A cold, wet heart beats delicately in the palms of my hands. A flick of the fish’s tail subtly curves the arc of its glossy body with the grace of a dancer. Mark Cantrell, a fisheries biologist with US Fish and Wildlife, heckles me. “If you love the chub, then you gotta kiss ’im!” I lift the humpback chub to eye level before pressing its body to my lips. A thin film from the fish kiss rests on my mouth. I don’t wipe it off as I release the chub back into the muddy water. “That was the thrill of that chub’s life,” Cantrell chuckles.

Water Desk Grantee Publication

This story was supported by the Water Desk’s grants program.

It’s a bold move to kiss a species I just met, but I know love when I feel it.

The humpback chub is native to the Colorado River corridor, where it has lived for 5 million years, and exists nowhere else on Earth. It is named for a signature hump overhanging a sleek pearlescent body with pale vermillion fins. Its eyes are adapted to see through muddy waters, and its gills and mouth contain protective flaps that filter out sediment. Come spawning season in spring, the humpback chub’s fins burn a bright shade of red, the same shade as the 340-million-year-old Redwall limestone formation towering above its home waters.

The humpback chub has the distinction of having been included on the very first endangered species list, put there by development and clumsy habitat manipulation on the Colorado River. During the Great Depression, for example, sportfish like trout were introduced to the river because they were considered better eating than the bony native fish. The new arrivals swiftly devastated the chub.

In 1962, the Green River Project tried to further control native fish—considered “trash fish” by some—by releasing 20,000 gallons of rotenone into 500 miles of river. The poison had the desired effect on humpback chub, Colorado pikeminnow, bluehead sucker, and humpback sucker. The native Colorado River cutthroat trout was nearly driven extinct from this one incident.

After the completion of Glen Canyon Dam in 1963, colder water released downstream into the Grand Canyon made the native fish susceptible to non-native cold-water predators like rainbow and brown trout. The cooler waters also inhibited the humpback chub’s ability to spawn in most areas of the river. The dam drastically reduced population numbers of all native fish in the Grand Canyon and earned the humpback chub a spot on the endangered species list. The fish’s fortresses were now limited to tributaries with warmer water that retained the Colorado’s pre-dam characteristics of flooding and muddiness.

Efforts were made in the 1990s to recover chub populations, but experimental high-water releases from Glen Canyon Dam to mimic natural floodwaters were largely unsuccessful. Then in 2009, the National Park Service hired fisheries biologist Brian Healey to start a native fish conservation program in the Grand Canyon, which focused on efforts to control the brown and rainbow trout. It also involved translocating humpback chub from the Little Colorado River—home to a self-sustaining population since before and after the dam was constructed—to new tributaries like Havasu Creek. The goal was to establish new chub populations in the Grand Canyon and increase their resilience, an ongoing effort that’s bolstered by the 1,000 humpback chub incubated annually at the Dexter National Fish Hatchery in New Mexico.

