By Maria Dolan

Editor’s note: This story is part of a nine-month investigation of drinking water contamination across the U.S. The series is supported by funding from the Park Foundation and Water Foundation. Read the launch story, “Thirsting for Solutions,” here and the other stories in the series here.

First, Crystal Stephens noticed the new, odd odor of her tap water. “It smelled either like bleach or fishy,” says the resident of Hannibal, Missouri. Then, when she showered, she developed a cough, sinus issues and dry skin.

“People called it ‘the crud,’” she says.

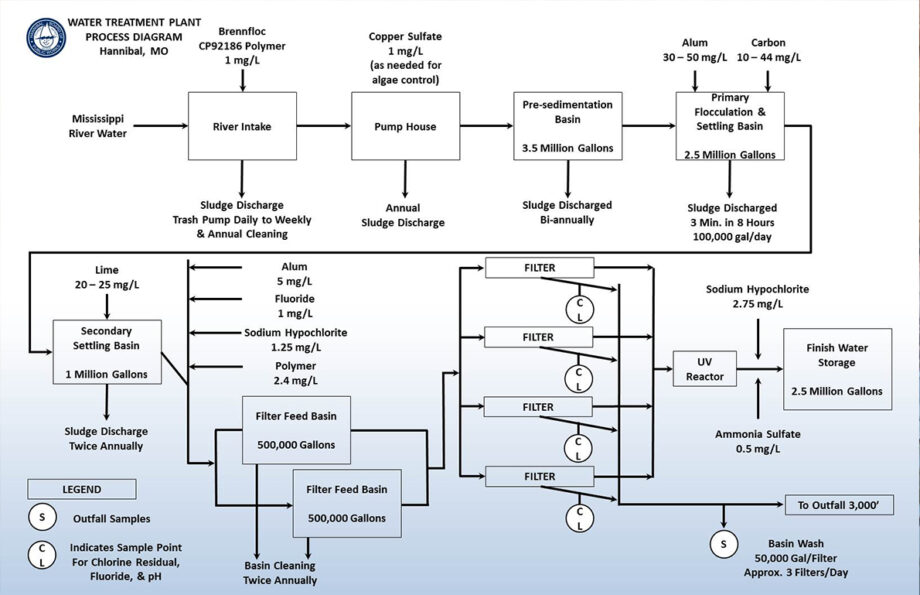

In late 2015, Stephens was one of many residents in Hannibal, a city of 17,000 people on the Mississippi River, who complained about the quality of the city’s drinking water. That was after the Hannibal Water Treatment Plant introduced ammonia to their chlorine disinfection system, a move that aimed to meet federally regulated standards by lowering levels of total trihalomethanes (TTHM). Trihalomethane is a disinfection by-product and known carcinogen.

The disinfectant created by the chlorine-ammonia mix, chloramine, was effective at eliminating trihalomethanes, and provided protection against waterborne diseases. However, the use of chloramine raised a new problem: As the new chemical interacted with organic materials in the water, it created more, unregulated disinfection by-products — which coincided with “the crud” that concerned Stephens and other people drinking the water in Hannibal.

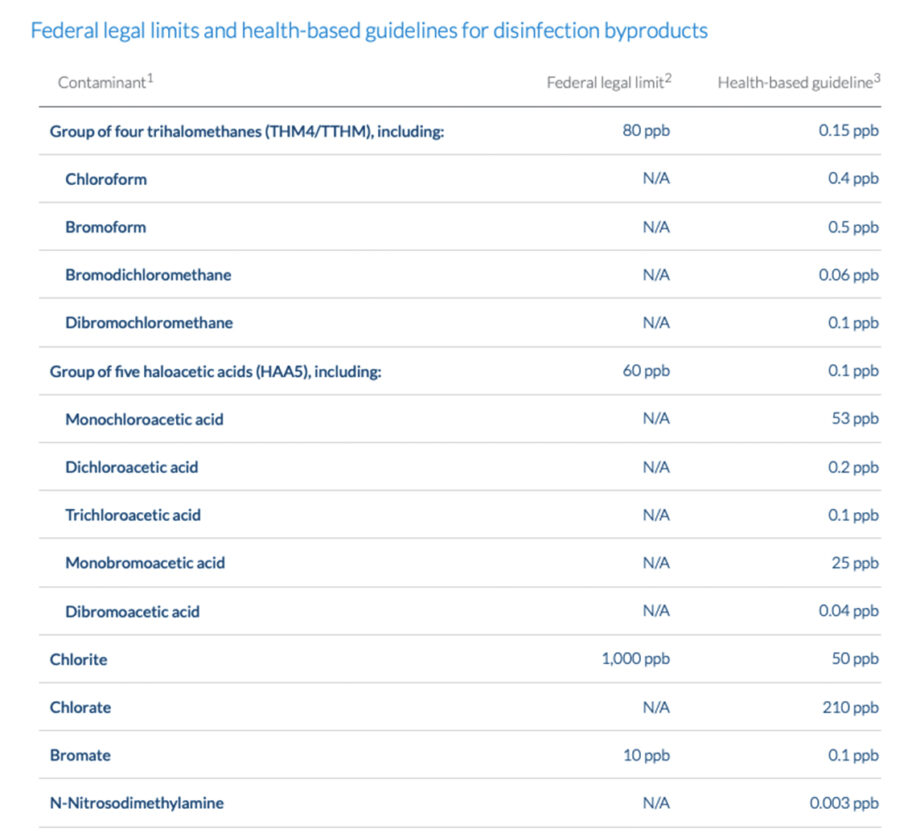

Hundreds of disinfection by-products have been found in treated drinking water across the U.S. since the 1970s, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) currently regulates a small number of those. The federal government also asserts that chloramines are safe at the levels they are consumed in treated water. But some researchers and activists have argued that emerging science is finding potential long-term hazards in newly identified disinfection by-products, and that regulations need tightening to protect the public.

