By Gary Pitzer

Managing water resources in the Colorado River Basin is not for the timid or those unaccustomed to big challenges. Careers are devoted to responding to all the demands put upon the river: water supply, hydropower, recreation and environmental protection.

All of this while the Basin endures a seemingly endless drought and forecasts of increasing dryness in the future.

For more than 30 years, Terry Fulp, director of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Basin Region, has been in the thick of it, applying his knowledge, expertise and calm demeanor to inform and broker key decisions that have helped stabilize the Southwest’s major water artery. The centerpiece of that effort was the landmark 2007 Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the river’s two major reservoirs. Fulp was instrumental in developing the modeling tool called RiverWare in the 1990s that has been used to build the data foundation for most of the key operational decisions on the river during the past 20 years.

“What really is the key to success are relationships. You can’t really work closely with folks and on very complex and contentious issues if you don’t know about each other and respect each other.”

~Terry Fulp, director of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Basin Region

Even with the 2007 agreement, worsening drought and declining reservoir levels pushed the seven Basin states — Arizona, California, Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — into urgent but protracted negotiations. The result was unprecedented Drought Contingency Plans last year for the Upper and Lower Basins that included participation by Mexico, a development founded on Mexico’s recent ability to store some of its water in Lake Mead.

Fulp has played an integral part in all of these decisions. As 2020 nears completion, so does Fulp’s career with Reclamation. He’s retiring after 31 years with the agency’s Boulder City, Nevada, office, which oversees the last 688 miles of the river’s path in the United States, including Hoover Dam to the Mexican Border. In an interview with Western Water, he talked about his accomplishments in a leadership role and the challenges that await the many Colorado River water users as they begin the arduous task of negotiating a new operating agreement for the Colorado River to replace the current one that expires in 2026.

WW: What’s been your proudest accomplishment as Regional Director?

FULP: The biggest one probably is our leadership in the collaborative approach that we have shown works so well in the Basin over the last 20 years, starting with the Interim Surplus Guidelines all the way through the Drought Contingency Plans, and Mexico’s big part of that. Forging a really close relationship with our colleagues in Mexico has been key to that program’s success. I think we’ve been able to accomplish some really important things.

WW: Are there examples that come to mind where people made a breakthrough in their relationships?

FULP: Definitely. Starting all the way back to what was called the California 4.4 Plan in 2003, that was huge. The Multi-Species Conservation Program also comes to mind. It’s still very unique and very successful in all of the environmental type of programs within this country and even within the world… And then of course the Interim Guidelines in 2007, the flagship agreement between the Upper and Lower Basin on the coordinated operation of the two big reservoirs. And, if I can add one more, our relationship with our Mexican partners was unforeseen 15 to 20 years ago.

These agreements are still working well but there have been hiccups and the main hiccup is the drought. It became more severe and drove the need for the Drought Contingency Plans that were signed on May 20th of last year. We worked over five years on that. These things are complex and sometimes they take a really long time. Living in it felt like it was long to me for sure and probably everybody else who was so involved in it. It just shows the complexity with all the different interests and that the way you get through that is really being collaborative – building relationships amongst all of us and then being able to really talk about the serious issues and find compromises.

WW: This is an important time, as the renegotiations of the 2007 Interim Operating Guidelines will soon begin in earnest. What are some of the major challenges that all the parties will have to overcome?