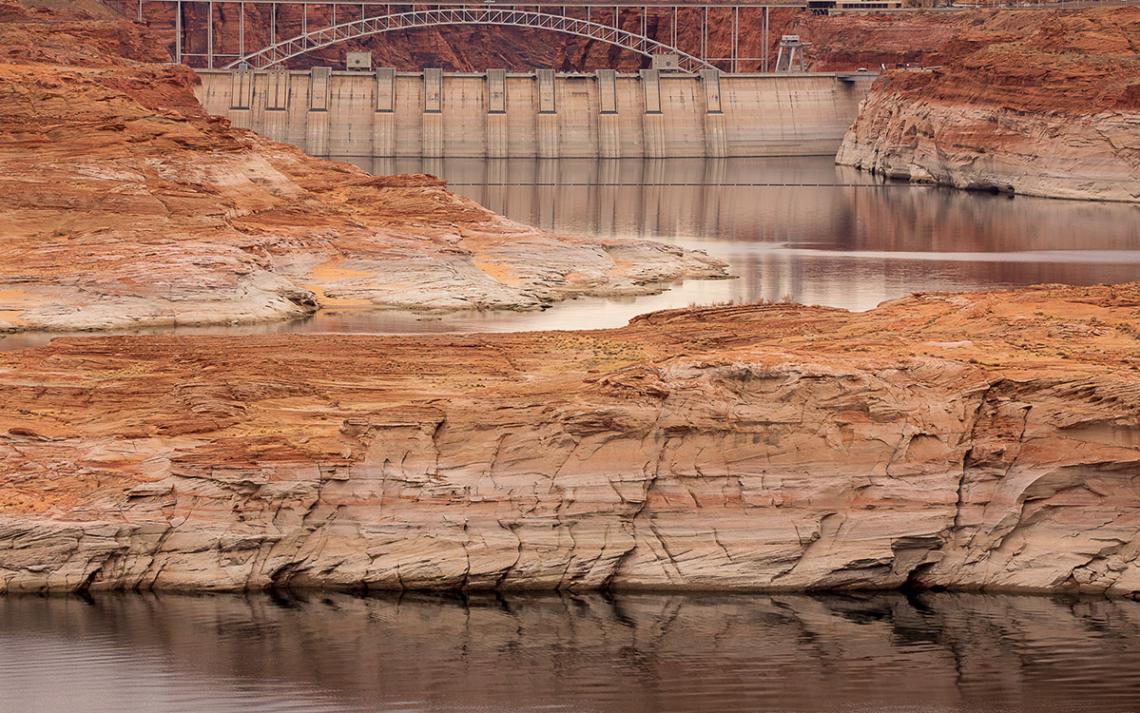

The US Geological Survey (USGS) estimates that since 2000, adult chub spawning populations in the Little Colorado River have grown from 4,000 to 10,000. The chub have also started spawning farther downriver in the mainstem Colorado. In 2021, the species was downlisted to “threatened,” partly because of recovery efforts but also because of record-low water levels in Lake Powell, the reservoir impounded by Glen Canyon Dam, which releases water downstream into the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. Typically, this water is cold, drawn from deep below the reservoir’s surface. But with drought and over-allocation leaving the lake far below maximum capacity, warmer surface water now passes through the dam’s penstocks. This fall, it was up to 70°F, the warmest in 50 years—just how humpback chub like it for spawning.

Unfortunately, the warmer water is also ideal for predatory, non-native smallmouth bass and green sunfish. Their meal of choice: humpback chub.

Seventy-six miles down from Glen Canyon Dam is the confluence of the Little Colorado River with the mainstem Colorado River. The 107-mile-long tributary is known for its stunning turquoise-blue water created from dissolved calcium carbonate. Its warmth and wild undammed flows make it a refuge for the humpback chub. Today, the Little Colorado is a ruddy brown color in the wake of a major flood that churned up sediments. I am hiking along the willow and tamarisk-lined riverbank with US Fish and Wildlife fisheries biologists Cantrell and Rudy Van Haverbeke, who are checking survey nets for humpback chub. The fish counts are predictably low due to the flood, which sent many of the chub scurrying into the calmer waters of the mainstem Colorado.

Each humpback chub caught is tagged with a tiny microchip that allows scientists to track its growth, location, and migration. Van Haverbeke pulls up a net from the river with two chub. He lifts the first squirming fish gingerly from the net and scans its tag, then places it on a wooden measuring board. This male fish, despite having bite marks from a merganser across its body, has managed to grow from 156 millimeters to 230 since last year. The next chub is 375 millimeters. “Mambo Chub,” mutters Van Haverbeke in a hushed but stoked tone. Most of a chub’s growth occurs in the first three to five years of life, he explains, before its biological energy is diverted to reproduction. Young humpback chub are the most susceptible to predatory fish, making these growth spurts essential.

Back at camp—a sandy delta with a stately mesquite tree as its centerpiece—last light disappears behind the 3,000-foot high canyon walls at 4:30 p.m. Van Haverbeke is unwinding by tuning his guitar. It’s Halloween and he’s dressed in a black blazer, with no shirt, ripped pants, a bandanna hovering over his gray ponytail, and black eye makeup—Keith Richards is on tour in the Grand Canyon tonight. I pull up a chair next to him. A fake black mustache, bestowed upon me by the crew, wrinkles below my nose when I begin our interview. “So, Randy, I mean Keith, what is your outlook about the impending standoff between the smallmouth bass and the humpback chub?”

He shrugs. “The thing about the smallmouth bass is that we don’t know how they will respond to the turbidity of the water in the Lower Colorado and the frequent flood and disturbance events,” he says. “This is a stronghold for the chub, and it is often inhospitable to non-native fish that have not evolved to persist in these extreme conditions.” Van Haverbeke has worked with humpback chub populations here for over 30 years. After spending decades of his life below the canyon rim and having witnessed their revival firsthand, he remains optimistic.

When it comes to the main stem of the river, though, where the smallmouth bass and humpback chub are colliding, it’s a different matter. “It’s a cluster,” he says.

