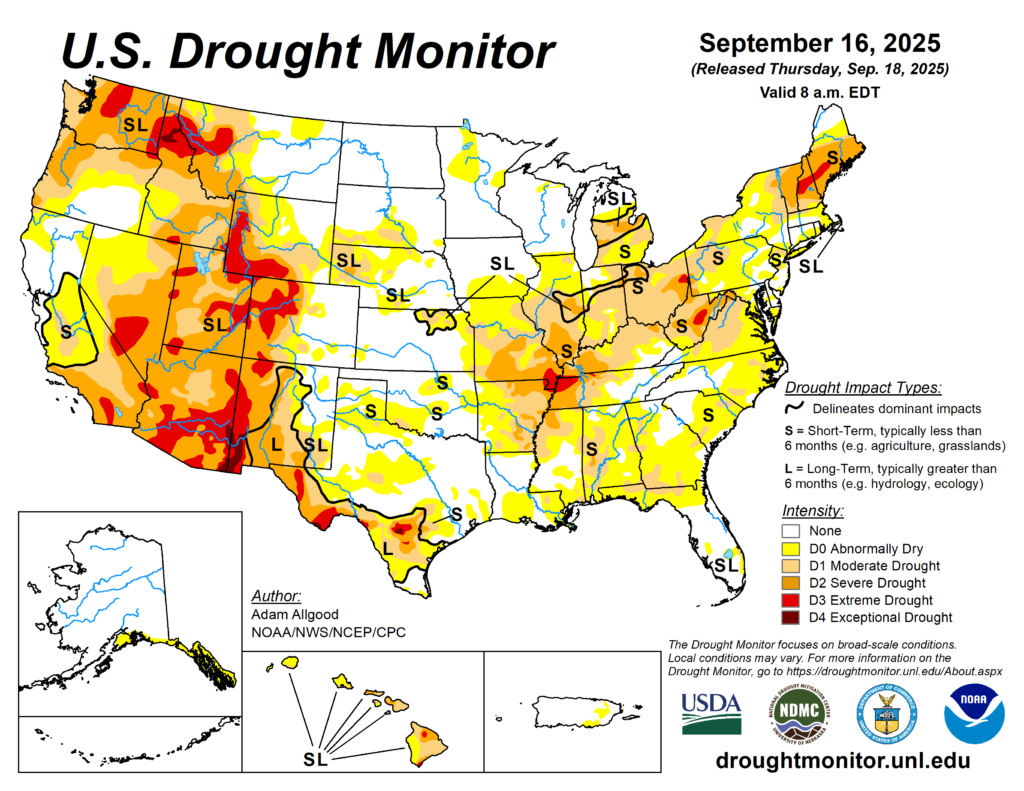

The American Southwest has been gripped by an epic drought that has lasted decades and strained the fast-growing region’s naturally limited water resources.

The megadrought—thought to be the worst in at least 1,200 years—has caused reservoir levels to plummet on the Colorado River and shriveled the Rio Grande. The dry times have also stressed imperiled ecosystems, heightened wildfire risks and curtailed outdoor recreation.

While the drought’s consequences are easy to see, its causes and prognosis are trickier to disentangle, requiring scientists to look deeply into precipitation deficits, rising temperatures and changing patterns in the atmosphere and ocean.

Long before humans began altering the climate with greenhouse gases and other air pollutants, the Southwest was subject to feast-or-famine weather featuring extreme dry spells, raising the possibility that this current drought is just part of that natural variability.

What scientists are exploring now is how the human touch is imprinted on the drought due to our ongoing transformation of the climate, atmosphere and oceans.

Three recent scientific studies identify human emissions as a key driver in the precipitation declines that have helped cause the Southwest’s current drought, which has been made much worse by rising temperatures due to climate change.

The papers, published in the July 9 issue of Nature Geoscience and the August 13 issue of Nature, focus on what’s been happening in and above the Pacific Ocean to help explain recent precipitation deficits in the Southwest. As carbon emissions continue to rise, all three papers conclude that human-caused warming is likely to make drought a more persistent feature in the decades ahead.

