By Jerd Smith

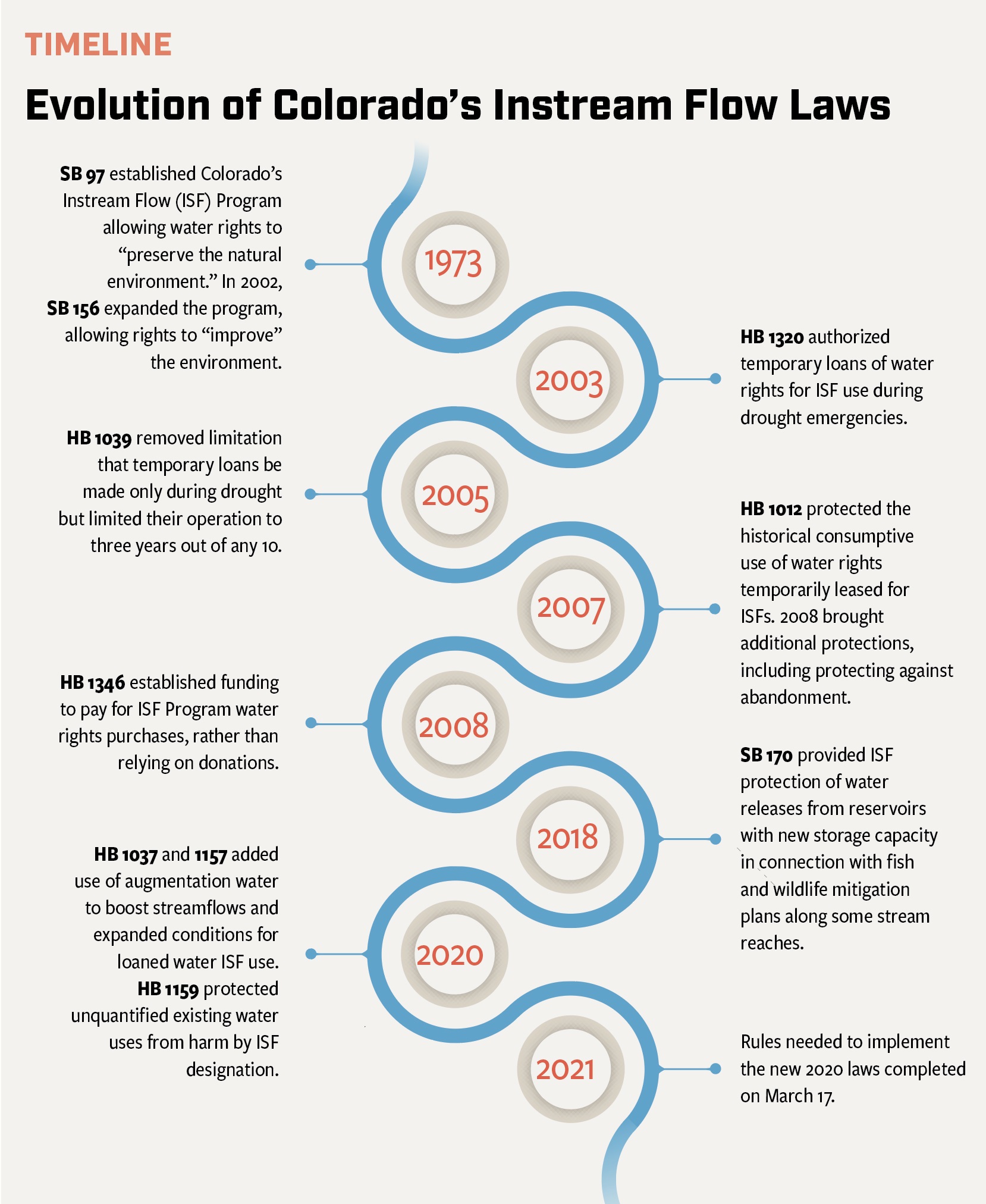

In 1973, Colorado broke new legal ground by establishing water rights solely for the protection of streams, fish and wildlife. Prior to that, water could be diverted only for things like farming, manufacturing and residential water use.

When the state moved to establish these environmental water rights, it was one of the first states in the American West to do so.

This year it will dramatically expand that ground-breaking effort as three new laws, passed in 2020, take effect. One involves the use of temporary water loans, a second adds protection for ranchers who divert water for cattle in stream segments where special environmental flows have been designated, removing an important obstacle to establishing new environmental flows, and a third creates a new tool for environmental flows once only available to cities and farmers.

