By Patrick Cone

The sun sets on the Grand Canyon, sending the inner gorge into shadow as the buttes catch the red light. Tourists on Mather Point watch the spectacle, content with absorbing nature’s most awesome show. Deep in the canyon, the Colorado River roars, fed by mountain snowmelt. In the side canyons the springs, seeps, and streams nurture birds and trees and wildlife in this arid landscape. A mile up, elk shedding their winter coats graze the dry Ponderosa pine forest for green shoots.

But after sunset the visitors disperse for the night, headed off for their campgrounds, dinner, and lodging. While some stay within the park, many head just outside of the South Rim gate to the town of Tusayan, Arizona, with its rows of restaurants, hotels, shops, theatres, and museum.

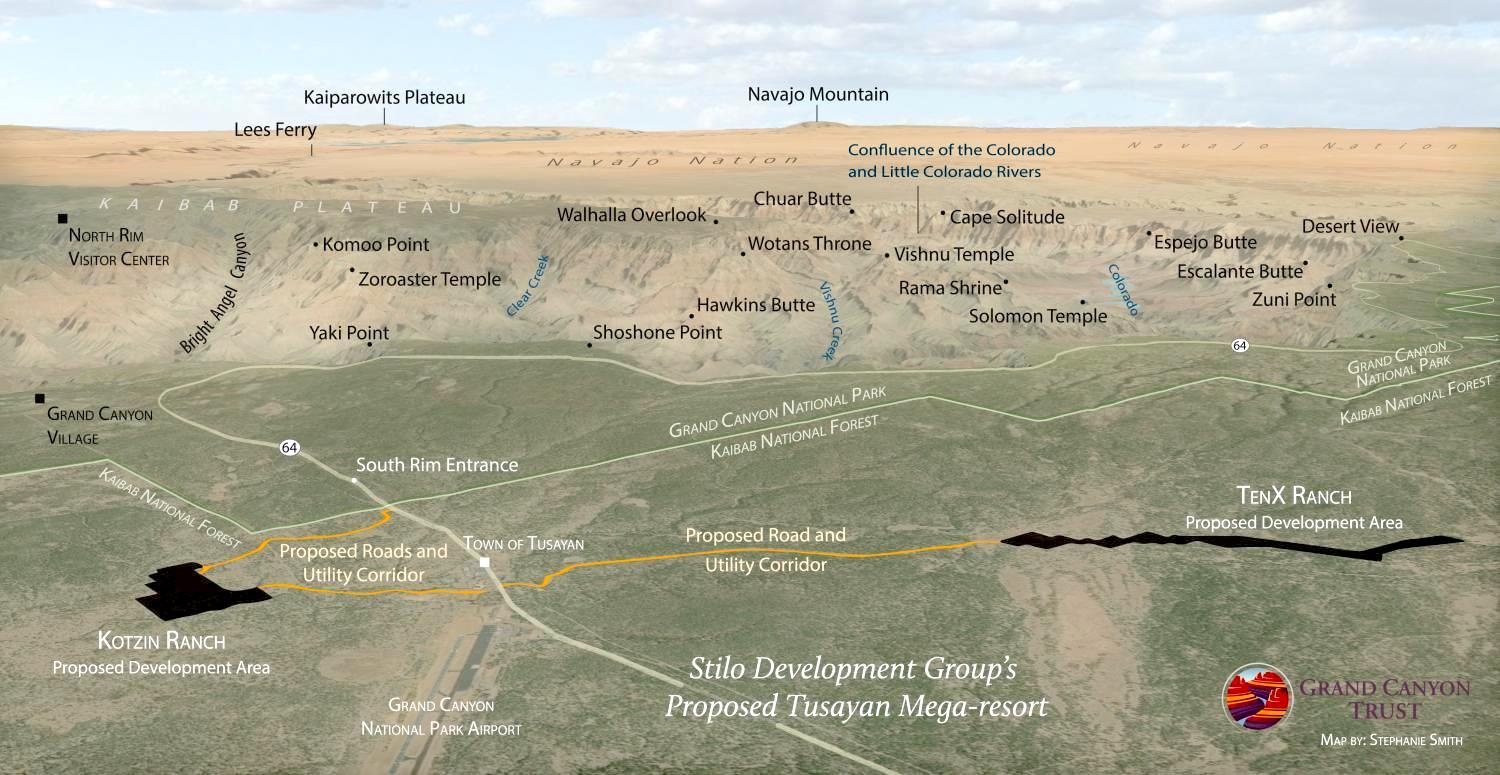

But Tusayan’s character could potentially boom, with thousands of new homes, employee housing, and millions of square feet of commercial space if Italian developer Stilo gets approvals. Rezoned in 2011 from open space to commercial, their two large inholdings (195 and 160 acres) within the Kaibab National Forest are accessed by two unimproved forest roads, and for Stilo to build they need an easement from the U.S. Forest Service to use these gravel roads for power, sewer lines, natural gas, and communication infrastructure. For some it’s an opportunity, and for others it could change the town forever.

Opponents say the project would threaten roads, wildlife, and even the night sky itself, not to mention the lifeblood of the South Rim: water. Proponents point to economic development to serve an ever-increasing number of visitors.

Development Seems Inevitable

There’s no doubt that visitation to the Grand Canyon is booming, with nearly 6 million visitors in 2019. Despite a partial park closure in 2020 due to Covid-19, nearly half that many came to see this wonder of the world. As things return to a near normal in 2021, numbers are once again expected to peak, stressing what are already limited services in Grand Canyon National Park and nearby Tusayan.

Tusayan was homesteaded in 1918 (the year before Grand Canyon became a national park) and there was very little development until the late 1940s; in fact, Tusayan was only incorporated as a town within the last decade. Today there are about 600 year-round residents, working primarily in the service industry at the lodges, hotels, restaurants, and shops.

In the summer, the airport’s a busy spot too. A half-dozen, orange jet helicopters buzz back and forth, and come and go, like a nest of hornets. A $37 million airport expansion will bring in even more visitors by plane as well. Today, summer traffic backs up for miles at the park gates, parking lots are full, shuttle buses are packed.