Surprisingly, humpback chub in the Grand Canyon have fared well because of the Glen Canyon Dam. “It’s the dams that have kept our native Colorado River fish from going extinct,” explains USGS fisheries biologist David Ward. “If the dams weren’t there, we already would have lost them all because the invasive warm-water fish would have come in and established and wiped them out. The dams and the cold water basically bought us 30 to 50 years. And now we’re having to deal with the crux of this problem.”

Warm water passing through Glen Canyon Dam and raising temperatures in the Colorado River creates favorable spawning conditions for the humpback chub and makes them more likely to venture out from their favored tributaries into the main stem of the river. But while the temperature change lessens their risk of an encounter with rainbow and brown trout, it heightens their peril from smallmouth bass and green sunfish.

In July 2022, the National Park Service registered the presence of smallmouth bass in a small backwater slough three miles below Glen Canyon Dam. Green sunfish, which were already a management concern, were also present. Healey is blunt: “We expect that if smallmouth bass and other predators become established, it could be a point of no return for humpback chub and other native fishes in Grand Canyon.”

In response, the NPS led a multiagency emergency effort during September 2022 to prevent the non-native fish from traveling downstream. A team of 15 people from multiple federal and state agencies deployed the pesticide rotenone to attempt to remove the invasive fish from the slough.

Unlike the massive quantities of rotenone used in the Green River in 1962, today’s treatment protocols involve heavily monitored, EPA-approved methods that are determined safe for wildlife and humans. The slough was closed to the public during the treatment, and an impermeable fabric barrier was set up to minimize the treated water mixing with the main river channel. Potassium permanganate, a chemical used to purify drinking water, was distributed into the river as a neutralizer. The Bureau of Reclamation also strategically released water from Glen Canyon Dam at a flow of 9,300 cubic feet per second during the procedure in hopes that any rotenone that did make it out of the slough would be diluted to a level that would not affect humans or wildlife. Native fish, including the humpback chub, were considered safe as they are not typically found in the colder water just below the dam.

Based upon visual surveys from the treatment, NPS staff reported that they were “fairly certain we removed all the smallmouth bass and green sunfish from the treatment area.” But David Ward, who was involved with the rotenone treatment, believes that the relatively small number of fish caught indicates that the effort was possibly made too late. He hypothesizes that a large number of smallmouth bass already matured and moved downstream from the slough. “It kind of left us with more questions than answers,” he says. “Was it that there weren’t very many smallmouth bass there to begin with, or was it that they already left?”

In late fall, NPS also employed a manual method to remove non-native fish known as “electro fishing.” A generator on a fishing boat puts a pulsed DC current into the water that takes the path of least resistance and concentrates through nearby fish, because their bodily tissues are saltier than the surrounding water. It causes their muscles to temporarily spasm and tighten, causing them to lose equilibrium and flip onto their backs. The scientists then net the fish and euthanize them with carbon dioxide.

Not everyone agrees with lethal efforts to remove non-native fish. The Pueblo of Zuni objects to taking the life of fish in Glen and Grand Canyon without significant justification. To the Zuni, native fish have been a linkage to their relatives since time immemorial. But they value the life of all sentient beings, including non-native fish. “Grand Canyon is a place of emergence and migration, where life was given within the body of the living water,” explains Zuni governor-elect Arden Kucate. “Before dams were put into place, these areas of life were in their natural state—the fish, the plants, the water, everything within that whole corridor of the Colorado River. And so, for us as Zuni people, our emergence and way of life gave us insight on how we needed to honor every living form of life down to the lowliest creature.”

The use of lethal methods to remove fish in Glen Canyon this fall was done despite an official protest from the Zuni. In a September 9 letter to Michele Kerns, superintendent of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, former Zuni governor Val Panteah Sr. said that using rotenone in the river would cause adverse effects to values that Zuni have in the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River. “These negative effects will profoundly and adversely impact the well-being (psychologically, emotionally, spiritually, and materially) of the Zuni community,” he wrote.

In their statement, Zuni reminded NPS of a 2019 agreement regarding the management of non-native aquatic species within Grand Canyon National Park and Glen Canyon NRA. That agreement acknowledges that the Pueblo of Zuni views all fish, native and non-native, in the Grand Canyon as sacred. It recognizes the negative effects of lethal fish management actions on the Zuni community and requires further consultation with Zuni about the use of such methods. Nevertheless, the National Park Service proceeded with the rotenone treatment last fall without further dialogue with Zuni.

