By Jerd Smith

Utah’s Flaming Gorge Reservoir, which Colorado River officials have used twice during the past two years to add water to the rapidly deteriorating river system, likely only has enough water left for two more emergency releases, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Last summer, Reclamation ordered the release of 125,000 acre-feet of water from Flaming Gorge to help keep Lake Powell from falling too low to produce power. Then, earlier this summer, Reclamation announced that it would release another 500,000 acre-feet of water from Flaming Gorge and hold back 480,000 acre-feet in Powell instead of releasing it to Lake Mead, as it would normally do.

Another 30,000 acre-feet was released from Colorado’s Blue Mesa Reservoir last summer, which along with Flaming Gorge, New Mexico’s Navajo, and Powell itself, was supposed to act as a critical savings account for the river system.

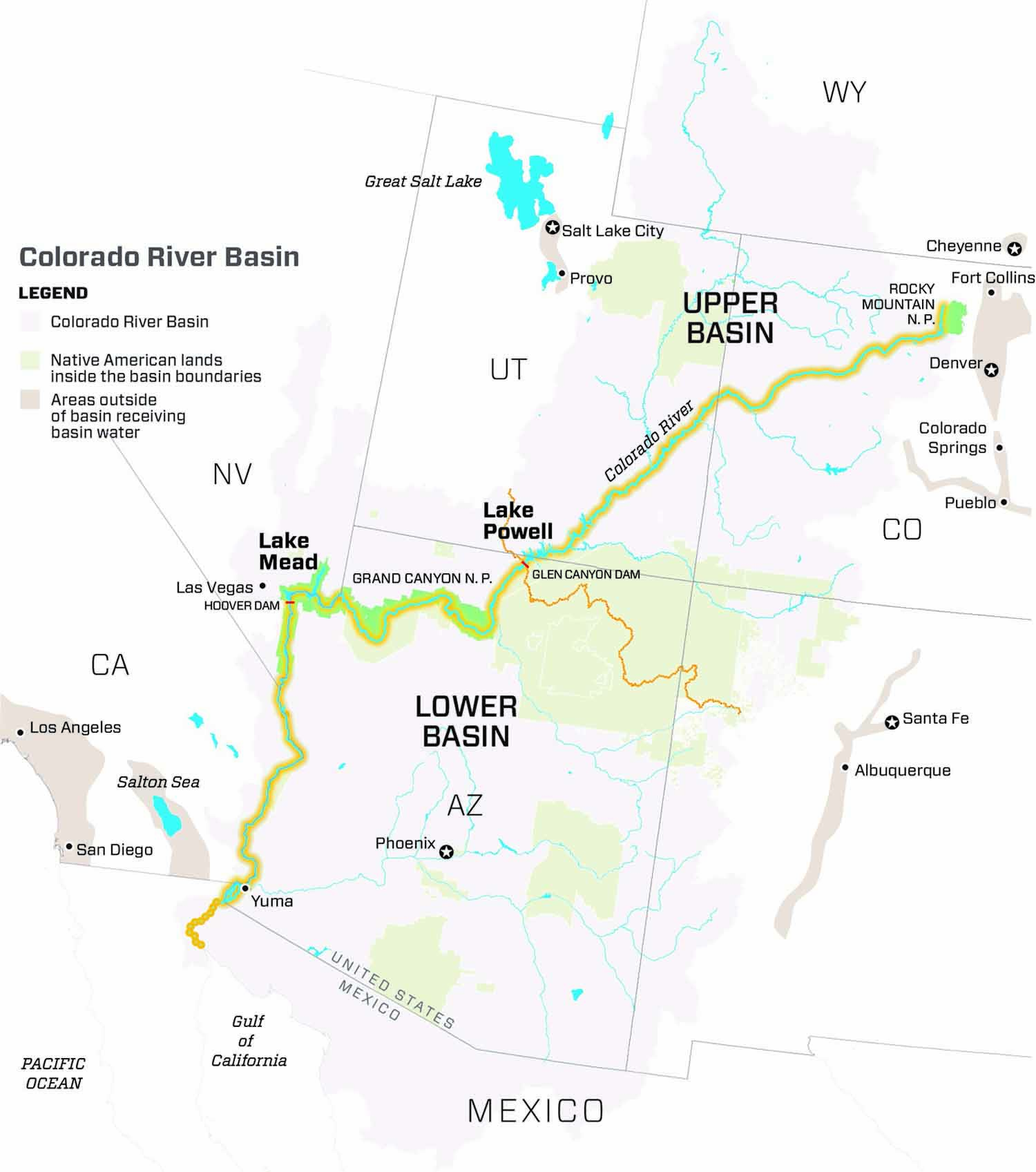

The Colorado River Basin, which is divided into two regions, includes seven states: Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming make up the Upper Basin, while Arizona, California and Nevada comprise the Lower Basin. Lake Powell serves as the largest water bank for the Upper Basin, while Lake Mead holds water for the Lower Basin states.

But as drought and climate change continue to sap the Colorado River, even the water in the Upper Basin’s high elevation storage ponds, namely Flaming Gorge, Blue Mesa and Navajo, isn’t enough to protect the larger system, and those kinds of releases can’t go on indefinitely, said Jim Prairie, a hydrologic engineer with Reclamation.

“We could release from Flaming Gorge maybe two more times,” Prairie said at a conference convened by the Colorado Water Congress last week.

And Blue Mesa and Navajo, now at less than 50% of capacity themselves, are considered too low to provide much, if any, additional relief.

It is analyses like these that prompted Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton in June to order the seven basin states to find ways to come up with 2 million to 4 million acre-feet of water next year, to inject into the reservoirs to keep them full enough to generate hydropower and supply water.

That means determining which water users and states are going to cut back use.