Stilo’s initial request for a permit from the Kaibab National Forest for a road easement was refused in 2016, even before any environmental review, because “it fails to meet minimum requirements for not interfering with the use of adjacent federal lands.” The Forest Service reviewers were concerned of the impact not only to Grand Canyon National Park, but to tribal lands as well. The developer’s second proposal, filed last year, however, is not well-defined and will likely undergo a complete Environmental Impact Statement.

Clarinda Vail is the mayor of Tusayan, and a third-generation owner of the Red Feather Lodge, and she too has questions. She’s been involved with the town forever, and exudes energy as she gives us a tour of the area.

Tusayan Mayor Clarinda Vail is anxious about how the project could impact her town/Patrick Cone

“Depending upon the entity that you talk to in the proposal, it’s anywhere from about 3 million square foot of retail,” she said, “and anywhere from one to 5,000 hotel rooms. And I just say that because they’ve talked about phasing. And so, it really is unknown as to what could be built up to. Those are kind of the maximums that it could be built up to … There have not really been specifics proposed.”

But on everyone’s mind is water. Where will it come from? Tusayan itself has an extensive reclaimed water system, and in this desert every drop counts.

Groundwater wells are thousands of feet down, and even the national park relies on an antiquated, failing pipeline that brings water from a thundering spring pouring out of the North Rim to the South Rim to slake the tourists, employees, and year-round residents. Replacing that line, according to Grand Canyon Superintendent Ed Keable, will cost “around $100 million.”

Stilo has offered some preliminary thoughts on their water sources, including trucking in water for the commercial spaces and drilling new wells for the residential areas. But no specific sources have been proposed.

“I think water is always the biggest topic of any discussion in our region,” said Mayor Vail. “How do we all know we’re going to provide our communities water for hundreds of years to come? Not for 10 years down the road, but for long term. And where we are here, we have to be really environmentally sensitive, with regards to our water, because of what it does to the seeps and springs, and for the Havasupai people, and for our neighbor (the park). It’s an incredibly important topic to be discussing. And we’re in a 1,200-year drought. You know, water has always been the gold of the West. And it’s only going to get more so as we go on here with more population.”

