By Heather Sackett

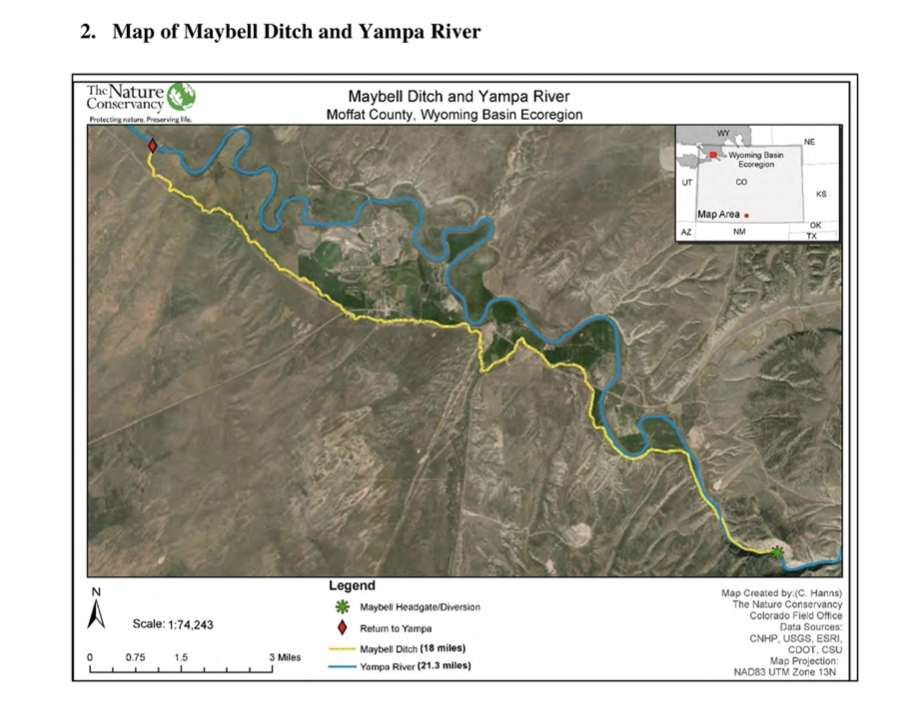

The Maybell Ditch is the largest diversion on the Yampa River and irrigates about 2,500 acres of grass and alfalfa in northwest Colorado. But the remote and antiquated headgate, along with a hazardous diversion structure and 18 miles of nearly flat canal, create problems for irrigators, boaters and endangered fish alike.

Now the Maybell Irrigation District and The Nature Conservancy are working together on an ambitious project to rehabilitate and modernize the historic structure with the goal of improving conditions for all the water users on this stretch of river. So far, TNC has secured about $3.5 million in funds for the project, which it hopes can begin next summer.

The Yampa River flows from the Flat Tops Wilderness, through the city of Steamboat Springs, then turns west and eventually joins with the Green River in Dinosaur National Monument. Along the way it turns the semi-arid landscape of Routt and Moffat counties into a ribbon of green, irrigated meadows.

In recent years the Yampa has started experiencing issues that have long been a part of other river basins like over-appropriation, calls and water shortages.

“That reach has seen declines in water levels over time with drought and long-term climate impacts,” said Jennifer Wellman, TNC project manager. “(The Maybell Ditch project) was one of those that rose to the surface where we could hopefully work with the water users to have a greater impact in that basin … . That whole reach is really special, and it warrants more water if it’s available, especially during the low flow periods.”

Challenges for irrigators, boaters, fish

Maybell Irrigation District manager Mike Camblin said historically some ranchers couldn’t get their full amount of water unless the ditch, which was constructed in the 1890s, was running full blast.

“We had one field where if the ditch wasn’t full, they couldn’t get it wet because there wasn’t enough elevation to it,” he said. “It was too flat.”

That meant more water was being sent through the ditch as “push water” to make sure flows make it to dry fields. It also meant more water was flowing back into the Yampa River at the end of the approximately 18-mile-long ditch, known as tailwater. If there’s too much tailwater, that can mean a ditch is taking more out of the river than it is able to use, a no-no according to the state Division of Water Resources.

A first round of improvements to the ditch added a liner to reduce seepage and check structures, which slow the flow of water. Those measures only partially addressed the issues.

