Inventories of irrigation ditches across the Western Slope have become common in recent years and water managers say they have merit.

But there is no requirement that the individual studies — which look at things such as efficiency and opportunities for repairs and upgrades — be made public, even though they are often paid for with public money. This doesn’t sit well with some who say the public has a right to know exactly how taxpayer dollars are being spent and how one of the West’s most precious and dwindling resources is being used.

“(Agriculture) is where 80% to 90% of the water gets used, and if we were more efficient, we could leave more water in the river — that’s the bottom line,” said Ken Ransford, recreation representative to the Colorado Basin Roundtable and who also acts as Aspen Journalism’s legal adviser. “If you can’t see how 80% to 90% of the water is being used, then you will never be able to say whether you’re using water efficiently or not.”

Ditch-inventory projects have the support of many water-user groups and, in recent years, have been done in several Western Slope river basins and sub-basins: the Yampa, the Eagle and the Colorado. Agricultural groups say they are necessary to assess the needs of irrigators and connect them with resources should they want to improve and upgrade their infrastructure. Environmental organizations say they have value because the more improvements there are to irrigation efficiency, the more water that can be left in the stream to the benefit of the ecosystem.

In some ways, the issue boils down to whether one sees water as a private property right or a public resource. In Colorado, it’s both. The right to use water is treated as a private property right. People can buy and sell water rights as part of a real estate transaction and change what the water is allowed to be used for, as long as a water court approves. And to maintain a water right’s value, the water must be put to use.

But the right to use water isn’t the same as owning the resource itself, which belongs to the people of Colorado. Ransford said there’s an obligation for water users to use it responsibly and efficiently.

“To say nobody has a right to see how it’s being used when it’s a public resource, there’s a conflict there,” he said. “We all own the water. It’s a public good.”