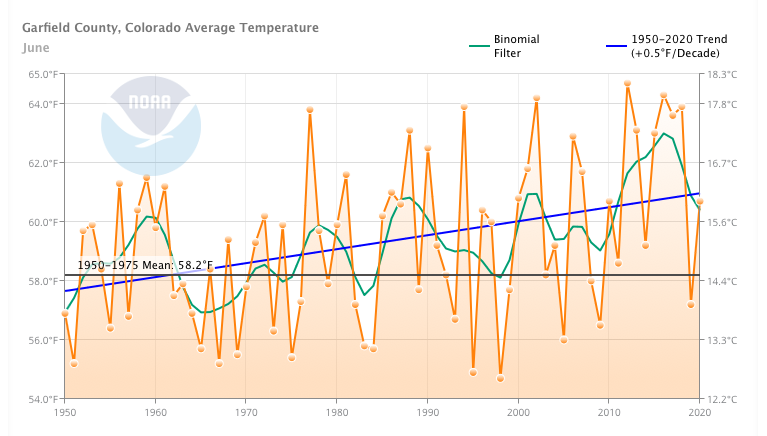

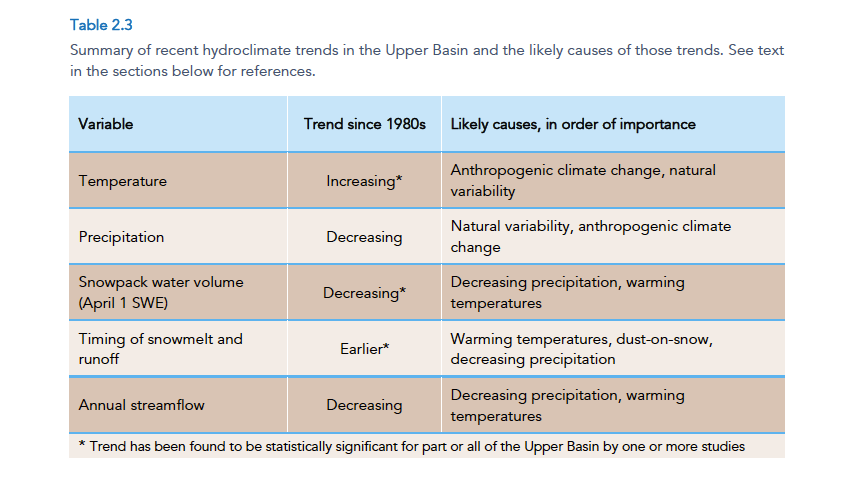

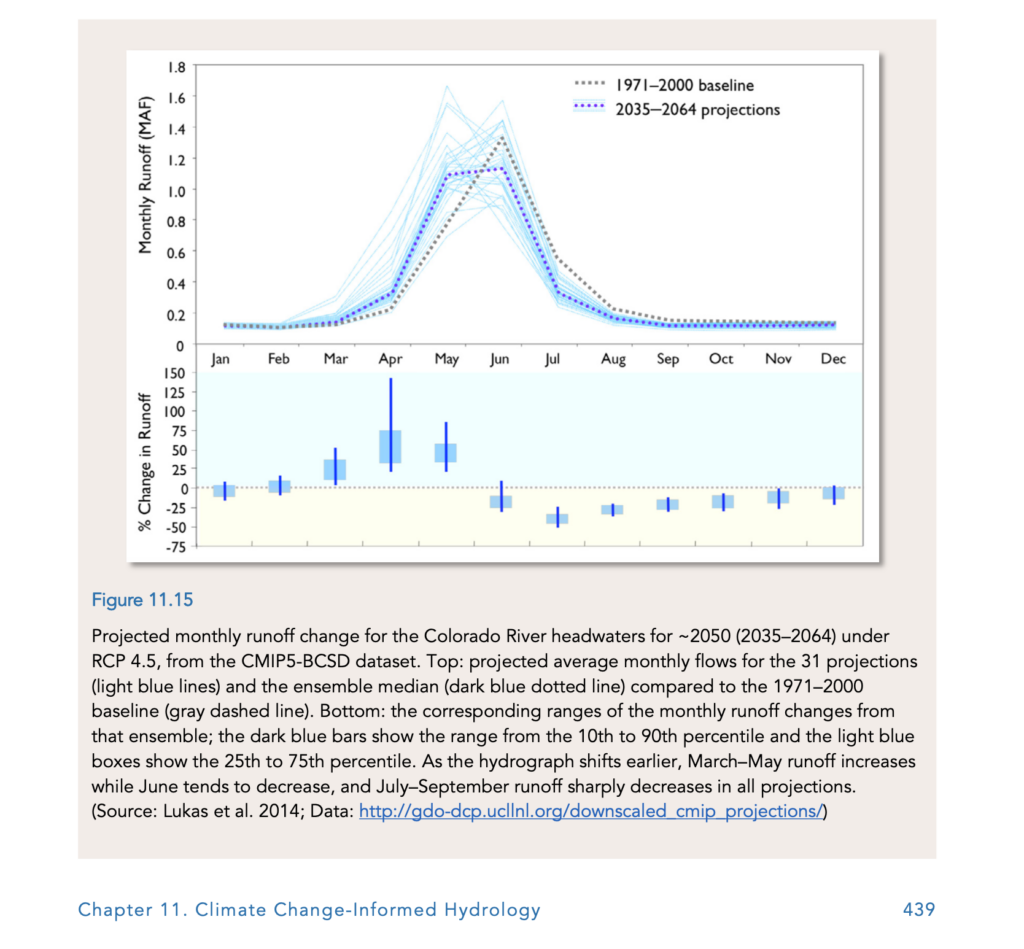

FULP: The foremost one in my mind is the changing hydroclimate. Certainly, we know from the very solid research that is now almost 10 years old, just the warming of the planet… explains 8 percent to 10 percent of the decline in water flow due to increased evaporation and evapotranspiration. So that’s paramount in terms of what we’ve got to deal with. … It brings up issues between the Upper and Lower Basin, primarily that the Lower Basin is at full development and has been for the better part of 20 years and the Upper Basin isn’t. With decreasing water supply, that’s going to be a really thorny issue to figure out.

What we know from other river basins and even this one, is the last place you want to be is in a courtroom letting a court decide the best way to operate. That belief is still consistent throughout the Basin. We don’t want to end up there.

WW: As water users, including tribes, seek to fully develop their water right allocations in a tightening system, how can the spirit of collaboration and cooperation be maintained?

FULP: You brought up the tribal issue and I really view them as an integral part of the Basin family. And so, when I talk about the Lower Basin that I’m in and the people that need to be involved in this collaborative effort, obviously the tribes are key in that. And they also haven’t grown into their full potential in terms of water use.

If I could relive this, I would have had a stronger focus on not just relationships with the tribal community, but also helping them build the capacity within their individual tribes to more effectively participate in these complex discussions. We are well on that path now and lots of folks are working hard and I feel very optimistic that we are not just on the right path, but we’ve made significant accomplishments in that area and it will just continue to improve.

What really is the key to success are relationships. You can’t really work closely with folks and on very complex and contentious issues if you don’t know about each other and respect each other.

I know it sounds simple. Of course, it’s not, in fact. It takes a lot of work just like the technical work is really important and the policy work, but [relationships] are equally as important, maybe more important.

WW: A host of experts have outlined scenarios of drying Basin conditions fueled by climate change. What has to be done now to get ahead of this?

FULP: We’ll know more in 10 years than we do today, more about what’s really going on with Mother Nature. We won’t have all the answers on how to deal with that and there still will be great uncertainty to our future. I think in 10 years we will have put other mechanisms in place to mitigate those impacts, but I don’t think we’ll have it all solved by any means. We don’t even fully understand yet what we’re facing.

