By Allen Best

Barring epic snowstorms during the next four months, reservoirs on the drought-strapped Colorado River will enter new territory in 2022, likely unable to fill such basic missions as generating hydropower.

In response, the reservoirs’ owner, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, is moving quickly to create work-arounds.

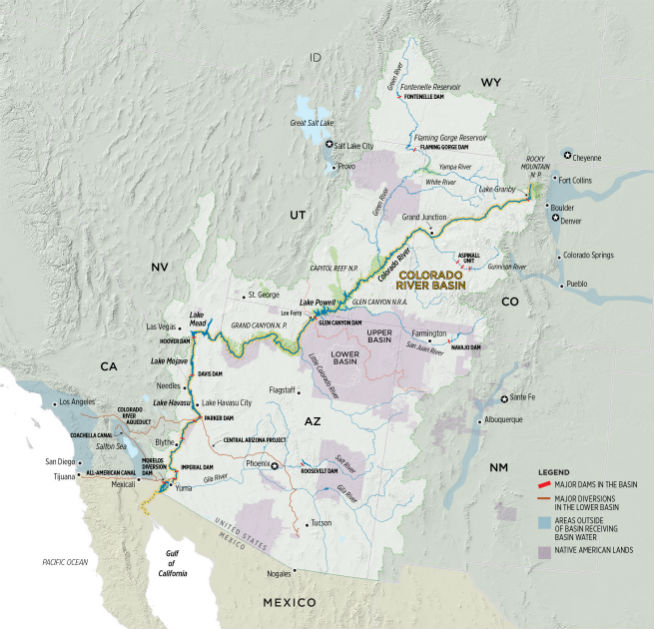

The Colorado River Basin serves seven states and Mexico. It is divided between the Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, and the Lower Basin consists of Arizona, California and Nevada.

“We simply must focus on short- and near-term operational challenges in both the Lower Basin and Upper Basins,” said Camille C. Touton, the recently sworn in commissioner of Reclamation.

But it is the Upper Basin’s Lake Powell that is causing the most concern right now. “We face unprecedented operational challenges at Glen Canyon Dam in a matter of mere months, even weeks,” she said. “Depending on the hydrology, Powell could decline to fall below minimum power pool for long durations.”

The U.S. Department of Interior has made clear its intention to protect lake levels, to ensure protection of the “structural integrity of the infrastructure,” said Tanya Trujillo, the undersecretary for water and science at the agency.

“We at Interior have a federal responsibility to protect the populations we serve,” she said in the final session of the Colorado River Water Users Association Conference in Las Vegas on Dec. 16. “That includes protecting the infrastructure. I have asked (the Bureau of) Reclamation to develop options for consideration in case we see these dry trends continuing.”

What those options might be isn’t clear yet.

Bart Miller, water program manager at Western Resource Advocates, said the water crisis is an opportunity to accelerate water conservations. “We have a real need to act in the next couple of years,” he said.

Comments in Las Vegas alluded to the sobering realities. “All hands on deck,” said John Entsminger, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

Colorado and other basin states have tightened water use since 2002. As documented at Powell, however, the belt-tightening lags what is needed. The pace must be hastened. Exactly how is the question facing Colorado and other states.

Projections show a high risk of continued drying. The two big reservoirs, Mead and Powell, in January 2000 were at 95% of capacity with a combined storage of 47 million acre-feet. By April 2022, they are projected to be less than 30% full with a combined storage of 15 million acre-feet.

Both reservoirs reached historically low levels last summer, holding the least amount of water since they began filling in the 1930s and 1960s respectively. The inflow into Powell last spring and summer was the second lowest on record.

Elevation 3,525 feet is the line in the sandstone established by water managers at Glen Canyon. That will provide a 35-foot buffer above the level below which hydropower cannot be produced. Modeling by the Bureau of Reclamation in December showed a 47% chance that Powell could drop below the target level for ensuring continued safe hydropower generation as soon as 2023.

“Everything associated with Lake Powell is critical to operation of the whole basin,” said Patrick Tyrrell, Wyoming’s representative on the Upper Colorado River Commission.

“We’re not quite sure how the lake will operate if that water elevation approaches the top of the penstocks,” he said. It’s also not clear how water can be released from the reservoir at that lower level, sometimes called dead pool, he added.

Water levels at Powell had declined to within inches of 3,525 this year before the Bureau of Reclamation released water from upstream reservoirs in Colorado and Utah beginning last July.

Looking ahead, officials said aggressive conservation will be key and Las Vegas’ efforts are among those being watched closely. Still rapidly growing, now with 2.3 million residents, the Southern Nevada Water Authority, which serves the city and its suburbs, relies upon the Colorado River to provide 90% of its supplies in a valley that gets less than 4 inches of rainfall a year. Yet even as the population has grown 52% in this century, river consumption has declined 23%.

Las Vegas has achieved this feat by using both carrots and sticks. It may not be noticeable on the Strip because the Bellagio fountains still put on a show and the toilets still flush. In the new suburbs, though, you see almost no grass in front yards, and it’s limited in backyards.

Tightening in Vegas continues. Colby Pellegrino, deputy general manager for resources at Southern Nevada, reported at the conference proposals to trim water use at existing golf courses and ban water for new courses. Swimming pools will shrink in size. And a new Nevada law prohibits Colorado River water use on non-functional turf by 2027.

Water deliveries to Arizona, California and Nevada have declined 22% from 2002 and 2020. More cuts are coming. During the conference in Las Vegas, representatives of the three states signed an agreement known as the 500+ Plan, that requires them to cut 500,000 acre-feet in 2022 and 2023. The plan also requires the three states to pool a collective $100 million, to be matched by a grant from the federal government, for implementation of water efficiency and conservation.

What about the upper-basin states? They have never used their full legal entitlement to river water, and Utah, in particular, wants to build a pipeline from Powell to the rapidly growing St. George-Hurricane area.

In Colorado, agreement about the need for tempering demand has been coalescing. Miller, of Western Resource Advocates, points out that operational adjustments, such as the Upper Basin reservoir releases this year, rely upon existing water, and cloud-seeding to generate more snow cannot solve the problem.

That leaves conservation as the area for more fruitful work to match the rapidly changing climate in the Colorado River Basin.

Past agreements in the Colorado River Basin show a long gestation time that can then emerge into policy given certain political climates. The current situation on the Colorado River provides that opportunity, say John Fleck, of the University of New Mexico’s Department of Economics and Water Resources Program, and Anne Castle, of the Getches-Wilkinson Center at the University of Colorado-Boulder.

“State and federal water officials should seize this opening, cognizant of its likely limited duration, and cement new agreements that steer river operations in a more sustainable direction,” Fleck and Castle say in a recent article. “Well-timed and explicit federal direction may be necessary to catalyze the already ongoing discussions.”

Long-time Colorado journalist Allen Best publishes Big Pivots, an e-magazine that covers energy and other transitions in Colorado. He can be reached at allen@bigpivots.com and allen.best@comcast.net.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.