By Yadu Pokhrel, Michigan State University

The world watched with a sense of dread in 2018 as Cape Town, South Africa, counted down the days until the city would run out of water. The region’s surface reservoirs were going dry amid its worst drought on record, and the public countdown was a plea for help.

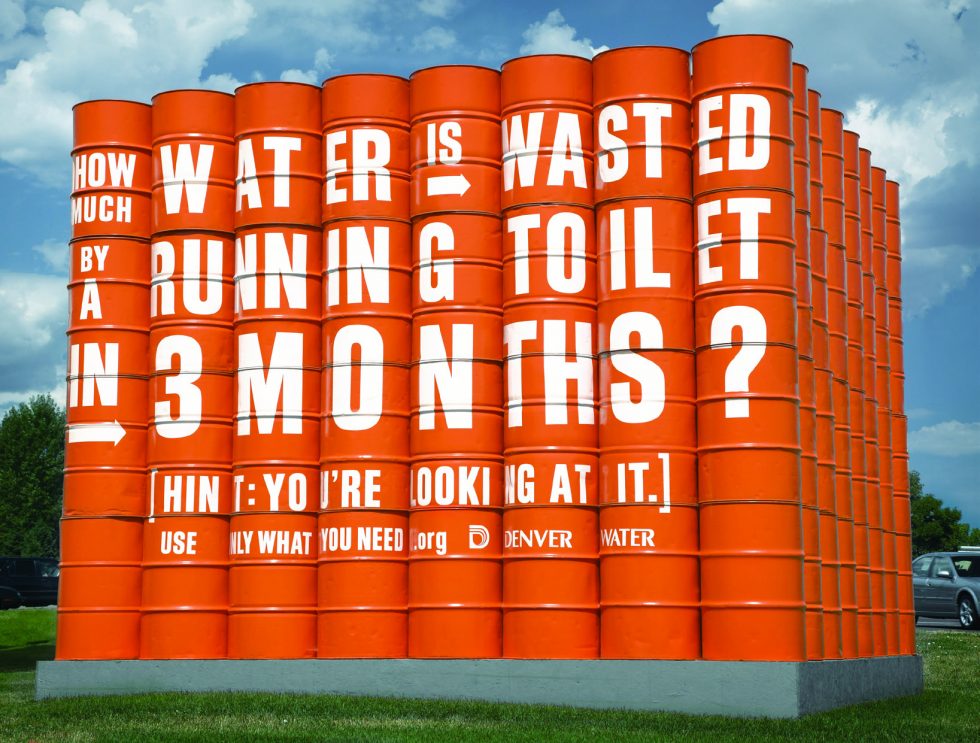

By drastically cutting their water use, Cape Town residents and farmers were able to push back “Day Zero” until the rain came, but the close call showed just how precarious water security can be. California also faced severe water restrictions during its recent multiyear drought. And Mexico City is now facing water restrictions after a year with little rain.

There are growing concerns that many regions of the world will face water crises like these in the coming decades as rising temperatures exacerbate drought conditions.

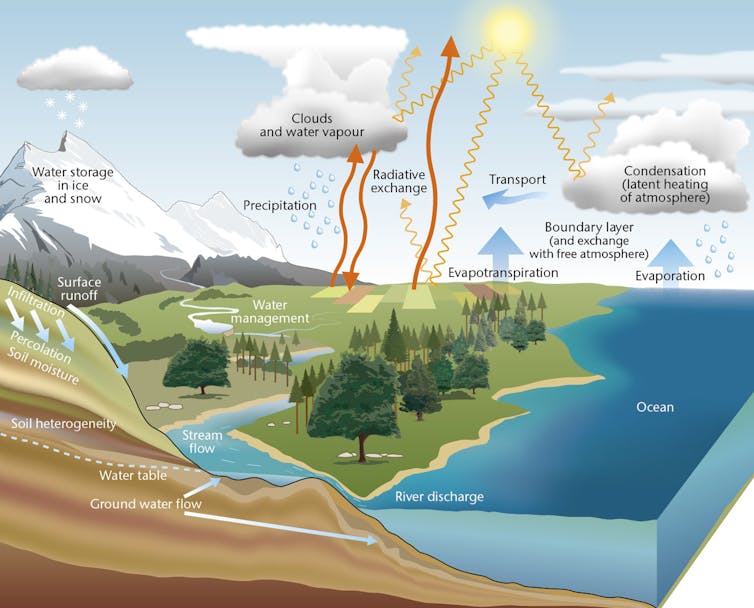

Understanding the risks ahead requires looking at the entire landscape of terrestrial water storage – not just the rivers, but also the water stored in soils, groundwater, snowpack, forest canopies, wetlands, lakes and reservoirs.

