Voluntary agreement discussions continue despite court fights, state-federal conflicts and skepticism among some water users and environmental groups

Editor’s note: Since original publication of this story on April 17, 2020, voluntary agreements have fallen apart.

By Gary Pitzer

Voluntary agreements in California have been touted as an innovative and flexible way to improve environmental conditions in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and the rivers that feed it. The goal is to provide river flows and habitat for fish while still allowing enough water to be diverted for farms and cities in a way that satisfies state regulators.

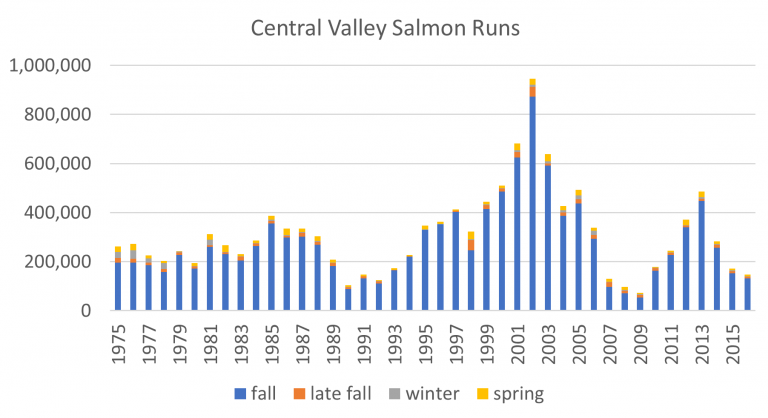

In a state with an array of challenges related to water, this is arguably one of the most pressing in California because of its potential to impact the millions of people who depend on water from the Delta’s key watersheds for drinking and irrigation. The Delta and the rivers that make up its vast watershed are also key habitat for the survival of imperiled chinook salmon runs.

Yet, no one said it would be easy getting interest groups with sometimes sharply different views – and some, such as farmers, with livelihoods heavily dependent on water — to reach consensus on how to address the water quality and habitat needs of the Delta watershed. Adding to the complications is the Delta’s role as the switching yard for water exports serving vast areas of the state as far south as San Diego, more than 500 miles away. Voluntary agreements would require water users to provide new flows for the benefit of rivers and streams throughout the Central Valley and outflow in the Delta, and commit money to fund habitat restoration, science and management to gauge the effort’s impact.

The voluntary agreement effort, initially begun in 2017, got a boost in early February when Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration released a framework for such agreements. That framework outlined a 15-year, $5 billion program that calls for as much as 900,000 acre-feet of new flows and 60,000 acres of new habitat to improve Delta water quality and help reverse the decline of salmon and other native fish in the Delta and its watersheds.

While water agencies throughout the sizeable Sacramento and San Joaquin river watersheds — from Fresno to Redding — embrace the voluntary agreement approach as a means for practicable and reasonable compliance with the state’s Bay-Delta water quality regulations, the idea of voluntary agreements is controversial. They are an alternative to a prescriptive regulatory policy, and that draws concern from some environmentalists and state regulators charged with enforcing water quality in the Delta. But many water users and some nongovernmental organizations view them as a viable compromise that can improve conditions for fish in a more flexible manner.

“We know there are going to be some parties that will oppose this. That’s the nature of California,” said Thad Bettner, general manager of the Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District, the largest irrigation district in the Sacramento Valley covering about 175,000 acres. “This is a lot of hard work – how do you use water for the benefit of the fishery, how do you get projects done, how do you do the science and how do you spend money wisely? Some would rather litigate because that’s their business path, but we believe all these rooms are open for folks to participate.”

Bettner and his cohorts in the vast farmland of the Sacramento Valley were concerned that the second phase of the State Water Resources Control Board’s Bay-Delta Water Quality Plan, now on hold as voluntary agreements are hammered out, would have required a substantial amount of water to stay in the Sacramento River and its tributaries rather than irrigating fields and orchards.

“We know there are going to be some parties that will oppose this. That’s the nature of California.”

~Thad Bettner, general manager of Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District

“To meet that would be devastating,” Bettner said. “I don’t know how we would start to address that type of shortage impact.”

The Bureau of Reclamation, which stores and delivers about 12 million acre-feet through the Central Valley Project, was concerned that requiring percentages of unimpaired flows as the State Water Board sought “would create chaos in California water and result in years of litigation,” Ernest Conant, director of Reclamation’s Mid-Pacific Region, said in a statement.

Instead, he said, voluntary agreements “make the most of scarce water resources and address the landscape-level habitat stressors on species that flow alone cannot overcome.”

Reaching agreement in the midst of litigation

Lawsuits are a chronic fact of life in California water policy, especially in the Delta. There is a multitude of interests, and regulatory actions are often challenged as biased against one or more groups.

