By Jerd Smith

Drought-strapped Lake Powell won a major reprieve last week with two emergency agreements that will provide 1 million acre-feet (maf) of Colorado River water this year to boost lake levels and protect its hydropower production.

The water will come from an emergency release of 500,000 acre-feet from Utah’s Flaming Gorge Reservoir, and a 500,000 acre-foot reduction in releases from Powell’s Glen Canyon Dam.

That’s as much water as it would take to fill Colorado’s Lake Dillon four times, and it will add a significant buffer to Powell, which has dropped to just over 5 maf of stored supplies. The lake has the capacity to store 26 maf.

“This is a short-term Band-Aid,” said Amy Ostdiek, who helped oversee the drought negotiations for the Colorado Water Conservation Board, the state’s lead agency for water planning. “We are going to have to consider the long-term solutions and they have to be balanced.”

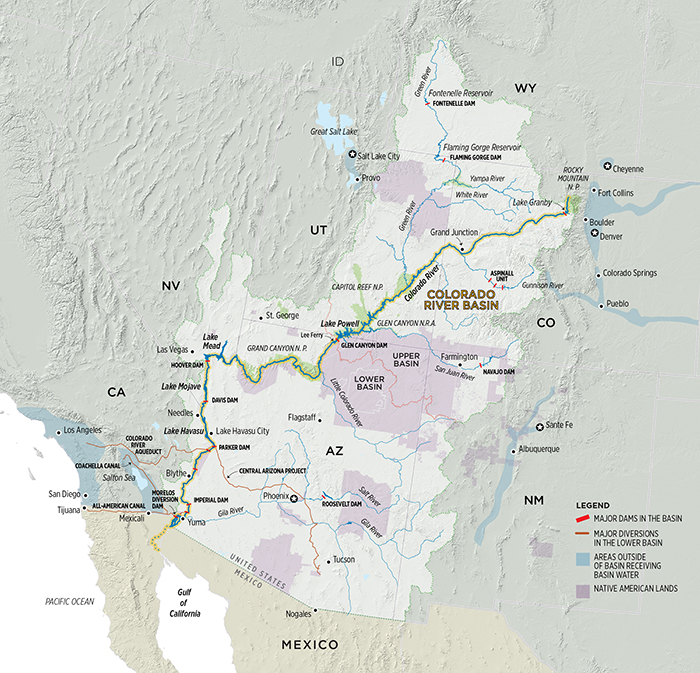

The Colorado River Basin covers seven states, as well as Mexico. The basin is divided into an Upper Basin — Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico — and Lower Basin — Arizona, California and Nevada.

Under the 1922 Colorado River Compact, Colorado and the other Upper Basin states must deliver 7.5 maf of water to the Lower Basin at Lee Ferry, Ariz., just downstream of Glen Canyon Dam, on a 10-year running average. This year the Upper Basin will deliver just 7 maf from Lake Powell.

But because the 10-year running average stands at roughly 9 maf, there is still time to help the system come back into balance before the Lower Basin states could legally call for more water than they currently receive.

Lake Powell is the Upper Basin’s largest storage pool on the system and is designed to ensure the four Upper Basin states can meet their legal water delivery obligations to the Lower Basin states. Because of those obligations, Colorado water users are closely monitoring the ongoing declines in Powell, with the threat to hydropower production seen as a dangerous precursor to a water shortage that could trigger a legal compact crisis.

Last year, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation ordered the release of 125,000 acre-feet of water from Flaming Gorge, and another 36,000 acre-foot release from Colorado’s Blue Mesa Reservoir.

This year is expected to be slightly better from a snowpack and water supply perspective. In Colorado, for instance, snowpack ahead of the spring runoff, sits at 91% of average, above last year’s 79% mark.

But that’s not enough moisture to help any of the reservoirs on the Colorado River’s seven-state system recover, water officials said. It should be enough, however, to protect hydropower production, which has been steadily dropping as Lake Powell has declined.

But it’s not just hydropower and water supplies that are causing concern. The drop in reservoir levels is affecting thousands of boaters and campers across the West, who flock to these storage pools every summer to camp, fish and boat.

John Rauch and his family have operated Cedar Springs Marina on Flaming Gorge for decades. Last year, as he watched the lake shrink, he acted quickly, moving boat docks and accommodating customers whose recreation plans were being altered on a daily basis.

This year’s announcement was no surprise, Rauch said, but the jump in the amount of water being released, a nearly four-fold increase, is worrisome.

Equally concerning is the prospect that more releases will be required next year, Rauch said.

“I think we’re going to lose a lot more water,” he said.

Lake Powell, which can store roughly 26 maf of water when full, and its sister reservoir, Lake Mead, with 29.4 maf of storage, are two of the largest reservoirs in the United States. But upstream are three more: Utah’s Flaming Gorge, which holds 1.8 maf when full, Colorado’s Blue Mesa which holds 900,000 acre-feet, and New Mexico’s Navajo Reservoir, with 1.7 maf of storage.

A 20-year megadrought, considered to be the worst in 1,200 years, including two back-to-back intense drought periods during 2020 and 2021, has left each of the reservoirs well below their former levels, with Blue Mesa, for instance, sitting at roughly 40% of capacity with no prospect of refilling this year, and Lake Powell down to about 25% of capacity.

After weeks of closed-door talks with officials from the seven states, Reclamation, which operates the reservoirs, opted to tap Flaming Gorge again this summer because it sits high in the system and could accommodate a release easier than Blue Mesa or Navajo, officials said.

That move, along with the 500,000 acre-foot cutback in releases from Lake Powell, should be enough to protect hydropower production this year, said Becky Mitchell, director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

How that water will be restored to the states is unclear. Under the terms of a historic set of Drought Contingency Plans approved in 2019, so-called “recovery” of these water supplies is to be considered when the federal government decides the system is healthy enough again, according to Reclamation.

Reclamation declined an interview request on the new agreements, but in documents released last week it said that little if any recovery is likely over the next four years.

Drought has plagued the Colorado River since the early 2000s and in 2007 the seven states agreed to a hard-fought plan to begin jointly managing the system, hoping that the drought would end before the agreement, known as the Colorado River 2007 Interim Guidelines, expires in 2026.

All seven states are gearing up to renegotiate those guidelines, a process expected to take several years. And water officials across the region are calling for a recognition that the river can no longer produce the water quantities envisioned even as recently as the early 2000s.

What that may mean for water users isn’t clear yet, but all seven states have begun cutting back their use of Colorado River supplies, either because the river has run physically short of water, as in the Upper Basin states, or in the Lower Basin, due to the 2007 guidelines, which tie water-use reductions to levels in lakes Powell and Mead.

For John Rauch, adapting to a more water-short world is going to be a huge undertaking, though not an impossible one.

“It’s a complicated problem,” he said. “We’re going to do everything we can … but it’s going to take a lot of snow.”

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.