By Olivia Emmer

As two major new water storage projects designed to capture the flows of the drought-strapped Colorado River are rising on Colorado’s urban Front Range, observers say they represent the end of an era on the river.

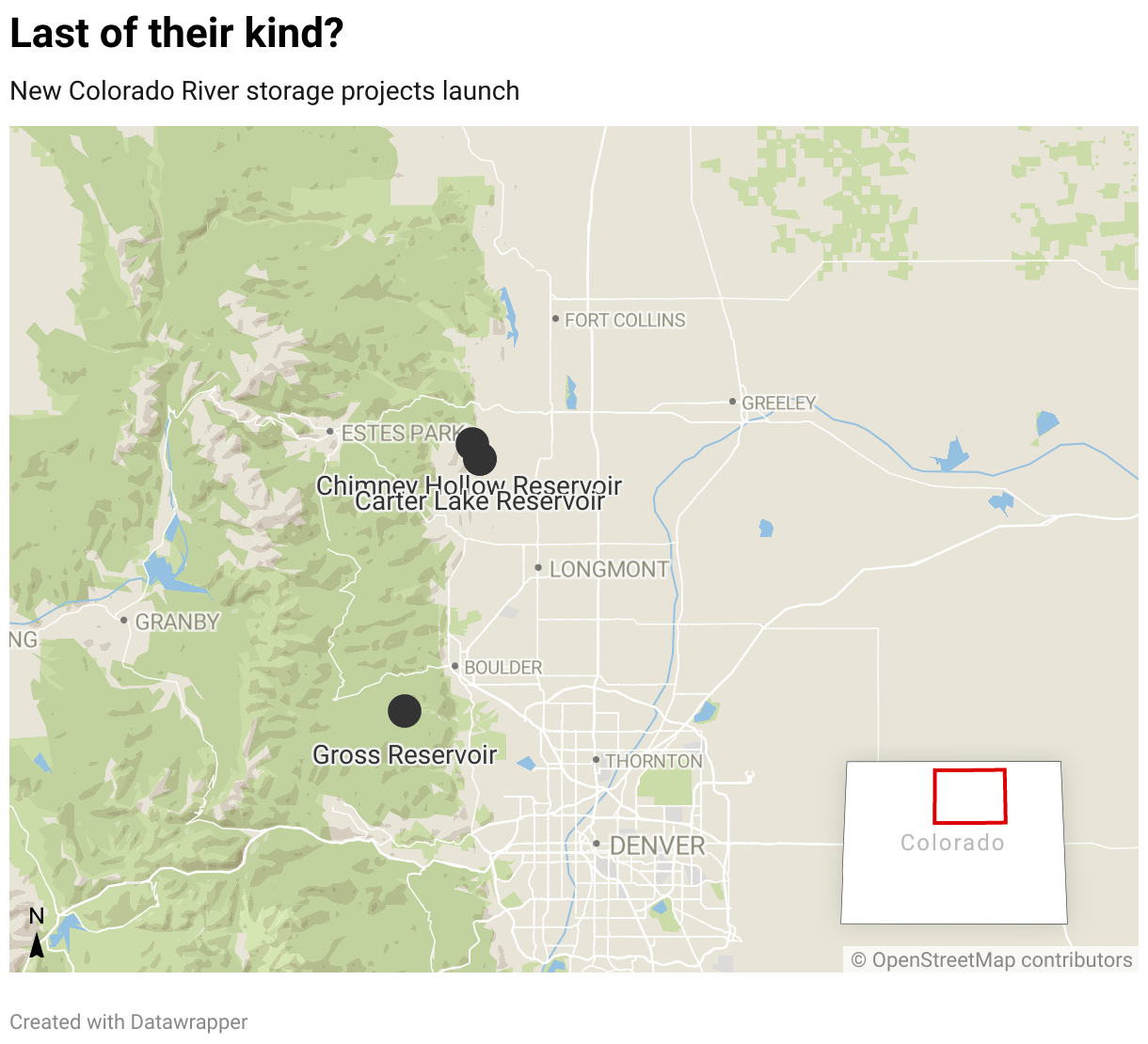

The projects, Northern Water’s Chimney Hollow Reservoir west of Berthoud, and Denver Water’s Gross Reservoir Expansion, in Western Boulder County, both more than 20 years in the making, will store an additional 167,000 acre-feet of water, the majority from the Colorado River. That’s enough water for more than 320,000 new homes.

The projects come during a period of crisis on the river, with the federal government in June ordering Western states to find radical new ways of cutting water use by next month to stabilize the deteriorating river system.

“These two projects, [Chimney Hollow] and the Gross Reservoir Expansion, might be the last of their kind. They are coming in under the wire of a change in how we have to see the Colorado River – it’s not something we can keep tapping,” said Jeff Lukas, an independent water and climate researcher and consultant, who spent a decade working for the Western Water Assessment at the University of Colorado.

The river basin includes seven states and Mexico. In the U.S., Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming comprise the Upper Basin, while Arizona, California and Nevada comprise the Lower Basin.