The three recent studies examine why changes in and above the ocean have shifted storm tracks and made the Southwest’s weather drier, but that’s not the whole story about the drought. The picture is even bleaker when we account for what’s happening to the region’s warming landscape and an increasingly thirsty atmosphere.

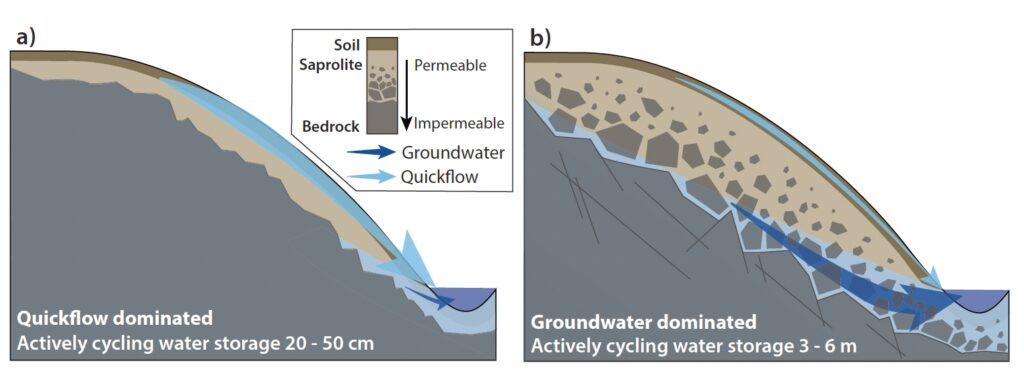

Another line of research has found that higher temperatures alone are causing the Southwest to “aridify” by drying out soils, boosting evaporation rates and shrinking the snowpack. Known as a “hot drought,” this aridification due to warming would be troubling enough for the Southwest’s water resources and society. But the three recent studies, which focus on precipitation shortfalls, add another level of worry: relief falling from the skies as raindrops and snowflakes appears increasingly unlikely.

Study 1: Why the Pacific’s rhythm is stuck

One of the studies, “Human emissions drive recent trends in North Pacific climate variations,” focuses on the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and why it has been stuck, rather than oscillating over recent decades as its name would suggest.

The PDO is a natural rhythm in sea-surface temperatures in the North Pacific Ocean that has warm and cool phases. The cycle, which is similar to the El Niño/La Niña pattern in the tropical Pacific, was thought to last about 20 to 30 years, but in recent decades it has predominantly been in the cool or “negative” phase, which tends to make the Southwest drier.

“The PDO has been locked in a consistent downward trend for more than three decades, remanding nearby regions to a steady set of climate impacts,” according to the study. “The ongoing, stubbornly persistent, cold phase of the PDO is associated with striking long-term trends in climate, including the rate of global warming and drought in the western United States.”

The conventional scientific understanding of the PDO holds that the pattern waxes and wanes largely due to natural “internal” variability. But this recent study, which relies on 572 climate simulations processed on supercomputers, argues that the PDO is, in fact, very much influenced by human activities and our air pollution. These external forces account for 53% of the variation in the PDO.

“Overall, we find that human activity is a key contributor to multi-decadal trends in the PDO since the 1950s,” according to the paper.

It wasn’t always this way. Between 1870 and 1950, the PDO’s changes were internally generated, with external forces explaining less than 1% of the variability.

“It seems like as long as emissions continue, we’re going to be stuck in this current phase of drought,” said lead author Jeremy Klavans, a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder. “If emissions were to abate, we think that the PDO would be able to vary freely again, and drought would be, again, a thing of chance. There would be the chance to end the drought.”

The researchers say they used an “extraordinarily large ensemble” of climate simulations to isolate the signal of human-caused climate change from the noise of natural variability.

“It takes a really large ensemble to find this signal, and that’s because we think that the signal-to-noise ratio in climate models is too low,” Klavans said.

That’s distressing news for the region’s water managers, who are already grappling with limited supplies. “We expect there to be reduced water supply in the form of precipitation, including snowfall, in the next 20, 30 years, so as they’re making planning decisions for how to allocate water resources or what infrastructure to build, they should expect less precipitation,” Klavans said.

“It certainly seems that in the near term, given the choices that we’ve made, the PDO will continue to be stuck in drought,” Klavans said.