We study changes in the terrestrial water cycle as engineers and hydrologists. In a new study published Jan. 11, we and a team of colleagues from universities and institutes around the world showed for the first time how climate change will likely affect water availability on land from all water storage sources over the course of this century.

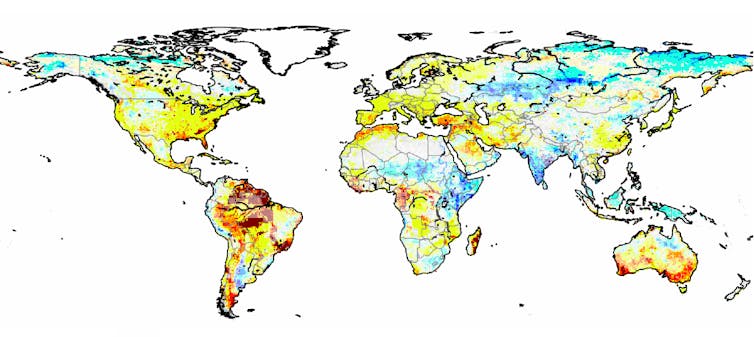

We found that the sum of this terrestrial water storage is on pace to decline across two-thirds of the land on the planet. The worst impacts will be in areas of the Southern Hemisphere where water scarcity is already threatening food security and leading to human migration and conflict. Globally, one in 12 people could face extreme drought related to water storage every year by the end of this century, compared to an average of about one in 33 at the end of the 20th century.

These findings have implications for water availability, not only for human needs, but also for trees, plants and the sustainability of agriculture.

Where the risks are highest

The water that keeps land healthy, crops growing and human needs met comes from a variety of sources. Mountain snow and rainfall feed streams that affect community water supplies. Soil water content directly affects plant growth. Groundwater resources are crucial for both drinking water supplies and crop productivity in irrigated regions.

While studies often focus just on river flow as an indicator of water availability and drought, our study instead provides a holistic picture of the changes in total water available on land. That allows us to capture nuances, such as the ability of forests to draw water from deep groundwater sources during years when the upper soil levels are drier.

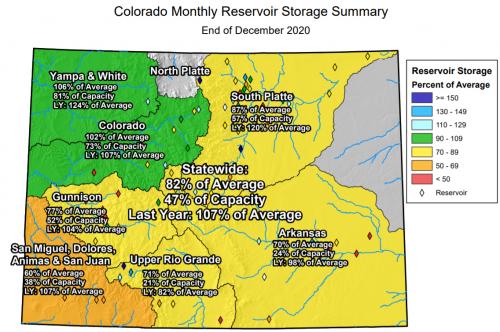

The declines we found in land water storage are especially alarming in the Amazon River basin, Australia, southern Africa, the Mediterranean region and parts of the United States. In these regions, precipitation is expected to decline sharply with climate change, and rising temperatures will increase evaporation. At the same time, some other regions will become wetter, a process already seen today.

Our findings for the Amazon basin add to the longstanding debate over the fate of the rainforest in a warmer world. Many studies using climate model projections have warned of widespread forest die-off in the future as less rainfall and warmer temperatures lead to higher heat and moisture stress combined with forest fires.

In an earlier study, we found that the deep-rooted rainforests may be more resilient to short-term drought than they appear because they can tap water stored in soils deeper in the ground that aren’t considered in typical climate model projections. However, our new findings, using multiple models, indicate that the declines in total water storage, including deep groundwater stores, may lead to more water shortages during dry seasons when trees need stored water the most and exacerbate future droughts. All weaken the resilience of the rainforests.

A new way of looking at drought

Our study also provides a new perspective on future droughts.

There are different kinds of droughts. Meteorological droughts are caused by lack of precipitation. Agricultural droughts are caused by lack of water in soils. Hydrological droughts involve lack of water in rivers and groundwater. We provided a new perspective on droughts by looking at the total water storage.

We found that moderate to severe droughts involving water storage would increase until the middle of the 21st century and then remain stable under future scenarios in which countries cut their emissions, but extreme to exceptional water storage droughts could continue to increase until the end of the century.

That would further threaten water availability in regions where water storage is projected to decline.

Changes driven by global warming

These declines in water storage and increases in future droughts are primarily driven by climate change, not land-water management activities such as irrigation and groundwater pumping. This became clear when we examined simulations of what the future would look like if climate conditions were unchanged from preindustrial times. Without the increase in greenhouse gas emissions, terrestrial water storage would remain generally stable in most regions.

If future increases in groundwater use for irrigation and other needs are also considered, the projected reduction in water storage and increase in drought could be even more severe.

Yadu Pokhrel is Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.