The State Water Board adopted (but hasn’t yet implemented) a regulatory plan in 2018 that would require as much as half of the flow to remain in the San Joaquin River system between February and June each year to aid Delta fisheries and combat salinity levels. Although the plan left room for incorporation of a voluntary agreements element, the State Water Board chose not to defer approval of its regulatory plan.

Water users, some of whom had prepared voluntary agreement proposals, promptly sued.

And as the federal government pressed ahead in February with new Endangered Species Act permits used to govern operations of the CVP pumping plant near Tracy, the Newsom administration sued over the adequacy of the environmental requirements. In a statement, California Natural Resources Agency Secretary Wade Crowfoot said the state’s lawsuit against the federal government would not derail voluntary agreement talks.

In a Feb. 24 letter to Gov. Newsom, Interior Secretary David Bernhardt called the suit “ill-founded,” adding that, “over time, I suspect this litigation, like many other California water cases before, will end up with many parties and many twists and turns.”

He added that California and the federal government will face significant administrative and operational challenges related to the intertwined operation of the federally operated Central Valley Project and the State Water Project through the Delta and San Luis Reservoir, with the lawsuit creating “further uncertainty” of water supplies to people, farms and ecosystems.

This is a sticking point for which resolution seems especially challenging: The federal government’s updated CVP operations plan targets more water deliveries to contractors south of the Delta, many of whom use the water to irrigate farmland.

Reclamation said the new CVP operations plan is based on “robust modern science” that enables officials to quickly respond to agricultural, environmental and endangered species conditions.

Meanwhile, California’s Department of Water Resources in late March received what’s known as an incidental take permit for the long-term operations of the State Water Project, creating a separate set of operating rules for its Delta pumping operations. The permit covers four species protected under the California Endangered Species Act: Delta smelt, longfin smelt, winter-run chinook salmon and spring-run chinook salmon.

The permit, which contrasts the federal government’s aim of increased exports, mandates most of the additional outflow that would have been provided in the voluntary agreements, but without their flexibility, adaptive management or habitat provisions, said Paul Helliker, general manager with the San Juan Water District, a federal Central Valley Project contractor on the shores of Folsom Lake, an American River reservoir northeast of Sacramento.

Maurice Hall, associate vice president with Environmental Defense Fund, said the permit “just clouds everything and makes it difficult to see how a voluntary agreement can be landed at this point in time.”

California congressional representatives, led by Sen. Dianne Feinstein, urged Gov. Newsom to work toward coordinated operations of the state and federal pumping facilities.

“This conflict, if allowed to continue, will not only reduce water deliveries just as drought may be returning to California, but also block the successful negotiation of voluntary agreements to meet Delta water quality requirements, which we support,” they wrote April 15.

Despite the difficulties, water users believe the state’s lawsuit against the federal government is not necessarily the death knell for voluntary agreements, although some are worried.

“The voluntary agreements remain the best opportunity to address the flow and non-flow factors affecting our native fish, and we urge the state and federal agencies to remain committed to a negotiated resolution despite the state of California filing suit,” the Modesto and Turlock irrigation districts said in a Feb. 24 joint statement. The statement noted that even though the two districts had sued the state, “that hasn’t prevented us or the state from negotiating in good faith [and] we see no reason why the federal government and the state of California can’t do the same.”

The State Water Contractors echoed that sentiment, saying in a Feb. 21 statement that the differences between the state and federal governments are resolvable. “We encourage the public servants at both the state and federal levels … to get back to the negotiating table and settle these issues,” said Jennifer Pierre, the contractors’ general manager. “The outcome of those successful discussions will be far more effective than anything arising from a lawsuit that may take several years to resolve.”

Others are less sanguine. The litigation has “frozen a lot of people out of what’s even possible going forward,” said Bettner, with the Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District.

Water for people, fish and the environment

Implementing unimpaired flows – essentially keeping more fresh water in rivers – to meet Delta water quality standards requires a separate water rights amendment process to determine who gives up water and how much. The plan would affect communities far and wide, including many urban areas. Michael Carlin, deputy general manager of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, which receives water from the Sierra-fed Tuolumne River, said a comprehensive voluntary agreement plan for the Sacramento and San Joaquín river watersheds requires many individual agreements – an exhaustive process that takes months to sort out.

“Unfortunately, the reality of where we are with voluntary agreements has not matched up with our hopes and our expectations.”

~Rachel Zwillinger, water policy adviser for Defenders of Wildlife

“There are many parties in the room and not all of them are that far along in their agreements,” he said, referring to the process. San Francisco, the Modesto Irrigation District and Turlock Irrigation District emerged from their process successfully to assemble the Tuolumne River Proposal, a voluntary agreement that includes investments of flows, habitat improvements and $80 million in funding commitments. “It’s a really big package,” Carlin said.

