As the climate change-fueled Colorado River crisis worsens, hundreds of water leaders from each of the seven basin states will gather in Las Vegas next week for the annual Colorado River Water Users Association Conference.

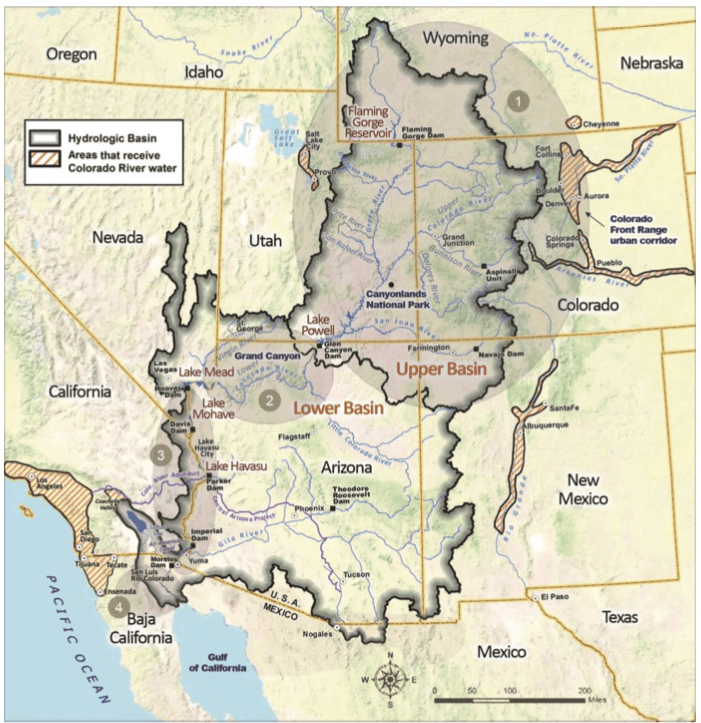

The backdrop to many of policymakers’ discussions is sure to be one of the most important legal documents governing how the river’s waters are shared: the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which divvied up flows between the upper basin and lower basin. But this agreement is a relic of the 20th century. Those flows — totaling 15 million acre-feet, with 7.5 million for each basin — no longer exist, if they ever existed in the first place. The river was overallocated to begin with, and hotter and drier conditions mean flows will continue to dwindle.

These realities have some experts talking about how best to continue dividing the waters within the confines of the century-old agreement while tweaking it to adapt to 21st century conditions. Many water managers agree that renegotiating the compact is not realistic because it would require the agreement of too many competing interests as well as congressional approval. But it also may not be necessary.

“I think we can come to agreement around an appropriate response to these reduced supplies without going through the brain damage of renegotiating the compact,” said Anne Castle, a senior fellow at the University of Colorado’s Getches-Wilkinson Center, who will be moderating a panel at CRWUA.

Eric Kuhn is one of the thinkers proposing that basin states adopt something called a nonstationary set of compact guidelines. Kuhn is an author and former director of the Glenwood-Springs-based Colorado River Water Conservation District. He says that instead of allocating 7.5 million acre-feet annually each to the upper basin (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico) and lower basin (California, Nevada and Arizona), the river should simply be split down the middle: Each basin gets half of the river’s flows, however much that may be.

“A set of guidelines that are based on a stationary set of rules for a nonstationary river is not going to lead to success,” Kuhn said. “We have to consider adopting a more flexible system that is tied to how much water there is in the upper basin.”

Kuhn laid out the concept at a presentation at the Colorado Mesa University Upper Colorado River Basin Forum last month. He also pointed out that requiring the upper basin, where most of the river’s flows originate as snowpack, to contribute the same fixed amount each year despite declining flows means that the upper basin is unfairly bearing the brunt of climate change. Under the compact, the upper basin is required to deliver the lower basin’s 7.5-million-acre-foot share or risk mandatory cutbacks.

“In the upper basin for a decade, we have been talking about the upper basin squeeze,” Kuhn said. “It’s when the flow goes down, but you have fixed commitments. That was somewhat theoretical until a few years ago.”

So far, it’s unclear whether Kuhn’s idea is one that is being seriously considered by water managers. But it has been gaining traction among academic circles, especially in the past few years as river flows have declined at unprecedented speed. This year’s upper-basin flows into the river’s second-largest reservoir, Lake Powell, ranked second worst, at 31% of average, despite a near-normal snowpack.

