolutely will not,” Shawcroft, of the Central Utah district, said.

Since 2015, lawmakers have approved bills to pay for this infrastructure. One created a restricted account to fund the Bear River and Lake Powell Pipeline projects and replace some federal water infrastructure. The account was seeded with $5 million from the state’s general fund. Another bill allocated to it one-sixteenth of a percent of all state sales tax revenue. The account has since accumulated more than $95 million.

Safeguarding that money is a priority for Finlinson and Prep 60.

Critics say the districts are blindly pursuing new water infrastructure. Initial projections showed water from the Bear River project would be needed by 2015, but the Weber Basin district now says it won’t be needed until at least 2060. Environmentalists argue this shows the project wasn’t necessary in the first place and the money would be better spent on aggressive conservation efforts.

Tage Flint, the Weber Basin district’s general manager, said he’s proud of the project’s delayed timeline because it shows “we’ve done much better in water conservation from our current sources and stretched them further.”

Plans Based on Faulty Data

As Utah amasses a war chest to tap more water from the Colorado and Bear rivers, data used to justify the projects doesn’t pencil out.

Responding to concerns about the accuracy of projections on how much water the state will need, Utah’s Office of the Legislative Auditor General investigated, casting doubt on the claim that the state will run out of water without new sources. “It is widely recognized that there are fundamental problems with the way the state’s water use data is gathered and submitted by local water providers,” the auditor general’s 2015 report stated.

The audit found some Utah cities reported different water use numbers to the state than they reported internally. One city’s officially reported “water use for 2012 was the water use of another city with an identical name in the state of New York,” the audit said. The audit also found cities and water districts had rapidly added to their supply from local sources, such as converted agricultural water, but the state’s projections showed an inexplicable slowing in the growth of supply if projects like the Lake Powell Pipeline weren’t built.

The state agencies charged with protecting and developing Utah’s water — the Division of Water Rights, the Division of Water Resources and the Division of Drinking Water — acknowledged flaws in their data.

But the state’s political establishment and Prep 60 water districts continue to cite that data to prove that Utah is on the verge of a shortage. They say their internal numbers are sound and that state water accounting has improved, pointing to a 2017 legislative audit that found the state had begun cleaning up its numbers.

The state justified the need for the Lake Powell Pipeline to federal officials using projections that show residents in Washington County will reduce per-capita water use from 302 gallons a day to 240 gallons by 2045, a level of consumption that’s still higher than most of the country. Their projections continue for another 30 years, to 2075, but show no further decline in use. They also show leaks and other water losses consuming 15.4% of the district’s water, higher than the estimated loss of a typical Utah municipality, while projecting the losses won’t decline before 2075. The water district said they are making progress addressing water loss and that number would be updated.

Their cost estimates for water infrastructure also appear to be based on questionable figures, according to Zach Frankel, founder of the Utah Rivers Council and longtime critic of the Prep 60 districts, who hired a researcher to vet the numbers.

In 2013, the Division of Water Resources published a draft list of $19.8 billion worth of water projects needed to keep pace with growth. The following year, Prep 60 released a similar analysis with a $32.7 billion price tag. Last year, Prep 60 updated its estimates to $47.7 billion for projects, maintenance and conservation, some of it paid by businesses and homeowners.

“They’re fantastical propaganda,” Frankel said of the estimates.

He noted that the state’s estimate includes such odd items as $3 billion for a water district’s “master plan” that won’t be needed until 2100 and nearly $1 billion for projects that the group’s research suggests already have funding.

Shawcroft defended Prep 60’s higher estimates, saying the group’s methodology, which was reviewed by an engineering trade group, was more detailed than the state’s and accounted for inflation and the need to replace infrastructure every 50 years.

Despite uncertainty about the cost, Prep 60 contends spending billions of dollars for new water infrastructure is cheaper than conservation and the only way to have adequate water. Conservationists say Prep 60 is wrong on both points.

Studies have found it cheaper to invest in conservation and purchase water from local sources, when those options are available. Estimates for the Lake Powell and Bear River projects range from more than $1 billion to more than $2 billion each. The Central Utah Water Conservancy District analyzed the average cost for its past conservation projects, and tapping new Bear River water could be up to eight times more expensive than conserving an equal amount of water and new Colorado River water could be 14 times more expensive, ProPublica found.

The water broker, who consistently monitors water prices, said pursuing costly construction projects over conservation and other alternatives is “bending over a dollar to pick up a dime.”

The broker pointed to state data that shows Utah lost 200,000 acres of farmland during the most recent five-year reporting period, much of it converted to residential development, which uses less water than farming. “More farm water comes out of production than the cities can absorb annually,” the broker said. “There is a glut of water.”

Bart Forsyth, the general manager of the Jordan Valley Water Conservancy District, a Prep 60 member, said it’s not always cost effective to buy and treat water from farms that have ceased production.

Growth and cost aren’t the only considerations. The Bear River Development Project, because it would divert more water from the Great Salt Lake, must also account for its impact on the lake, which is already at a record low. If the project causes the lake’s water level to fall even further, more of the lake bed will dry out, creating airborne dust laden with toxic metals from industry and fertilizer runoff near a metro area already plagued by poor air quality.

Again, proponents of this pipeline support their argument with suspect data.

The state asserts the project will only lower the lake 8.5 inches. But environmentalists like Frankel believe it will drop several feet, pointing to historical studies of the relationship between the Bear River and the lake level.

The state supports its position with a white paper authored by a Utah State University professor who compiled research on the Great Salt Lake. To answer how much the Bear River project would lower the lake level, he turned to a Division of Water Resources employee who had done modeling on the lake. Instead of citing a peer-reviewed study to support the 8.5-inch figure, the white paper points to their “personal communication.” The professor acknowledged to ProPublica that the number should be treated with skepticism until the state’s model is published and reviewed. Still, the number has been accepted as gospel at the Utah Capitol, with lawmakers and state reports citing it.

Future Priorities

It has likewise become widely accepted at the Utah Capitol that conservation alone will never satisfy the state’s demand for water.

During a legislative meeting in September, Brian Steed, executive director of the Utah Department of Natural Resources, addressed the Legislature’s leadership, who were seated around an ornate, U-shaped wooden table in the Capitol. He was there to discuss $100 million in federal COVID-19 relief money the state had set aside for water issues. Steed told lawmakers he wanted half of it spent on secondary water metering. Utah has 260,000 secondary connections, 85% of which are unmetered, and installing meters would bring massive water savings, he told them.

“This sets aside the need for additional buildout of water infrastructure,” Steed said, “and as we grow and have additional pressure, that additional conservation is really what’s going to have to take place in order for us to grow like we’d like to.”

Legislative leaders on both sides of the aisle responded favorably. (They have since approved Steed’s proposal, and the governor suggested spending an additional $200 million of federal money on secondary meters.) It appeared the worsening drought and availability of federal funds had refocused the state on conservation.

But as Steed stepped into the corridor outside the hearing room, a lobbyist approached. Instead of spending all that money on secondary water meters, the man asked, couldn’t Steed carve out a few million dollars for a reservoir?

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.