Study 2: Deep drought long ago offers insights for today

This isn’t the first time the Southwest has faced a megadrought.

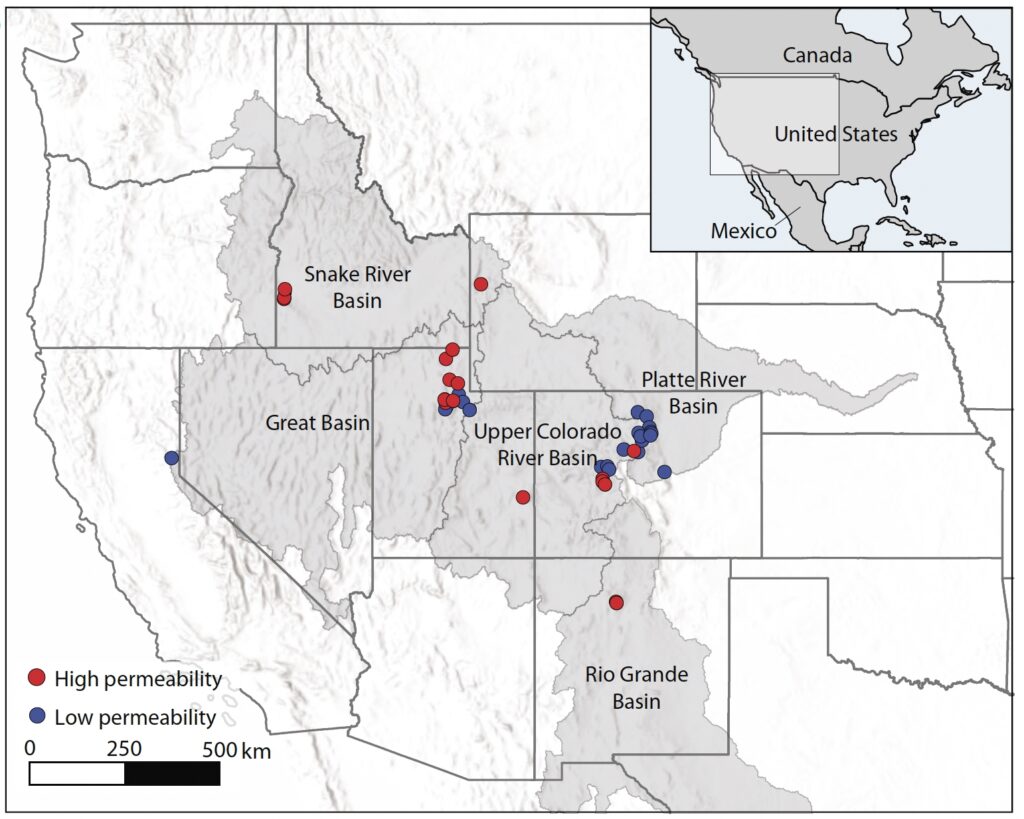

Another study, “North Pacific ocean–atmosphere responses to Holocene and future warming drive Southwest US drought,” looks back about 6,000 years ago to a time known as the mid-Holocene. Back then, the Southwest suffered a monster drought lasting thousands of years, but this occurred many millennia before humans began changing the climate with our emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants.

During the mid-Holocene, there was a different external force at play: an increase in the amount of solar radiation hitting the Northern Hemisphere during the summer, which also altered vegetation patterns on the land.

In a process known as the Milankovitch Cycles, the Earth’s orbit and movement change regularly over the span of tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of years. Like a spinning top, the planet wobbles. The tilt of its axis also oscillates back and forth. And Earth’s orbit around the sun alters from a near-perfect circle to a slightly more elliptical path.

The Milankovitch Cycles caused more sunlight to hit the Northern Hemisphere in summer during the mid-Holocene warming. One of the effects was a more vigorous West African monsoon and the greening up of the Sahel and Sahara deserts, which caused those areas to absorb more heat as the land surface darkened. Similar processes happened elsewhere. The paper concludes that this external forcing had a major impact on the Pacific Ocean and the PDO, similar to how human-caused warming is playing out today and into the future.

