A campaign to protect one of the last free-flowing rivers in Colorado is moving forward, but some proponents say not enough progress has been made over the past year.

Last spring a handful of advocates led by Pitkin County revived an effort to secure a federal Wild & Scenic designation, which would protect the upper Crystal River from future development, dams and diversions. A year into the effort, some say a planned stakeholder process is moving too slowly, while others say a designation can’t be rushed and must be approached carefully and inclusively.

The different philosophies underscore a rift between those who say a cautious and thorough multi-year approach is what’s needed to ensure success and those who say mounting threats to the river, driven by the climate crisis, demand bold and immediate action.

“That difference of opinion concerns me a great deal,” said Kate Hudson, Crystal River Valley resident and western U.S coordinator for Waterkeeper Alliance. “We are at an existential moment both in terms of water and climate and our congressional balance of power that requires we at least try and do this faster. We should at least try to move this as quickly as possible.”

In 2021 Pitkin County Healthy Rivers granted $35,000 to Carbondale-based environmental conservation group Wilderness Workshop to start up a public outreach and education campaign, with the goal of laying a foundation of grassroots support for the effort. The organization has built a website, held events and collected about 1,000 signatures on a petition supporting the designation. The next step will be working with Pitkin County to hire a facilitator for a formal stakeholder process.

At the June Healthy Rivers board meeting, Wilderness Workshop’s Wild & Scenic campaign manager Michael Gorman gave a presentation about progress so far. Board member Wendy Huber asked about the timeline and whether the process should be moving faster. Gorman said a designation could take several more years.

“I’m feeling a little urgency,” she said. “To sort of dilly dally seems to be losing opportunities.”

Grant Stevens, communications director for Wilderness Workshop, said that while he understands the community’s urgency, it’s important to develop a proposal that Colorado’s congressional representatives can get behind. A designation must be approved by Congress and advocates have been in contact with representatives from Sens. Michael Bennet and John Hickenlooper’s offices.

“We want to make sure we have something that a federal elected official will support, and we need to make sure we go through a community-driven process to get to that point,” Stevens said. “We don’t want to rush that.”