Environmentalists and fisheries groups have long decried a paradigm in which they say the Delta’s water quality and ecosystem needs consistently take a backseat to the needs of municipalities and agriculture. The 2009 Delta Reform Act recognized that in calling for reduced reliance on the Delta for water exports and improved regional self-reliance.

The deteriorating environmental conditions that have contributed to the decline and near-extinction of native fish in the Delta are an intractable problem that defies solution. Advocacy groups chafe at the perceived glacial pace of an oft-delayed bureaucratic process (the Bay-Delta Water Quality Plan update is 15 years overdue) in which results are measured incrementally.

Rachel Zwillinger, water policy adviser for Defenders of Wildlife, said her organization supports the concept of voluntary agreements because they offer the promise of faster implementation, habitat restoration and are collaborative in nature.

“Unfortunately, the reality of where we are with voluntary agreements has not matched up with our hopes and our expectations,” she said. “We are in a place where we have not been able to support what the administration has put forward.”

Kim Delfino, former California director for Defenders of Wildlife, said “something has to give,” with either environmentalists relenting or federal water contractors being willing to put more on the table. A voluntary agreement, she said, is supposed to be a part of the State Water Board’s Bay-Delta Water Quality Plan update for which the benchmarks are viable fish populations and a doubling of the salmon population.

There are other complexities as well. The Oakdale Irrigation District and South San Joaquin Irrigation District share rights to the Stanislaus River, which feeds the San Joaquin River. They believe the governor’s framework “appears to be even more onerous” than the State Water Board’s unimpaired flows plan and would be troublesome for fish management.

The problem is well-known: Operating reservoirs to serve the needs of flood protection and instream flow requirements while protecting water rights holders is a delicate balancing act. A certain amount of water has to stay in rivers and tributaries to maintain conditions for fish and to repel salinity in the Delta. Throw the needs of municipalities and farmers on top of that and the finite amount of water gets stretched to the point that tests flexibility.

Describing the basis of the Bay-Delta Water Quality Plan update in 2018, State Water Board staff noted that spring-run and winter-run chinook salmon, longfin smelt, Delta smelt and Sacramento splittail are in distress because of reduced and modified flows, loss of habitat (including access to floodplains), invasive species and water pollution. Flows, they said, “are an essential part of restoring a healthy ecosystem, and flows are the responsibility of the State Water Board.”

But finding a middle ground between the unimpaired flow requirements of the State Water Board’s Bay-Delta water quality update and the alternative of the flow commitments within voluntary agreements is not a fait accompli.

Steve Knell, general manager of Oakdale Irrigation District, believes the voluntary agreements framework as it’s currently conceived would force the draining of the federal New Melones Dam, east of Stockton, as well as the district’s facilities at Donnells, Beardsley and Tulloch to the detriment of the cold water pools in the basin. The framework, he said, “may provide water to the Delta but doesn’t provide the sustainability that instream fisheries and agriculture both need.” In a Feb. 7 letter to state and federal officials, the Oakdale and South San Joaquin irrigation districts urged leaders to carefully account for the water designed to aid rivers and the water aimed at the greater Delta ecosystem, and to also ensure the State Water Project and Central Valley Project, which are junior water rights holders, contribute equitable amounts.

“Many senior water right holders, including the districts, have been willing to offer contributions in the settlement process that benefit their local rivers, and the districts understand that these contributions may also assist the state’s goals for the Delta,” the letter said. “However, these contributions are voluntary, and the needs of the Delta, if any, must be met first by junior water rights holders [such as the SWP and CVP] under California’s rules of water right priority.”

Solving Delta water quality challenges

The State Water Board is required to regularly update its Water Quality Control Plan for the Bay-Delta. The December 2018 approval of the first phase of the plan requires 30 percent to 50 percent of the flows from February through June to remain in the Tuolumne, Stanislaus and Merced rivers. Water supply agencies protested.

“The district believes non-flow measures (such as habitat improvements) have as much or more advantage in helping fisheries in our river than just sending water down,” Knell said.

During the transition between the Gov. Jerry Brown and Gov. Gavin Newsom administrations in late 2018, the outgoing and incoming governors told the State Water Board that voluntary agreements “could result in a faster, less contentious and more durable outcome [and] are preferable to a lengthy administrative process and the inevitable ensuing lawsuits.”

The basis for voluntary agreements began in 2016 when then-Gov. Brown voiced strong support for them and directed the Natural Resources Agency to explore the potential for environmental flows in the Sacramento and San Joaquin river basins. He tapped former Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt as chief mediator for stakeholder talks that began in 2017.