Middle Colorado ditch inventories

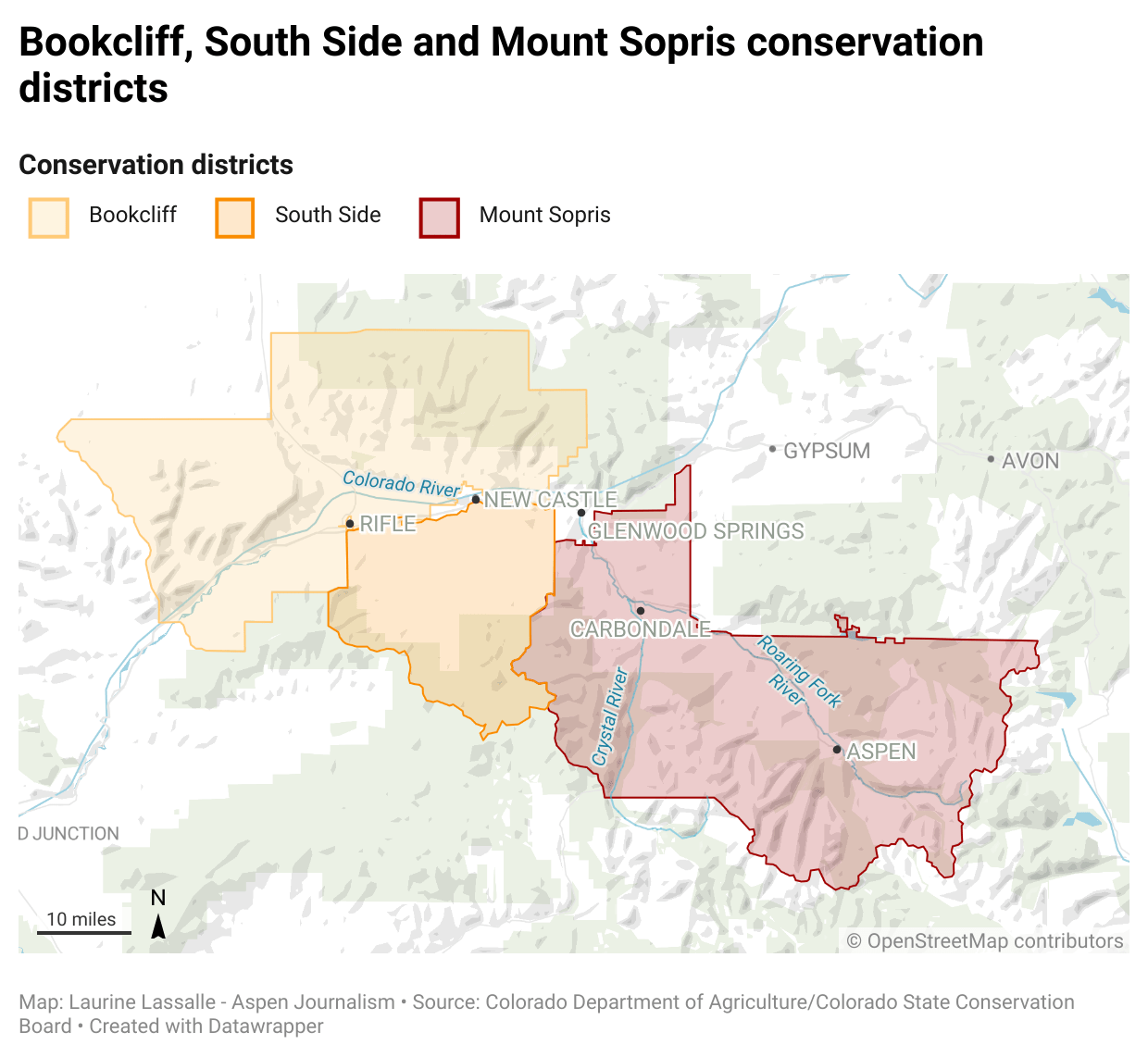

In 2018, the Colorado Basin Roundtable recommended approval of a $100,000 funding request from the Book Cliff, Southside and Mount Sopris conservation districts for an agricultural water plan for Garfield County. It was part of a larger stream-management plan, undertaken by the Middle Colorado Watershed Council. The 2015 Colorado Water Plan calls for developing stream-management plans on 80% of rivers in the state.

The funding for the agricultural portion — part of an overall $330,000 budget for the plan — was approved by the Colorado Water Conservation Board, the state entity charged with protecting and developing Colorado’s water.

As part of the agricultural water plan, the conservation districts hired Rifle-based Colorado River Engineering to conduct ditch inventories, which provide water rights owners with an overall assessment of their diversion infrastructure, measuring devices and conveyance channel. The study focused on ditches that have old and large water rights — prior to the 1922 Colorado River Compact — and carry more than 10 cubic feet of water per second. The goal is for owners to use the inventory as a tool to prioritize projects on the ditches and aid in securing funding for future ditch improvement projects.

In October, the conservation districts submitted to the CWCB a final report, which includes a broad overview of the project. The 59 individual inventories completed were not included in the information submitted to the state, although each water rights owner got a copy of their own inventory. It is not clear which ditches across the three conservation districts were inventoried as part of the project.

Aspen Journalism began making inquiries about seeing the completed inventories in March, and the conservation districts made one inventory available: the study of the Schatz Ditch on Dry Hollow Creek near Silt, which irrigates 69 acres of grass pasture. The ditch has two water rights, which date to 1965, and are decreed for 2.5 cfs each.

The 44-page inventory includes information about the water rights associated with the ditch, publicly available diversion records from the state Division of Water Resources database, and many pages of historic decrees and documents associated with the ditch. It does not include names of ditch owners, water rights owners or water users.

It lists main concerns as a lack of current diversion records after 2001, overgrowth of vegetation and unstable soils near the end of the ditch. Potential treatment includes removing overgrowth, routine maintenance, lining or piping the ditch, and self-reporting diversions to the Division 5 Water Resources office.

The inventories are a good way to maintain institutional knowledge and keep track of historic ditch information when there is a change in ownership, said Emily Schwaller, manager of the conservation districts. She said the districts made the Schatz inventory available because the owner or owners gave permission for the information to be public, but she declined to disclose who the owners are.

“Our hope is that these binders are living documents that get updated and maintained by the ditch companies and owners,” Schwaller said in an email. “These inventories give the (ditch owners) a baseline of the condition of the ditch and are a start of the background of the ditch that will be used by future generations and ditch owners.”

CORA request denied

But neither the CWCB nor the Colorado Basin Roundtable has a policy that allows the public to have access to the inventories, even when public money is used to fund their creation.

In May, Aspen Journalism submitted a Colorado Open Records Act request to see the rest of the 59 inventories. The conservation districts denied the request, saying a federal law supersedes the state’s sunshine laws. Because the conservation districts partnered with the National Resources Conservation Service on the inventories and a federal law protects personal and geospatial information of property owners who work with NRCS, the districts said they would have to review what information could be released and redact any private information.

CORA lets the public inspect records of state and local government entities — unless inspection is prohibited by a state law or a federal statute or regulation. The 2008 Farm Bill may prohibit the release of information regarding agriculture practices.

“It’s not clear what information in the ditch inventories can and cannot be provided to the public under the 2008 Farm Bill,” said Jeff Roberts, executive director of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition, a nonprofit group that works to ensure the transparency of state and local governments by promoting freedom of the press and open access to government records. “The conservation districts should explain this in more detail, and the best way to do that is with an example ditch inventory and a log that describes why each redaction is required by federal law.”