WW: Is there room for getting even more innovative with the U.S.-Mexico relationship as far as how water is shared?

FULP: I think so. We do these things in increments. I love the term ‘pilot.’ I think the best way to get your experience initially and prove a concept is to do a program that is of finite duration with very specific, agreed-to goals and accomplishments. That’s the way you prove success and then you’re able to go forward to that next step.

Our agreement originally with Mexico to store water in U.S. reservoirs, because of that earthquake damage [in 2010] where they could not use their water during that period of time, was a huge breakthrough. It did have a finite term but because of that success we were able to build that concept into Minute 319 and expand upon it. And then Minute 323 went another step and extended those concepts and even included a drought plan. The door was then opened to much bigger projects to be co-funded by Mexico and the U.S. As an example, we have a work group looking at big picture desalination that the countries could share both the costs and benefits of that.

WW: You once told the story of how you were asked early in your career what the bumper sticker message would be for Colorado River Basin hydrology, and your answer was “Lake Mead Will Go Down.” Looking at the challenges ahead in the Basin, what would that bumper sticker message be today?

FULP: It probably isn’t that succinct or prophetic. But I would say the problems are only going to get harder. And the way to solve them is to communicate and collaborate. That’s the only way we will be successful.

Terry Fulp

Education: Bachelor’s degree, University of Tulsa; master’s degrees, University of Colorado and Stanford University; doctorate, Colorado School of Mines

Previous jobs: Deputy Regional Director, Lower Colorado Region; Area Manager, Boulder Canyon Operations Office; Manager, River Operations, Boulder Canyon Operations Office; Principal Investigator, Department of the Interior Watershed and River Systems Management Research Program; Manager, Geophysical Operations, Senior Geophysicist, Arco Oil and Gas Company (formerly Atlantic Richfield Company)

Fun fact: “When I first went to college and graduate school, I had no idea at all that I would end up in water. Through a bit of serendipity, I’d say, I just fell in love with it and have loved it for the 31 years or so.”

This story originally appeared on Western Water on November 6, 2020.

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @GaryPitzer

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.