One hundred years ago, the Colorado River Compact of 1922 divided 15 million acre-feet of water equally between the Upper and Lower Basin states, but in this drier world, the river likely provides an average closer to 13 million acre-feet. Climate change is expected to further reduce that flow. More water has been allocated to the two basins than is available most years.

Northern Water and Denver Water are building new water storage to meet the demands of a growing urban Front Range and to provide themselves more flexibility in managing their Colorado River supplies.

Northern Water delivers municipal and agricultural water to about a million people over about 1.6 million acres. They bring over about 220,000 acre-feet of water each year from the West Slope to the Front Range via the Colorado Big Thompson Project and Windy Gap. About half is used for agriculture and half for cities and industry.

Joe Donnelly, Northern’s project manager for the Chimney Hollow Reservoir Project, said the project is a major mechanical and logistical feat, with water passing through two pump stations, five hydropower plants, seven reservoirs, and nearly 20 miles of tunnels before reaching Chimney Hollow.

Chimney Hollow will be an off-channel reservoir with 90,000 acre-feet of capacity and will sit just west of Carter Lake in Larimer County. According to the project’s website, it will be the second-ever asphalt-core dam in the United States and, once dam construction is fully underway, the on-site rock quarry “will be producing 63,000 tons of material per day, making it one of the largest mining operations in Colorado.” The project broke ground in August 2021.

Northern Water plans to begin storing water in Chimney Hollow Reservoir upon completion in 2025 and hopes to fill it within three years by storing approximately 30,000 acre-feet of water each year out of the Windy Gap Project’s average of 48,000 acre-feet of water per year.

In Boulder County, less than 50 miles south of Chimney Hollow, sits Denver Water’s Gross Reservoir. Originally built in the 1950s, it was designed with expansion in mind. Construction recently began to increase the height of the dam from 340 feet to 471 feet. This will add 77,000 acre-feet of storage, more than doubling its current capacity. Water from the Colorado River Basin is diverted under the Continental Divide through the Moffat Tunnel into South Boulder Creek, then stored in Gross Reservoir, and then delivered via South Boulder Creek to other Denver Water infrastructure.

Denver Water serves about 1.5 million people, a number that is slated to grow by 1 million residents by 2040, according to its website. All of their water goes to municipal and industrial uses. In 2021 Denver Water diverted about 140,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water, approximately half their supply.

“As the climate warms and the atmosphere becomes wetter because of more evaporation, that causes more significant storm activity. If you look right at the Continental Divide where our facilities are, the climate models are basically split as to whether we’re going to see more or less precipitation,” says Denver Water CEO Jim Lochhead. The expansion of Gross Dam will capitalize on “those significant events that we believe will occur in the future with climate change.”

Denver Water has also cited resiliency goals as part of its motivation for expanding Gross Reservoir’s capacity. “The Buffalo Creek and Hayman Fires caused significant sediment loads [in our water supply] and exposed a vulnerability in our system. Eighty percent of our water supply is in the south end of our system,” explains Lochhead. “The other event was the severe drought in 2002. During that drought, the north end of our system almost ran out of water.”

Northern Water and Denver Water both say that these added storage projects will help them protect their customers from climate variability. They are betting on enough wet years to fill their reservoirs to help get through the more frequent dry years, even as the population in their service areas grows.

“If we’re thinking about putting in new water storage projects, all the risk is really on the dry side. Are we going to be able to fill this and get the yield we’re assuming in our economic analysis for the project?” cautions Lukas. “I would be much more focused on all of the dry scenarios, the lower runoff outcomes coming out of the climate model informed projections, than the relatively fewer projections that suggest we could get more runoff in the future.”

In the face of shrinking river flows, some environmentalists and other experts are critical of building more water storage when existing reservoirs struggle to stay full and river ecosystems are more stressed than ever.

Save the Colorado sued both storage projects as part of its mission to oppose dams and diversions on the Colorado River. Director Gary Wockner takes a hard stance, saying “These two projects will further drain and destroy the Colorado River at the exact moment the system is collapsing.”

But other environmental organizations take a more pragmatic position. Legal Counsel for the Colorado Water Project at Trout Unlimited, Mely Whiting, said that her organization didn’t oppose these two storage projects because they were a preferred alternative to building the Two Forks Dam, a vetoed project that would have inundated some of the headwaters of the South Platte under 1 million acre-feet of water.

Whether a warming climate will create more precipitation and improve storage levels is a major question.

While Chimney Hollow and the Gross Reservoir Expansion are underway, any future storage in Colorado or elsewhere will be problematic, Lukas says.

“Climate change cuts both ways with respect to storage. It both makes it more appealing, and it is a potential tool for resilience, but only if that reservoir can be filled enough to create the benefits that are expected,” explains Lukas, “If those storage projects involve transbasin diversions from the Colorado [River], that is looking increasingly untenable in a multi-state and a national-political sense, let alone at the local, East Slope-versus-West Slope context. To propose new diversions out of the Colorado River Basin to anywhere, for anything, is really going to be looked at sideways unless things really improve in the basin.”

Olivia Emmer is a freelance journalist based in Carbondale, Colorado. She can be reached at olivia@soprissun.com.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.