Roger Clark is the past director of the Grand Canyon program for the Grand Canyon Trust, and has similar questions: “Where are they going to get the water, which has direct implications to springs in the Grand Canyon? There is water down 3,000 feet, and hydrologists in the park have information that the water Tusayan is using is directly affecting the springs in the canyon. For the Havasupai Tribe, their sole source of water might be threatened by the existing wells. If they (Stilo) put up thousands of new residences, and those residences are dependent on groundwater, it really could be a death sentence for Grand Canyon springs.”

The Havasupai Tribal Council went on record in 2019 opposing the project, writing Forest Service officials that it is a threat to “the Tribe’s primary and near-exclusive water source — the Redwall-Muav Aquifer — and the Tribe’s sacred places on the Coconino Plateau.”

“The Town of Tusayan currently draws on the Redwall-Muav Aquifer for its water supply, and its existing demands for water are already jeopardizing flows into Havasu Creek and, by extension, the Tribe’s livelihood,” the letter went on. “The Stilo proposal threatens to further strain the limited supply of groundwater from the Redwall-Muav Aquifer that the Tribe depends upon for its cultural identity and continued existence.”

Groundwater Nourishes Grand Canyon

While not visible from the rim, there are plenty of springs, streams, and creeks within the canyon, and wildlife and vegetation rely on these water sources for survival. Some of the springs gush like a firehose from the cliff, such as Vasey’s Paradise in Marble Canyon and Thunder River, while hanging gardens and small creeks abound. They all water the ferns, columbines, and monkeyflowers, as well as the deer, big horn sheep and birdlife.

David Kreamer has spent three decades studying these water sources in the canyon. He’s a professor of hydrology at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas, and he’s concerned about development, and water, on the South Rim.

“When I started back 30 years ago there was only one deep well….and now there are several in Tusayan that draw water,” said Kreamer. “There are more and more wells going in. In my opinion, it’s not a question of if spring flow is going to be diminished. It’s a question of when. And so, I think that there’s evidence that there is a connection between where people would develop and impacts on the Grand Canyon springs.”

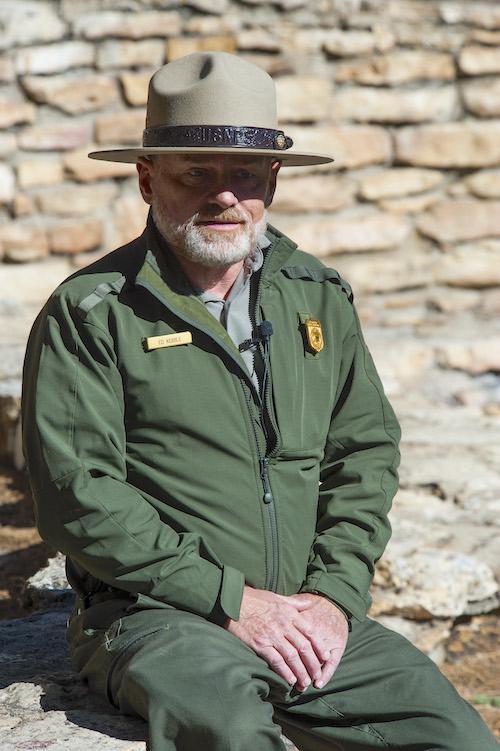

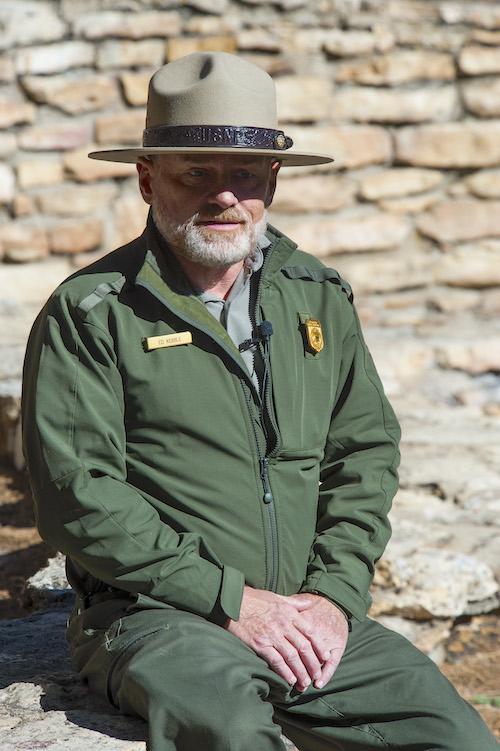

Grand Canyon Superintendent Ed Keable wants to know how the project would impact groundwater flowing into the national park/Patrick Cone

Superintendent Keable is watching the process carefully.