Climate scientist Brad Udall has found that flows at Lee Ferry — the dividing line between the upper and lower basins and where upper-basin deliveries are measured — have been about 20% less over the past 22 years than in the 20th century. A river system that once produced 15 million acre-feet has now dwindled to just 12.4 million.

Tying the upper basin’s delivery obligations to the variable river hydrology instead of a fixed number would be a way of solving the “significant math problem” where usage exceeds supplies, according to Castle. The concept could be adaptable to changing conditions year over year, she said.

“It could be in effect while supplies continue at the level we have been experiencing and wouldn’t continue if supplies go up in the future,” she said. “So there could be a return to previous delivery levels if there’s sufficient inflow in the river to support that. I don’t think it has to be thought of as a permanent change, but a mechanism that is triggered by some measurement of low levels of supplies.”

Law of the river should bend, not break

Karen Kwon and Jennifer Gimbel of the Water Center at Colorado State University last month released a paper called “Quenching Thirst in the Colorado River Basin.” The paper is devoted to understanding the historic issues that have shaped water use in the basin so that “the historical doctrines can bend to the needs of the present and future without eroding a foundation upon which we all stand.”

“There is a valid reason for asking that question of why something that was written in 1922 … why don’t we just redo it?” Kwon said. “But entire economies and societies have been built off the understandings and infrastructure that exists.”

Kwon, who is also moderating a panel discussion at CRWUA, hopes the paper will provide historic background and context for future negotiations and discussions about interim operating guidelines for reservoirs Powell and Mead. Achieving flexibility and parity between basins while staying within the framework of the compact should be the goal, she said.

Who gives?

But getting both the upper and lower basins to agree to flexible allocations based on annual river flows means they each must give up something — a tricky and as-yet-unlikely prospect. The framers of the compact reserved 7.5 million acre-feet for the upper basin because it wasn’t developing as quickly as the lower basin. If states relied solely on the system of prior appropriation where older water rights get first use of the river, thirsty and fast-growing California could have used up the water decades ago, leaving none for the slow-growing upper basin.

The upper basin currently uses about 4.4 million acre-feet per year. The lower basin uses close to its full 7.5 million acre-feet.

“One of the reasons we need to stay within that framework is because that is what protects us in the upper basin,” Gimbel said. “The only way to protect us getting our fair share of the river was to allow us to develop over time.”

But upper-basin water managers are also reluctant to admit that their states probably won’t grow to use their full amount and jealously guard their apportionment. A February white paper by the Center for Colorado River Studies says these unrealistic future water-use projections by the upper basin make it hard to plan for a water-short future. Still, despite shortages, recently completed Basin Implementation Plans for each of Colorado’s river basins lay out a wish list for millions of dollars’ worth of future water-development projects.

“Bringing new water development into the equation makes the problem worse for everybody, and I don’t see how that can be part of an equitable solution,” Castle said.

Upper-basin water managers argue that their states have been taking shortages for years: When flows are low, they are forced to use less and can’t just draw down an upstream reservoir as can the lower basin with Lake Mead.

Lower-basin water managers may not want to allow a more flexible delivery obligation for the upper basin because it would probably mean that in dry years they would get less than the full 7.5 million acre-feet promised under the current interpretation of the compact.

Complicated politics

The politics are really complicated, said Kathryn Sorenson, director of research at the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University and former director of Phoenix Water Services. People tend to get very excited about new technologies that could increase supplies — for example, desalination plants on the California coast — but balk at further cuts to water use.

“It’s easier to put those ideas forward than to put forward ideas about using less,” Sorenson said. “So that gives you some idea of what a lower-basin perspective might be.”

Both the upper basin and the lower basin have valid points, Kwon said. Sticking to what was promised to them under the compact, which has governed river operations for a century, makes sense. But navigating a water-short future will require moving beyond who is right and who is wrong. Anything else is just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic, Kwon said.

“All of those statements are accurate, but we need to rise above it,” Kwon said. “I hope that we can find a way to have a discussion that protects people’s interests without just outright staking positions, but recognizes and honors interests so we can move the boat instead of just moving the deck chairs.”

This story ran in the Dec. 12 editions of The Aspen Times, Vail Daily, Steamboat Pilot & Today and the Sky-Hi News.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.