The project that is now being proposed is much more extensive and involves reconstructing the diversion and modernizing the headgate, which controls the flow of water from the river into the ditch. By fixing a grade control structure — essentially arranging boulders in mid-stream that push up the water in the river upstream of the headgate — it creates more elevation to allow gravity to move water into the ditch, which should reduce the need to push water. It will also smooth out a passage for both fish and boats.

Remote location

The twin, circular, century-old headgates are rusted and hard to operate.

“There’s no way those things are easy to adjust,” said Erin Light, Division 6 engineer at the state Division of Water Resources. “Quite frankly, if the water commissioner had to adjust it, I don’t think he or she could. We would have to rely on (the irrigation district) to do that, which is not preferred.”

The remote location of the headgate — a three-mile round trip hike down the rugged Juniper Canyon off an already-remote dirt road — is a challenge for the district. When all the headgates on the ditch are opening and closing according to the differing schedules and water needs of the irrigators, it can be hard to coordinate the manual operation of the main headgate. The new headgate will be automated and controlled remotely.

“That’s a four- or five-hour deal by the time you drive up there, walk up there, adjust it and drive home,” Camblin said. “The automation on that will be huge. As far as management, it will be our biggest tool.”

But construction won’t be easy. Heavy equipment can’t make it down to the river along the ditch and will have to access the diversion using newly constructed roads on Bureau of Land Management land. The BLM considers the ditch a cultural resource and project proponents will have to be careful to avoid impacts to it.

Western Colorado Area Manager for JUB Engineers Luke Gingerich explained the complexities of the project on a site visit in July.

“They are going to have to create a couple miles of nice road to get in,” Gingerich said. “It will be a large disturbance and we’ve got to come back and make sure we return this as close as we can to the condition it was in before.”

According to Camblin, it was the federal Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program that first pushed the district to take a look at where it could manage its water better. That stretch of river is designated critical habitat for species of endangered fish. Water is released out of the upstream Elkhead Reservoir for the fish, and the new automated headgate will allow the Maybell Ditch to more easily let that water flow past it, to get to where it’s needed.

Boon for boaters

The diversion reconstruction project will also be a boon for boaters. River advocacy nonprofit Friends of the Yampa said in a letter of support for the project that the Maybell Diversion is the most significant barrier for safe, passable recreation along a 200-mile stretch of the Yampa River. Boaters often have to get out to portage the rapid formed by the diversion structure. The new diversion will create a boat passage, connecting two sections of boatable river.

At July’s site visit, recreation and education coordinator for Friends of the Yampa Kent Vertrees said he’s grateful for the collaboration between the agriculture, recreation and environmental water users.

“As a recreation person, I’ve said all along we get the dregs of all the other water users,” Vertrees said. “We rely on agriculture more than anyone to make sure there’s water in the river. It’s really great, our partnerships in northwest Colorado.”

But that partnership was a bit of a hard sell at first, Camblin said. Some Maybell Ditch irrigators were skeptical about a project spearheaded by an environmental group. Tensions can sometimes run high between irrigators, who take water out of rivers, and environmental groups, who want to leave water in rivers. Camblin said the district held several meetings between irrigators and TNC to assure water users their water rights or how they manage their ranch wouldn’t be threatened.

“One of our goals we talked about when we started this was, we wanted to show people the agriculture community can work with groups they don’t normally work with,” Camblin said. “We are hoping other ag communities say, ‘Hey, you know what? Some of this stuff is possible. I might have to reach across the table to make it work but this will be a beneficial project to so many people.’”

The headgate and diversion reconstruction could come with a hefty price tag and TNC is still fundraising for what could end up costing more than originally thought due to supply chain interruptions and inflation. The project has secured almost $3.5 million so far, nearly $2 million of which comes from a Bureau of Reclamation WaterSMART grant. The Colorado Water Conservation Board has contributed about $1 million so far; the Colorado River Water Conservation District will give $500,000; $40,000 will come from the Yampa River Fund and the irrigation district is also contributing money and in-kind resources. However, the total final price tag remains unknown and is likely to be higher than what’s already been secured. Wellman said some of the additional funding needed will also come from the National Resources Conservation Service.

Aspen Journalism covers water and rivers in collaboration with The Aspen Times. This story appeared in the Sept. 11 edition of The Aspen Times, the Sept. 13 edition of the Craig Press.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.