“People used to think that droughts in the Southwest were just occurring kind of like as a random roll of the dice, and now we can see that actually it’s like a pair of loaded dice,” said lead author Victoria Todd, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas studying paleoclimatology. “This drought is occurring in wintertime, which is really important for snowpack in the Rockies and its role in Colorado River flow and Western U.S. water resources in general.”

The authors write that “our results suggest that these precipitation deficits will be maintained by a shift to a more permanent negative PDO-like state as long as hemispheric warming persists.”

“Such sustained drying and intense reductions in winter precipitation would have catastrophic impacts across the Southwest United States, particularly in the Colorado River Basin,” according to the paper.

Todd and co-authors investigated what happened during the mid-Holocene by using an analysis of leaf waxes extracted from the cores of lake sediments in the Rocky Mountains. Plants create waxy coatings on their leaves to minimize water loss and protect themselves. These hardy waxes can persist for ages when they’re deposited into sediments, allowing them to reveal critical clues about what the Earth was like when the plant was alive. By analyzing the leaf wax’s isotopes—special forms of chemical elements—researchers can paint a picture of precipitation patterns long ago.

The findings about the mid-Holocene and their analysis of modern climate projections led the researchers to conclude that current models underestimate the size of the precipitation deficits caused by warming. Both in the past and the present, the warming impacts the PDO and steers storms away from the Southwest.

If the Southwest’s drought were just due to natural variability—a fair roll of the dice—we’d expect the PDO to get unstuck eventually and for the dry spell to break. But the research concludes that pure chance is no longer governing the system. Humans are tilting the odds.

“If global temperatures keep rising, our models suggest the Southwest could remain in a drought-dominated regime through at least 2100,” co-author Timothy Shanahan, associate professor at the University of Texas’ Jackson School of Geosciences, said in a press release.

“Many people still expect the Colorado River to bounce back,” Shanahan said. “But our findings suggest it may not. Water managers need to start planning for the possibility that this drought isn’t just a rough patch—it could be the new reality.”

Study 3: The effects of aerosols and tropical ocean warming

The third paper, “Recent southwestern US drought exacerbated by anthropogenic aerosols and tropical ocean warming,” offers a hint of optimism but also warns about long-term drought in the Southwest.

The study identifies two human-caused drivers for the shortfall in winter-spring precipitation in the region: the effects of aerosol pollution in the atmosphere and global warming’s impact on ocean temperatures in the tropical Pacific. These forces have weakened the Aleutian Low, the semi-permanent low-pressure system in the North Pacific that directs storms toward the Southwest when it’s stronger.

The study concluded that the post-1980 period in the Southwest has seen record-fast drying of soil moisture due to the precipitation declines and human-caused warming. Natural variability still plays a significant role in the Southwest’s precipitation, according to the researchers, but humanity is making its mark.

“We are not saying 100% it’s because of climate change or because of human emissions, but there’s a role from human emissions,” said lead author Yan-Ning Kuo, a Ph.D. candidate in atmospheric science at Cornell.

Aerosols may conjure deodorant sprays, but in this context, they refer to a broad class of airborne particles that are emitted by human activities, such as burning fossil fuels, and natural causes, such as dust from deserts or sea salt from the ocean.

Some aerosols, such as the sulfates emitted when coal and oil are burned, reflect incoming sunlight and can have a cooling effect. Others, such as sooty black carbon, absorb solar radiation and have a warming effect. Aerosols can also affect cloud formation.

In this study, the authors argue that aerosols can have a significant effect on the atmosphere as they drift eastward from Asia, where booming economies and lax regulations in some areas have caused air pollution to soar in recent decades.

“We actually feel like there’s a hope for good news on the precipitation side because as we clean up aerosols, precipitation might rebound a little bit,” said co-author Flavio Lehner, assistant professor in Cornell’s Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Department.

But while reduced aerosol pollution might help the Southwest’s drought, the emissions of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, keep rising, and warming temperatures continue to aridify the Southwest’s landscape.

“From a precipitation perspective, we might see a recovery in the next decade or two, but together with the continued warming, that might not help much with the drought,” Lehner said. “In none of these scenarios, I think everybody would agree, does it look like the Southwest is not going to be in trouble.”