Designation details

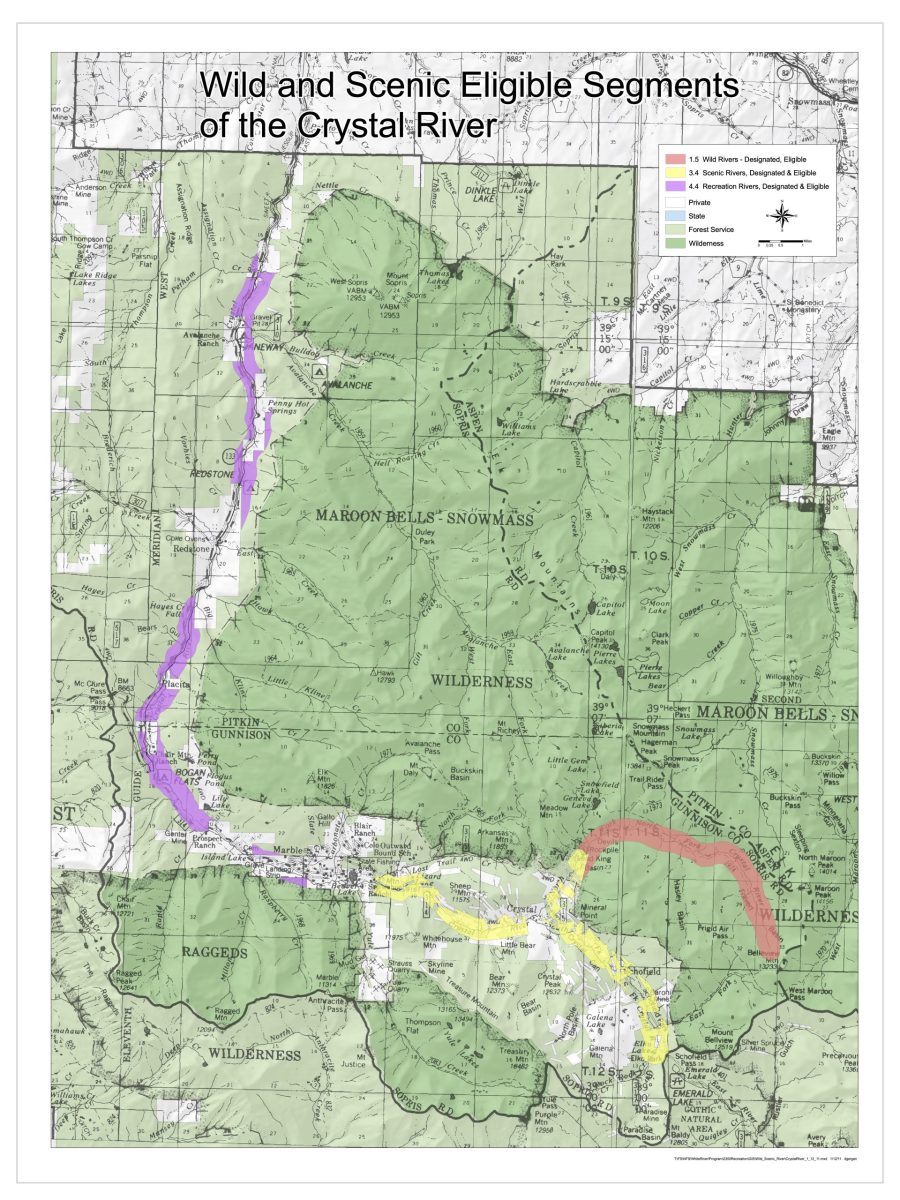

The U.S. Forest Service first determined in the 1980s that the Crystal River was eligible for designation under the Wild & Scenic River Act, which seeks to preserve rivers with outstandingly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic and cultural values in a free-flowing condition. There are three categories under a designation: wild, which are sections that are inaccessible by trail, with shorelines that are primitive; scenic, with shorelines that are largely undeveloped, but are accessible by roads in some places; and recreational, which are readily accessible by road or railroad and have development along the shoreline.

The potential proposal for the Crystal includes all three types of designation: wild in the upper reaches of the river’s wilderness headwaters, scenic in the middle stretches and recreational from the town of Marble to the Sweet Jessup canal headgate. Each river with a Wild & Scenic designation has unique legislation written for it that can be customized to address local stakeholders’ values and concerns.

Despite its renowned river rafting, fishing and scenic beauty, which contribute to the recreation-based economy of many Western Slope communities, Colorado has just 76 miles of one river — the Cache La Poudre — designated as Wild & Scenic. This underscores the difficulty of trying to preserve free-flowing streams, especially in a water-scarce region where some would like to see rivers remain available for future water development.

Stakeholder participation

Since the Crystal flows through Gunnison County and the town of Marble, advocates say getting those residents and elected representatives on board will be key to moving the effort forward. A first attempt at a Wild & Scenic designation, which sought to prevent the possibility of a future dam and reservoir project, couldn’t get buy-in from some Marble residents or Gunnison County. Advocates shelved the discussion in 2016 with the election of President Donald Trump. This time around, they hope to secure at least the participation if not the support of past opponents.

Marble Town Administrator Ron Leach acknowledged there is still a lot of work to be done as far as gauging public sentiment and building awareness.

Leach has been heavily involved in the town’s multi-year process to address overcrowding on the Lead King loop, a popular off-highway vehicle route near Marble. He said when it comes to these things, slow and methodical is the right strategy and that town officials are totally supportive of the Wild & Scenic stakeholders group, in which he participates as the Marble representative.

“The more process, the better the product,” Leach said. “I’ve learned that the hard way. Take it easy and make sure it’s right.”

Gunnison County Commissioner Roland Mason agreed. He said more conversations need to happen before he could say whether Gunnison County would support a designation.

“I appreciate the fact that they are not trying to rush the timeline,” Mason said. “From my perspective it’s moving at a little bit of a slow pace because of trying to get everyone on board but at the same time, it’s kind of necessary.”

But supporters may never get everyone on board. Larry Darien, who owns a ranch on County Road 3 that borders the river, was one of the early opponents to the designation and still remains opposed to Wild & Scenic because of its potential effect on private property.

While the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act does give the federal government the ability to acquire private land, there are many restrictions on those abilities. Condemnation is a tool that is rarely used, according to a Q&A document compiled by the Interagency Wild and Scenic Rivers Coordinating Council.

“I’m not in favor of a dam on the Crystal River and I’m not in favor of water being taken out and sent someplace else and I’m not in favor of Wild & Scenic designation,” he said. “There are other ways we can manage this besides Wild & Scenic and I think that’s the way we need to go instead of getting the federal government involved.”

The alternate route Darien is referring to is a collaboratively created alternative management plan on the Upper Colorado River, which offers some of the same protections as Wild & Scenic, but still allows for some water development.

Advocates will have to decide whether total consensus is a realistic goal and if they should move forward even though some opposition remains.

Threats to the Crystal?

While there may be a general feeling of worry about drought and falling reservoir levels in the Colorado River basin overall, it’s unclear what — if any — specific, imminent threats there are to the upper Crystal River. In 2012, conservation group American Rivers deemed the Crystal one of the top 10 most endangered rivers. This was spurred by plans, which have since been scrapped, from the Colorado River Water Conservation District and the West Divide Conservation District to preserve water rights tied to reservoirs near Redstone.

Still, in a place where much of the state’s headwaters are taken across the Continental Divide to thirsty Front Range cities, Wild & Scenic proponents say it could happen on the Crystal, even if those threats are currently hypothetical. Many of Colorado’s rivers have been overly tapped, but there’s still water left to develop on the Crystal.

“To me, the greatest threat to the Crystal isn’t so much the storage facility, it’s that there’s still water in the Crystal,” said Pitkin County Attorney John Ely. “The biggest risk to the Crystal is just taking water out of the drainage. That’s why I think the (Wild & Scenic) effort is still worth doing.”

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.