Release of Newsom’s framework is encouraging to stakeholders who spent 2019 building the concept of voluntary agreements.

“This is really the first tangible response that we have seen,” said Helliker with the San Juan Water District. “This is more comprehensive … and builds on previous efforts such as CalFed and the Bay Delta Conservation Plan.”

Andrew Fecko, general manager of the Placer County Water Agency, was the principal representative for the Sacramento region on voluntary agreements. He said the Newsom framework could in some respects mirror, but on a larger scale, previous settlement agreements such as the 2000 American River Water Forum Agreement where Sacramento regional stakeholders committed water and habitat improvements to benefit the lower American River.

“The Water Forum process was in many ways the first of the voluntary agreements, along with the Yuba Accord,” Fecko said, noting the 2008 agreement that committed water from the Yuba River watershed for salmon and steelhead fisheries. “The principal difference with this new statewide effort is that we are expanding the pace and scale of habitat construction on the American River by approximately five-fold, plus offering additional water for the health of the Delta. It’s a tremendous expansion of the regional commitment, but the success we have had with the Water Forum regional effort gives us confidence that we can improve the American River and the Delta.”

Reclamation, which was on board with the 2018 version of a voluntary agreements framework, balked at what the Newsom administration presented in February, saying it was not consulted prior to the document’s release.

“The state has had minimal engagement with us on their proposal, so the rationale for the approach, and the expectations for Reclamation participation, are not clear,” said Conant, the regional Reclamation director.

Crowfoot, California’s Natural Resources secretary, disagreed, saying Reclamation was an active participant in voluntary agreement discussions throughout 2019, including the run-up to releasing the 2020 framework.

“Clearly more work lies ahead to shape the framework into an enforceable agreement to propose to the Water Board,” Crowfoot said. “This includes detailing clear expectations for all parties, including Reclamation.”

“Clearly more work lies ahead to shape the framework into an enforceable agreement to propose to the Water Board.”

~Wade Crowfoot, California’s Natural Resources secretary

Stakeholders resigned themselves to the state’s lawsuit against the federal government. Tom Birmingham, general manager of Westlands Water District in Fresno, the nation’s largest agricultural irrigation district, said discussions on voluntary agreements could proceed, though it would be difficult, and a final agreement could not be reached without Reclamation’s involvement.

California farmers have a lot riding on the successful resolution of the water quality plan. Chris Scheuring, senior legal counsel with the California Farm Bureau Federation, said the decision to pursue unimpaired flows or voluntary agreements is “a tectonic shift either way.”

Voluntary agreements, he said, “hold more promise because they offer the possibility of not doing wholesale damage to the water rights system … as opposed to an unimpaired flows approach, which is a ham-fisted way to go about it.”

Un-ringing the bell

After decades of wrestling with the challenge of finding the right regulatory approach to improve fish survival and water quality, the argument about voluntary agreements represents the latest chapter in a long-running, complicated saga. The state’s legal feud with the Trump administration about CVP operations is an obstacle.

“It’s pretty hard to un-ring the bell at this point,” said Bettner, with the Glenn-Colusa district. “The state and federal governments … could enter into some settlement, but I don’t see that happening anytime soon. We are probably in this cooling off period for a time, then we’ll see where things go after that.”

But there is widespread belief that something is better than nothing regarding improving the Delta ecosystem. Longtime California water scholars Ellen Hanak and Jeff Mount with the Public Policy Institute of California say a negotiated agreement is the way to navigate the thicket of Delta issues.

In a Feb.10 commentary published in CalMatters that called the Newsom administration’s framework “imperfect but necessary,” they noted that current Delta management overemphasizes a handful of endangered fishes and that the voluntary agreements framework “makes an earnest attempt” to go beyond that approach.

“We can appreciate why many parties would want to hold out for a better deal, and absent that, turn to the courts in the hopes of getting their way,” they wrote. “But as seasoned veterans of the Delta know well, the delay-and-litigate strategy has inherent risks because the outcomes are hard to predict.”

Whether through unimpaired flows or voluntary agreements, the way forward is something that “is not going to go unnoticed in history,” said Scheuring, who alluded to the early laws and policies that spurred water development.

“We were encouraged to use the water to make the landscape prosper – to have farms, and to have cities to populate this semi-arid region called the western United States,” he said. “Some people have kind of changed their minds about that human landscape, and hopefully there is a softer way to accommodate that change in thinking through voluntary agreements [and] supply and demand options.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @GaryPitzer

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.

This story originally appeared on Western Water on April 17 , 2020.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism. The Water Desk is seeking additional funding to build and sustain the initiative. Click here to donate.