Kurt E. Dongoske, Zuni’s tribal historic preservation officer, cites the NPS’s use of rotenone as part of “continuing efforts, intentionally or not, to disenfranchise Zuni and other Tribes that are participating in the Glen Canyon Adaptive Management Plan.” (Dongoske notes he was not speaking for the Zuni Tribe but from his own perspective.) Even the terminology used to describe fish management, he says, like “invasive, predatory, and non-native,” is problematic. “Those fish don’t realize they’re in a park; they don’t realize that these humans have these management objectives; the fish are just being fish. Trying to vilify some fish because they’re upsetting your management objective for me is sort of quixotic.” For Zuni, the issue of fish management goes much deeper than the arrival of non-native fish but to a century of colonization and human manipulation of the environment. Both the introduction of non-native fish and the construction of Glen Canyon Dam were done without the consultation and agreement of Zuni and other tribes. For that matter, Grand Canyon National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area are on land directly stolen land from Indigenous people. Even the knowledge and use of rotenone by western scientists and land managers is derived from Indigenous people in the Amazon who used it for fishing.

Neither rotenone nor electro fishing are likely to significantly impede the growth of smallmouth bass or green sunfish populations. Electro fishing is typically used for fish monitoring and sampling; Ward says that there are very few studies that show it is effective for control of fish populations. In the upper Colorado River basin, despite $2 million spent annually to suppress non-native predatory fish to protect native fish, the humpback chub has been extirpated—meaning a local extinction from two-thirds of its historic habitat.

Dongoske believes that fish management needs to honor Indigenous perspectives equally with western science and federal land management. The Zuni Tribe has suggested nets and barriers as a culturally acceptable method to protect and manage fish in the Colorado River system. Ward favors a proactive solution that has the potential to embrace the ideals of all parties, by protecting the humpback chub without killing other species of fish. “The only solution is to create environments where native fish and non-native fish are separated,” he says. “My recommendation is to go into key tributaries and build small barriers with selective fish passage that allow the humpback chub to move between their tributary refuges and the main stem, but prevent new fish from swimming upstream.” The reentry fee is a momentary stop in a holding area where a monitoring scientist will grant upstream passage to a humpback chub while returning non-native fish to the main channel. Ward asserts that barriers have proven effective in the past.

Of course, the fact that the humpback chub need an official gatekeeper for their community is a testament to how western development has irrevocably altered nature. In my conversation with Governor Kucate and Dongoske, both men discussed how Zuni people view themselves as part of nature, not outside of it. Dongoske asserted that the Park Service, and most Western scientists, see humans as separate from nature, and see humans as being able to control nature, “and that’s what they’re trying to do in the Grand Canyon. They’re trying to control the behavior of sentient beings that are in the water.”

Looming over all is the future of the antiquated Glen Canyon Dam. Low water level projections for 2023 suggest that the warmer water passing through the dam is here to stay. But if the reservoir drops below an elevation of 3,490 feet, the dam will not be able to generate electricity. Another 120 feet beyond that and the Bureau of Reclamation will not be able to release water into the Grand Canyon at all, causing an ecological disaster for all species that depend on the Colorado River. The future of the Colorado River, and with it, the humpback chub, ultimately depends on how Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell are managed by the Bureau of Reclamation, Colorado River Basin states, tribes, and stakeholders in the coming years. Perhaps the 5-million-year-old humpback chub should, along with Indigenous people who have resided here since time immemorial, be granted the most senior water rights of all.

In the morning, warm orange light filters down into the canyon. The USFW crew sips coffee and goes about a quiet morning routine until the whirring noise of helicopter propellers fills the air. I walk out to the shoreline and look up. A bucket is being hauled below the red aircraft—filled with baby humpback chub. Their destination is further upstream in the Lower Colorado. The goal is to keep the juvenile fish far away from the main stem of the Colorado River so that they don’t venture into the prime territory of predatory fish, including the smallmouth bass. The humpback chub, who have persisted in such a uniquely challenging environment for millions of years, now live in a wild and remote assisted living community. And they need to be airlifted to safety in hopes that they will survive until we figure out new ways to protect them. With his neck craned up at the helicopter, Cantrell smiles. “It’s amazing how these fish just keep chubbin’ along.”

This story was made possible with funding from The Water Desk, an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. It was launched in 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundations with a mission to increase the volume, depth, and power of journalism connected to Western water issues.

Morgan Sjogren is a freelance writer based mostly in the wilds of the Colorado Plateau. She is the author of a forthcoming book, Path of Light: A Walk Through Colliding Legacies of Glen Canyon, which retraces the 1920s expeditions led by Charles L. Bernheimer into the heart of Glen Canyon (Torrey House Press). Sjogren’s Colorado River journalism is supported by a grant from The Water Desk. Follow her on Instagram @running_bum_.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.