Without such regulations, citizens in many communities around the country — including Tulsa, Oklahoma; Portland, Oregon; and Stockton, California — are questioning, and sometimes criticizing, the use of chloramines. In some instances, consumers worried about the safety of these chemicals have successfully pushed utilities to switch to other treatment options that can provide clean water, and remove disinfection by-products, without adding more chemicals.

That’s what happened in Hannibal, where, in late March, 2020 the city brought online a state-of-the-art water treatment system that uses granular activated carbon (GAC), a porous media made from high-carbon material such as wood, coal or coconut shells. This material can bind to and remove some chemicals and heavy metals from water. It’s “much like you would see inside of a Brita filter,” says Karen Marie Dietze, a water process engineer at the engineering firm Black & Veatch. “When water is filtered through the GAC media, dissolved organic compounds in the water are attracted to the surface of the GAC media and removed from the liquid stream.” Also similar to a Brita filter, the media requires periodic replacement.

Building the Hannibal facility cost US$10 million, and came about after a protracted battle between the city and some of its residents. Initial operational costs were budgeted at US$350,000 per year.

Complaints of Rashes, Breathing Problems and “Frankenwater”

Hannibal wasn’t the first city to make the switch after an upswell of negative public sentiment.

The pushback against chloramines often starts with consumers who report adverse effects from drinking or bathing in chloramine-treated tap water.

“People get rashes and people have breathing problems with chloramines,” says Randy Alstadt, administrator for the Poughkeepsie, New York, Water Treatment Facility. The city, which takes its water from the Hudson River, also tried using chloramines to lower their levels of disinfectant by-products and meet EPA regulations. It was the cheapest option offered by the engineers hired to consult on the project, says Alstadt.

But in 2016, he says, the city switched to a system that removes the contaminants using granular activated carbon, a change that came after controversy in the community over the use of chloramines. Alstadt says there were complaints, and even lost business, as one of the city’s wholesale customers labeled the Poughkeepsie product “Frankenwater” and elected to install their own well and treatment plant rather than remain with the water utility.

The Poughkeepsie water distribution system also experienced significant problems with corrosion when using the added chemical. “Chloramine is very corrosive and eats up rubber,” says Alstadt. “It eats gaskets.”

In some cases, that deterioration caused brown water to run from taps. “It looked like iced tea,” Alstadt recalls. The new system has turned things around, he says: “We’ve been very happy with what we did. It was the right thing to do.”

Battle in Hannibal

Hannibal, famous as the childhood hometown of author Mark Twain and the place that inspired the setting for The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, pipes its water from the Mississippi River, and had already experienced its share of water treatment woes before the struggle against chloramines ramped up in 2015. For several years, the city’s Water Treatment Plant exceeded federal, health-based standards for disinfectant by-products in drinking water, leading the city and Board of Public Works to settle a class-action lawsuit with four Hannibal residents, including Stephens, that alleged the board had knowingly provided sub-standard drinking water.

Under pressure to control disinfectant by-products from chlorine, Hannibal hired an engineering firm to present options for meeting compliance. From the available choices, the city chose chloramination to solve the problem. That decision became a hot-button issue in town as soon as customers received a notice from the Hannibal Board of Public Works announcing the plans to add chloramines to local drinking water. “It was really a fight,” says Hannibal resident Pat Berg Yapp, who, with her husband, owns The Belvedere Inn, a B&B in an 1859 mansion near downtown Hannibal’s historic district. Stephens and several other residents gathered to discuss the issue at a local coffee shop, and eventually formed a group, now called Concerned Citizens for Safe Drinking Water, to organize against the use of chloramines and instead advocate for the use of GAC. Water quality advocates Erin Brockovich and Robert Bowcock visited Hannibal, and, at a packed public meeting, spoke about the risks of chloramine by-products.

The Hannibal City Council soon declined to vote on a proposed ordinance, the Safe Drinking Water Chemical Use Reduction Act, which local citizens had brought to the council in a bid to halt the city’s use of chloramines for water treatment. After the council’s decision, chloramine opponents gathered enough signatures to put a proposition on the ballot that year to remove ammonia from municipal water treatment. That proposition passed in 2017, forcing the city to find an alternative.

Hannibal hired Black & Veatch to evaluate several methods for modifying the treatment process to reduce the formation of disinfection by-products without using ammonia. They tested enhanced coagulation, oxidation, adsorption technologies — including powdered activated carbon and granular activated carbon — and reverse osmosis. The decision to select GAC as the preferred approach was driven by its ability to effectively meet treatment goals, ease of implementation and operation, and ability to meet the city’s ordinance schedule. “Among the treatment alternatives evaluated, GAC adsorption was one of the more cost-effective approaches and would be able to reliably meet the treatment objectives under varying water quality conditions,” says Black & Veatch’s Dietze.

So far, “the system is performing as anticipated,” says Mathew Munzlinger, director of operations at the Hannibal Board of Public Works.

Yapp and her husband say they have noticed the change, both in the taste of their coffee and in the clarity of their drinking water. They once supplied bottled water to guests, and told them to avoid the city’s tap water. No longer. “I now tell people you can drink the water here,” says Yapp. “A year ago, I wouldn’t have told you that. Now it literally comes out of the faucet and it is as clear as a bell, and the taste is fabulous.”

For Hannibal, this also means water clear of disinfection by-products. Many other communities questioning the use of these chemicals are trying to decide if this matters to them, as the EPA reviews its rules on disinfection by-products, and experts continue to weigh in.

Editor’s note: The Environmental Working Group (EWG) is a collaborator on this reporting project.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.