Zane Kessler, director of public affairs for the Glenwood Springs-based Colorado River Water Conservation District, said the changes represent an important evolution in protecting environmental flows while balancing the needs of Colorado’s ranchers and cities with those of the environment.

“Good policy helps us evolve to meet changing needs and priorities over time,” Kessler said.

How the new laws work

The expanded temporary loan program authorizes emergency loans and allows loans of water for five years in three separate 10-year periods. Previously those same loans could be used only for three years in a single 10-year period.

This provides relief for several regions, including the Yampa River Basin, where an instream flow loan had been used to its fullest extent under the old law, even though drought has continued to harm the Yampa River. The new longer-running loan program will provide critical flows to the river.

The stock water law, though it doesn’t directly add water to streams, writes specific rancher protections into law, paving the way for more stream segments to be considered for the program.

And the third law, which advocates believe may have the most significant impact of the three, allows something known as an augmentation plan to incorporate environmental flows to help protect streams.

Advocates, such as the Colorado Water Trust, a nonprofit that spearheaded the new approach, say the tools can be used as templates across other river basins, where older water rights are already spoken for.

“In the long run, this could be more impactful,” said Kate Ryan, an attorney for the Colorado Water Trust.

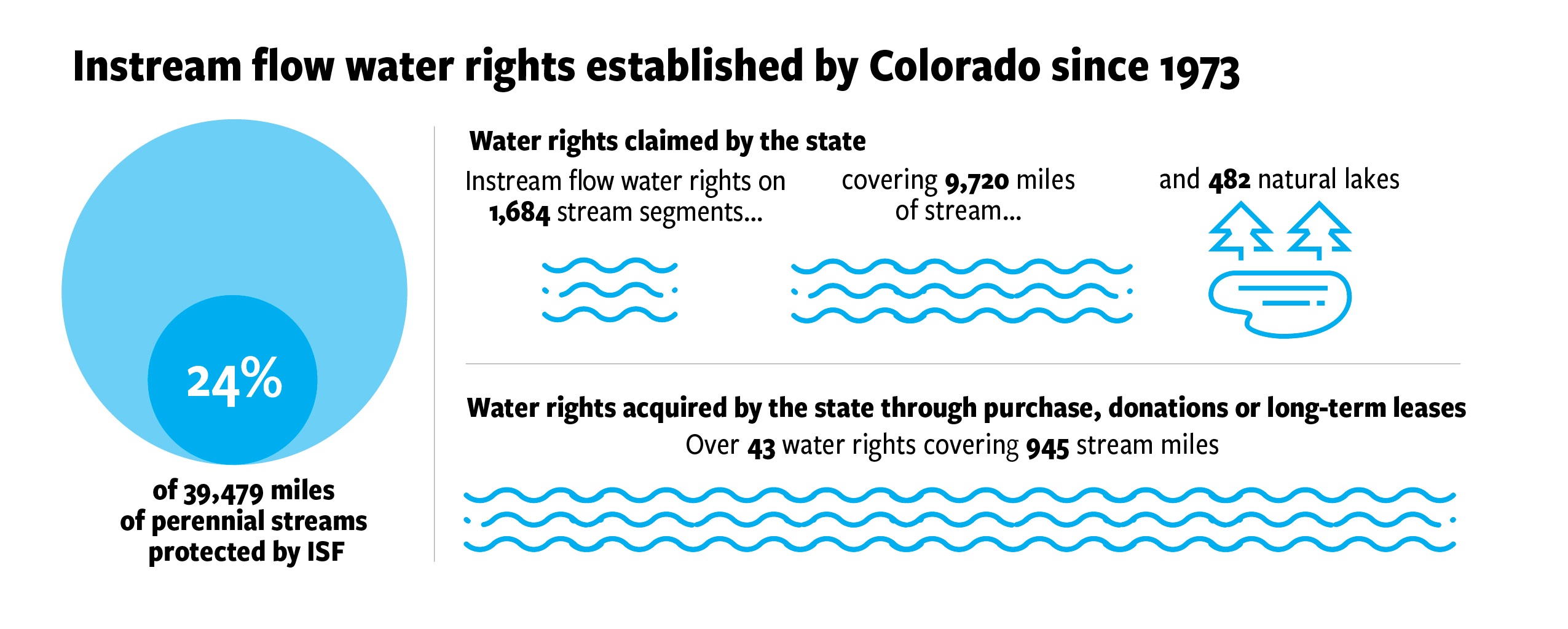

Across Colorado nearly 40,000 miles of streams flow year-round and, as a result, have the potential to receive protection under the state’s Instream Flow Program. To date, the state has been able to establish environmental flows on nearly one-quarter of these, according to the Colorado Water Conservation Board, which manages the program. The CWCB is the only entity legally allowed to hold these environmental water rights in Colorado.