After working with the boards to get a cost estimate for redacting, Schwaller on Dec. 13 provided a cost estimate of nearly $2,200 for redacting the engineering reports and almost $16,400 for the engineering reports and records. Aspen Journalism has asked Schwaller for a cost estimate for redacting the Schatz Ditch inventory to see an example of what information would be left after redacting and whether it would be worth it to pay for the rest of the documents with redactions. Schwaller had not replied to multiple requests as of press time.

Sara Leonard, director of CWCB marketing and communications, said that it would be inappropriate for the state to ask for a ditch owner’s personal information and that the state and roundtables support property rights and landowner privacy.

“The state’s role here is to provide funding and help identify the best projects, as supported by the basin roundtables,” Leonard said in an email. “We look for collective results and analysis of individual data to show the success of a project, but we don’t require individual data points as they are not needed by the state (in this case, individual ditch inventories).”

Dylan Roberts, who represents Eagle and Routt counties in the Colorado legislature and sits on the Water Resources Review Committee, said it sounds like the inventories have incredible merit and could be useful. If the state has decided to put money behind them, then the public should have access to them, he said.

“As a matter of principle, if public money is being used, there absolutely should be some level of transparency and public access to any data or information that is generated from these surveys,” he said.

Summary outlines ditch problems

According to the final report from the three Colorado conservation districts submitted to the CWCB in October, 59 ditches were inventoried on the section of the Colorado River and tributaries from Glenwood Canyon to De Beque. The individual inventories include a summary of the water rights, diversion records, irrigated acreage, a list of concerns, potential treatments and funding opportunities to address those concerns. This information is withheld from public view.

The report listed main areas of concern, including erosion prevention; seepage; aging infrastructure; routine maintenance; diversion/lateral structural improvements; phreatophytes, which are sometimes-invasive, water-sucking vegetation with deep roots; and bank stabilization.

According to a report produced last year as part of the Middle Colorado Integrated Water Plan on agricultural water use, engineers recommended phreatophyte removal for 71% of the inventoried structures; piping or lining ditches for 55% of them; and bank stabilization for 51%. Improvements to measuring devices were recommended for 35% of the ditches inventoried.

Though broad generalizations, these findings in the summary report and the Middle Colorado plan hint at widespread issues with the region’s irrigation ditches, headgates and canals.

“We have a huge issue with aging infrastructure here on the Western Slope,” said Jason Turner, chair of the Colorado Basin Roundtable and senior counsel with the Colorado River Water Conservation District. “There are billions of dollars’ worth of projects in the Colorado basin alone, and I bet that doesn’t even scratch the surface.”

Privacy maintained

These types of inventories have a history of being shielded from public view, even though they are paid for with state grant money.

In 2016, the Eagle County Conservation District conducted what it called an irrigation-asset inventory of 25 ditches within the district’s boundaries. It was funded with a $54,000 grant from the CWCB. Although a summary report of the findings was made public, the 25 individual binders with information specific to each ditch went to the ditch owners and were not, despite a request from Aspen Journalism under CORA. The summary said irrigators in the district were dealing with problems such as rusted, leaking and clogged culverts, unstable headgates, sinkholes and erosion.

Proponents say the promise of privacy is often key to getting irrigators to participate in these studies. Maintaining privacy is important for irrigators because they may not want to invite what they feel is unfair scrutiny — and, perhaps, criticism — of their operations.

“I think the only way these guys are going to participate in these kinds of things is if they feel like their information is not going to be shared everywhere,” Turner said. “They recognize that they own and use the lion’s share of water in Colorado, and it just seems like they feel heavily scrutinized for what they feel is their best ranching practices for their piece of property.”

The report from the inventories in the Book Cliff, Southside and Mount Sopris conservation districts said this culture of privacy is a challenge. Earning the trust of water rights owners so that they would give their permission to do the ditch inventories took additional time and was a larger factor than originally anticipated.

“Another noteworthy obstacle was obtaining permission from water and landowners to walk the ditch and develop the inventories,” the report reads. “This ranged from not having up-to-date records of owners, neighbor conflict and a general distrust in allowing outside eyes on the properties.”

Yampa River assessments

On the Yampa River, environmental organizations have acknowledged the potentially problematic lack of transparency that comes from paying for private inventories with taxpayer money and have taken steps to skirt the issue by directly funding the studies themselves. Trout Unlimited and The Nature Conservancy paid nearly $68,000 to do an assessment of diversion infrastructure on the Yampa with the goal of identifying places for multibenefit projects.