Tensions are rising as the federal government and the states continue to fail in their efforts to develop a concrete plan that will cut water use enough to come up with that 2 million to 4 million acre-feet.

“If we failed at anything in the [drought contingency planning done in 2019] it is that our vision was insufficiently dark,” said Wayne Pullan, director of Reclamation’s Upper Colorado Region.

As the freefall on the river continues, veteran federal hydrologists and engineers at Reclamation are scrambling to come up with new ways to forecast what is going to happen, using, among other tools, a stress test that is based on recent observed inflows, rather than models.

Hydrologists are also using data that excludes measurements from extremely wet years back in the 1980s, and focuses instead on the most recent dry periods.

Reclamation estimates that Powell will receive just 6.2 million acre-feet of water from the mountain snows in Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico in 2022, using its new forecasting models. That is far below the 9.6 million acre-foot average, a figure based on a 30-year average that includes extremely wet periods.

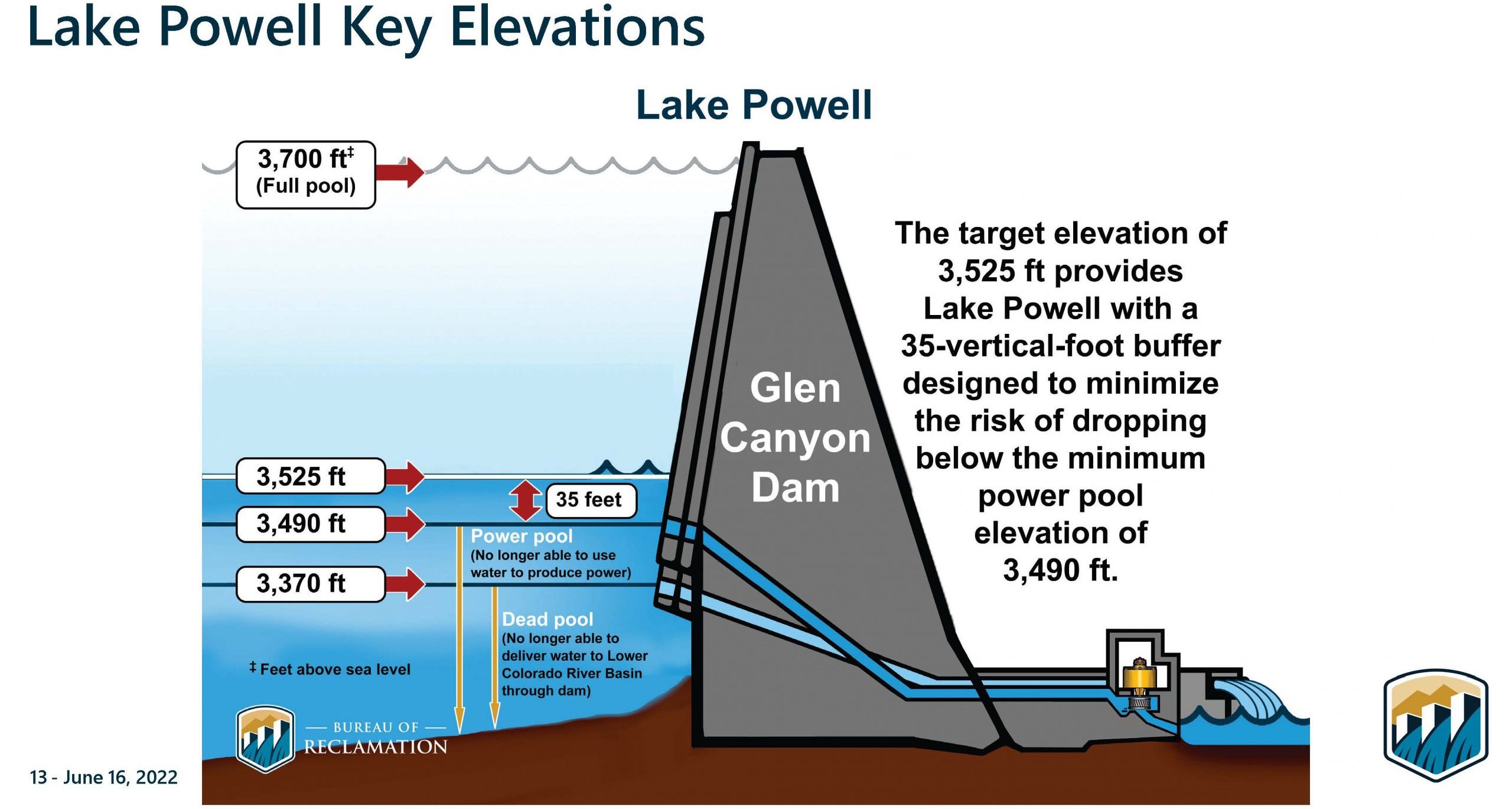

Right now, Powell stands at 3,533 feet, just 8 feet above the top of a buffer pool that must be maintained to keep the reservoir’s power turbines operating. Lake Mead is similarly low, with an elevation of 1,043.42.

Reclamation expects the reservoirs’ levels to continue dropping next year as well. “This could be where our hydrologies are going to stay,” Prairie said.

But it isn’t only the one-year outlook that is so troubling, Prairie said. It is the wildly varying temperature scenarios, low soil moisture levels, and shrinking snowpacks that are making it difficult to determine the best methods for keeping the giant river system, and Powell and Mead, from crashing.

Ironically, 2022 is shaping up to be slightly wetter than 2021, when inflow was just 3.5 million acre-feet, well below the 6.2 million acre-feet expected for this year.

Urging water users to move quickly to find ways to deliver and keep more water in the system, Prairie said, “Even if we have a good year next year, it is not going to save us.”

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.