Who gets to choose

Anyone can go to the CWCB and ask that it protect a certain stream segment, but whether it’s a member of the public, the U.S. Forest Service, or The Nature Conservancy, the entity must be able to show that there is enough water in the stream to support a new water right. They must also show that, by decreeing an instream flow on that segment, the stream’s existing conditions will be preserved or, where possible, improved.

To accomplish this, extensive engineering and measurements must be conducted. Once an instream flow case has been researched and documented, the state must go to a special water court to have the right legally established. The court must also hear any challenges that other water rights holders on the stream segment may raise if they fear their own water rights could be harmed. The process often takes several years to complete.

Linda Bassi oversees the Instream Flow Program for the CWCB.

“It’s difficult because there are a lot of competing interests for water,” Bassi said. “On some streams, if the state wants to obtain a water right to protect flows there are a lot of other entities with water rights that may feel threatened. Or there are other entities that might have plans to develop a water right on that same segment who are made uneasy by the fact that we are coming in to establish one [an instream flow water right].”

In Colorado, water rights follow what’s known as the Prior Appropriation Doctrine, or “first in time, first in right.”

That means that a water right claimed in, say, 1894 will get its water before one claimed in 1905 during periods of drought, when there isn’t enough water for everyone who has a right to water in a given stream.

A late start

Because the state environmental program was established 100 years after water users had claimed much of the water in the states’ rivers, the water rights the state has managed to claim are very young, or junior to other more senior rights. That means that in drought years, when they are needed the most, these rights frequently go unfulfilled.

As a result, the state has changed its laws to allow older, senior water rights to be loaned or donated to the state. When it has enough money, the state can actually purchase older water rights that are more likely to receive water during dry years.

When proponents of the 2020 expansion went to lawmakers in 2019 to seek support for the new laws, they faced significant opposition from agricultural interests and cities. It took months of negotiations to craft the bills that finally won near unanimous bipartisan support at the Colorado State Capitol in 2020.

Getting to “yes”

The Colorado River District represents 15 Western Slope counties, many of which are heavily dependent on ranching. Historically any efforts to add new water rights for protecting streams have been viewed with deep skepticism.

This time was no different, Kessler said, but rural lawmakers were able to add enough protections into the new laws that the district’s board ultimately came out in support of the expansions.

One important measure gives the state engineer, Colorado’s top water regulator, the authority to oversee ranchers’ rights to their so-called stock water.

“During the winter months, ranchers with an irrigation water right [tied to] the summer season will often pull small amounts of water from the stream to keep their animals alive,” Kessler said. “With that [protection] in hand, we became a lot more malleable about how we approached the Instream Flow Program.”

A third part of the expansion, allowing the use of augmentation plans to restore environmental flows, could be among the most important part of the expansion effort, according to Ryan.

Farmers and cities have long used augmentation plans to repay the river when they divert out of turn. Now under the new law, this same tool can be used to help streams.

On the Front Range, for instance, the first environmental augmentation plan is getting ready to launch, with the cities of Fort Collins, Thornton and Greeley offering up water they own and already store under an existing augmentation plan. These “seed” flows will be added above various stretches on the Poudre River that dry up every year. As the new water flows downstream, it will restore habitat for fish and wildlife, and eventually travel down to a segment of the river that these cities are presently legally required to restore.

And though most environmental water deals require individual trips to water court, an expensive, time-consuming process, the new law allows existing augmentation plans to be used, which means proper quantities, times of diversion, and water right dates are already in place.

“There are those who believe that prior appropriation as it is practiced in Colorado is too rigid,” said Sean Chambers, Greeley’s water resources manager. “But I think this is an example of how we can use existing statues, tools and programs to meet the needs of municipalities, irrigators, agricultural interests, and the ecological and recreational needs of the river. And it’s a template that can be used in other [river] basins.”

Looking ahead

How many more miles of streams could still be protected under the Instream Flow Program isn’t clear, according to Bassi, because the state’s priorities and its ability to buy water rights change.

But every year there are victories.

For decades, fish experts believed that a certain line of endangered cutthroat trout known as the San Juan lineage cutthroat had been extinct. But then they discovered them in a remote part of the San Juan River Basin and, last year, the CWCB was able to establish an instream flow on a critical stream segment there, helping ensure the endangered fish will survive.

“Priorities change, whether it’s [water for] a gold medal fishery, which helps the recreation industry, or to protect a declining species. We don’t have a set quota. We’re just trying to help these organizations achieve their goals through our program,” Bassi said.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.