By Caitlin Coleman

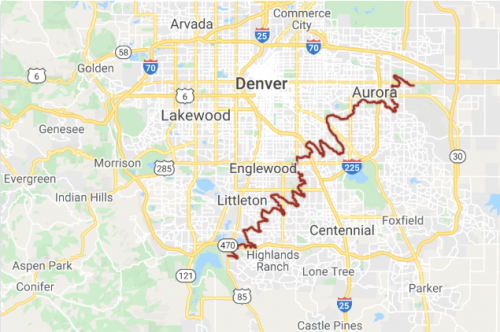

Infrastructure built more than a century ago still endures, but some of Colorado’s old irrigation ditches have been repurposed to meet the moment. The High Line Canal—a 71-mile-long former irrigation conveyance turned greenway and stormwater filtration tool—winds its way through the Denver metro area as an artery of infrastructure boasting a story of adaptation.

The canal, built in the 1880s to move irrigation water, was purchased by Denver Water in the 1920s. But the metro area changed around it. By the 1960s, people were sneaking onto the service road alongside the ditch and using it as a walking trail, says Harriet Crittenden LaMair, executive director of the High Line Canal Conservancy, a nonprofit working to preserve, protect and enhance the canal.

By the 1970s, municipalities and special districts began negotiating with Denver Water to allow residents to legally enjoy the tree-lined trail. While this opened the canal up to public enjoyment, it also divided it through a series of leases and use agreements. “[The public] saw it as a greenway but it was being cared for as a utility corridor,” Crittenden LaMair says.

So sparked the development of a working group, and eventually the Highline Canal Conservancy, to create a larger, unified vision for the waterway. “In urban areas, people are rethinking the uses of old infrastructure that has outlived its original purposes,” Crittenden LaMair says. “Parks advocates are working with utilities and thinking, ‘Wow, what additional benefits can be seen from this infrastructure?’”

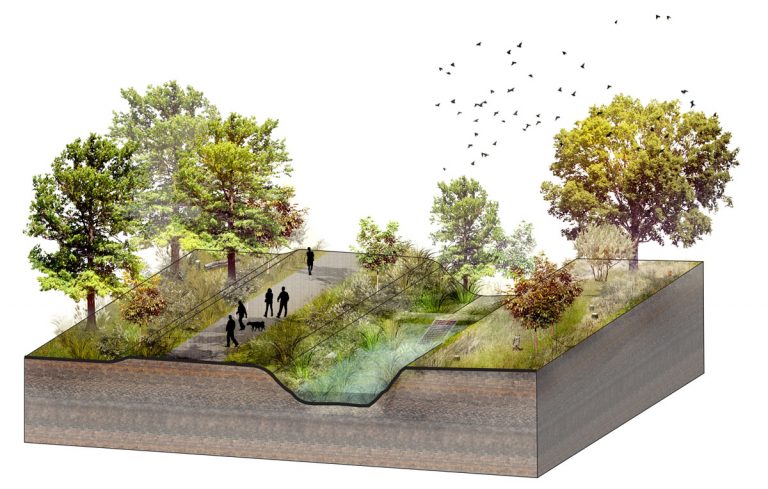

With the public using the trail as a recreational resource, Denver Water has been weaning customers off of water delivered through the canal, having them instead rely on more efficient conveyances. While there are still a few dozen customers receiving water via the High Line Canal, they will switch to different sources within the next few years. In the meantime, the canal will capture and filter stormwater. “It’s amazing that parts of the actual infrastructure built in the 1880s can be used, with modifications, for stormwater management,” Crittenden LaMair says.

The Conservancy’s 15-year plan for the canal, completed in 2018, comes with a price tag of more than $100 million in improvements, including the stormwater management infrastructure, underpasses, interpretive signage, and more. Work will be incremental, but four individual stormwater projects are already underway to filter runoff before it makes its way to receiving streams, helping municipalities and special districts meet their stormwater discharge permitting requirements.

That stormwater benefit is even lessening the new infrastructure that some developments and cities would have had to build, says Amy Turney, director of engineering for Denver Water and the utility’s stormwater lead on the High Line Canal work. “As development and roadway projects get designed close to the canal, developers and cities are realizing that using the canal is a better option than having to build new detention ponds and storm sewers.’”

Work on the High Line Canal hasn’t been without its challenges. Public perception has been high on that list with people cherishing the canal as a recreational greenway while the utility was using the canal as a piece of water delivery infrastructure.

“We had a maintenance road that turned to a path and [neighbors] didn’t want maintenance trucks anymore. There’s been no shortage of public ownership. This is their backyard—literally,” Turney says. But it will be worthwhile in the end. “The long-term success of the infiltrated stormwater helping the greenway prosper and improving receiving stream health is a legacy for us, as well as an amenity throughout the Denver metro area that thousands enjoy every year. We’re really proud of it,” she says. “Anyone who hears about this and cares about water gets excited about how we are saving water, and simultaneously using water for the best purposes.”

Caitlin Coleman is the Headwaters magazine editor and communications specialist at Water Education Colorado. She can be reached at caitlin@wateredco.org.

This article first appeared in the Summer of 2020 issue of Headwaters Magazine.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Its editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org.