“That development project has been in some fashion in the works since 1992,” he said. “The Forest Service is doing what it needs to do. It’s reviewing that proposal under the (National Environmental Policy Act) process, and the Forest Service has reached out to the park. We are working with the Forest Service to provide what input we will provide. It’s still early in the process. Frankly, we need more information. And one of the pieces of information that I’m going to be interested in is what are the impacts on water to the area? So that’s going to be a key source of information for me as I work with my science staff to determine the impacts of that proposal on the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River Basin.

Andy Jacobs, of the Policy Development Group, is a spokesman for Stilo. He said the company has downsized the development in the latest proposal by 33 percent and pledged not to use groundwater for its commercial components. They’ve also donated 20 acres within the project to construct affordable long-term housing. Currently, people working in or near the park face few options for housing, and much of it is either employer-owned trailers or modular homes. But there’s no assurance about how affordable the new housing will actually be.

“The town council and planning and zoning board have both approved the broadly planned community district zoning several years back,” Jacobs said. “Stilo technically has the zoning approval, but the inholdings are within the forest. There are a lot of uncertainties for a path forward. It’s been a holding pattern lately, though they’ve owned these (parcels) for almost 30 years now. We’re interested in working with people.”

How Much Development Is Needed?

There’s no doubt that with six million visitors annually, and growing, that the area is ripe for some sort of new development. And, according to Stilo, people are looking for things to do on and next to the South Rim when they’re there.

The scale of the proposed development is still overwhelming to some, even with the proposed reduction in their new application. Alicyn Gitlin, the program manager for the Sierra Club, Grand Canyon Chapter, is frank in saying the project is just too big.

“It’s a massive development,” she said.

Problematic, Gitlin went on, is that while Stilo claims its latest proposal reflects a 33 percent reduction in development, “they never really told us what they were planning.”

“So, you know, a 33 percent reduction of ginormous is still ginormous. So we’re pretty much concerned with everything. We’re concerned with the light, the noise, the litter, the wildlife impacts, the traffic, bringing more multi-day visitors to Grand Canyon where they’re going to be putting stress on already aging infrastructure,” she said.

“We’re worried about the cultural impacts of more people being in the forest there. We’re worried about the loss of campsites that people are using (in the Kaibab Forest) when they’re visiting the park. You have to remember that this community relies on others for all of its resources. It doesn’t have a clinic, it doesn’t have a cemetery, it doesn’t have a trash dump. It doesn’t have its own law enforcement,” Gitlin pointed out. “We recognize that there is a need for housing that is not employer-owned in Tusayan, and that’s not what we’re trying to stop. The scale of this development is completely out of step with what is needed. It’s going to create a bigger workforce housing issue because they’re going to need to have workforce to run all these things. And where are those people gonna live?”

As the summer season begins, and the crowds descend on the town and park, the project has divided the town.

“Yes, absolutely. It’s been very controversial,” Mayor Vail said while looking over the TenX Ranch acreage. “I’m always proud of our community, like our school project, our sports complex. And so, I do love that we can disagree on certain subjects. We all come together on the things that are important and move together wonderfully. So yes, it has divided. But we still know when to come together on things. It’s just the right thing to do.”

Yet, Tusayan depends on tourism for its existence, and there are opportunities for economic development and there will be growth. The Grand Canyon is a special place, whether seen by a rowboat on the Colorado River, hiking down the trails, on aerial tours or just watching the light change on this magnificent landscape.

Mayor Vail understands that change is coming.

“Every community wants economic development,” she noted. “And you get to the point where you have to ask yourself, is this type of economic development worth the character and the soul of our community?”

This coverage was made possible through grants from the Society of Environmental Journalists – Fund For Environmental Journalism and the Water Desk at the University of Colorado.