“We were aware of the Eagle River situation, but there are a bunch of reasons (that environmental groups) took the lead on the assessment,” said Brian Hodge, northwest Colorado director for Trout Unlimited and the environmental representative to the Yampa/White/Green Basin Roundtable.

Of 45 irrigation structure owners who participated in the study, 36 opted to make those reports public. The other nine chose to keep their reports confidential, citing disagreement with the structure assessment or discomfort with the process. A few structure owners did not respond to outreach after their report was delivered.

In a final report, produced by Wilson Water Group and JUB Engineering, the structures were scored based on the opportunities for improvements for four categories: current use, fish passage, recreational boating and river health. Each category had a maximum score of 5 for a total possible structure score of 20. The higher the score, the greater the opportunity for a multibenefit improvement project. The Lower Yampa reach of the river had the most room for improvement overall, with a total score of nearly 8.

Improvement projects not publicly tracked

It is also not always clear whether these studies actually result in improvements to irrigation infrastructure, which is listed as an end goal. In some cases, neither the conservation districts nor the funding organizations keep track of how many subsequent projects come about as a direct result of the inventories.

And unless the ditch owner comes back to a granting organization, such as the roundtable, with a request for funding, there is no way to know whether ditch owners actually use the inventories to improve their operations, especially if they pay for upgrades out of their own pocket.

Turner said the roundtable would have no way of knowing unless an irrigator referenced the inventory in a subsequent grant application.

Leonard, the CWCB spokesperson, said she is not aware of anyone tracking projects that come out of the inventories.

“Again, potential projects that will likely come out of the inventory assessment will hopefully lead to multipurpose/multibenefit projects that can be supported by CWCB funding, but we don’t mandate projects as a result of investigations we fund,” she said in an email.

The report from the Book Cliff, Southside and Mount Sopris conservation districts said ditches with completed inventories have applied for funding from several different sources: the Colorado River Water Conservation District, the state of Colorado, National Resources Conservation Service, and the conservation districts’ cost-share program. Water rights owners have also hired engineering firms to complete the recommendations in the inventories and used the inventories while requesting letters of support from county commissioners, according to the districts. But conservation district representatives did not have a count of exactly how many projects have come about as a direct result of the inventories.

Eagle County Conservation District also does not have a count of projects that resulted from their 2016 inventories, but there is at least one. The Highland Meadow Estates at Castle Peak Ranch Homeowners Association in Eagle County received $25,000 in state money to improve the Olesen Ditch by installing a pipeline.

Mount Sopris Conservation District board member Cassie Cerise owns a ranch outside of Carbondale. She did not participate in the ditch inventory project, but she thinks the inventories were useful for ditch owners and she expects resulting projects to trickle out over the next few years.

“First, the issues can be identified, and second, they can find out about all the different programs that are offered as far as cost share and all the things that could help implement a fix,” she said.

Privacy was a roundtable topic

The issue of privacy for landowners when it comes to these ditch inventories was a topic of discussion at the Colorado Basin Roundtable meeting in October. Some said the public may be critical of how ditches are operated.

“There may be reasons why a landowner may not want the public looking at a ditch on their property,” said Carlyle Currier, a rancher in Molina who is president of the Colorado Farm Bureau and has a seat on the roundtable. “It certainly opens the door to some mischief.”

Ransford, the recreation representative to the Colorado Basin Roundtable, said that since water is a public good, there should be a public means of funding irrigation-improvement projects.

“I’ve long thought what we should do is pass a special-district kind of a tax to pay to modernize irrigation structures,” he said. “I don’t think the irrigators should have to do it. It’s expensive. But if we had a public source of funds dedicated to this, to me, that is the bigger picture.”

Some say the end justifies the means. Richard Van Gytenbeek is the environmental representative to the Colorado Basin Roundtable. In his work as Colorado River basin outreach coordinator for Trout Unlimited, one of his goals is to work on collaborative efforts with the agricultural community to keep more water in rivers. He said if the inventories can help do that by facilitating irrigation-efficiency projects, then he doesn’t have a problem with the information remaining private. Trout Unlimited often works with irrigators on projects that benefit the landowner as well as fish and stream health.

“I’ve seen some ditches that are just horrendous, and if we were able to get in there and fix them, people wouldn’t have to take out nearly as much water,” he said. “We are trying to think of ways to have (water) never leave the channel in the first place. Getting people to collaborate and cooperate, it’s the linchpin.”

Aspen Journalism collaborates with The Aspen Times on coverage of water and rivers. This story ran in the Feb. 6 edition of The Aspen Times and the Feb. 7 edition of the Vail Daily.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.