The American West’s snowpack is valuable for many reasons.

Snowmelt supplies much of the water flowing through the region’s streams, rivers, irrigation canals and household faucets—a vital role that has taken on new urgency this winter as much of the West struggles with scant snow cover.

Snowfall supports countless species, maintains forest health and helps keep a lid on wildfires. It even cools the planet by reflecting sunlight.

Snowflakes also underlie the region’s multi-billion-dollar winter sports industry, fueling local economies and drawing millions of participants. In warmer months, boating and fishing depend on water that was once frozen.

Snow performs all these functions, but can its worth be calculated in dollars and cents? And how is climate change affecting that value?

Like many aspects of nature, snow is easier to monetize in some domains than others. Its ecological benefits are complex, and its aesthetic qualities are subjective: some Westerners love the ice crystals, others dread them.

But in the economic realm, researchers have attempted to put a dollar figure on the region’s snow, and the numbers they’ve generated are huge.

“This stuff’s worth trillions, not billions” of dollars, said snow scientist Matthew Sturm, lead author of a widely cited 2017 paper in Water Resources Research that estimated the value of the water embedded in the West’s snowpack. “I turn on the tap in the Western states—what comes out of it is mostly snow.”

The Colorado River, which supplies drinking water to tens of millions of people and irrigates vast croplands, is primarily driven by snowmelt. The river generated an estimated $1.4 trillion in annual economic activity, according to a 2014 report commissioned by Protect the Flows, a business coalition, and conducted by Arizona State University. Adjusted only for inflation—not the region’s growth—that figure was equivalent to about $1.9 trillion in 2025, underscoring the high stakes of the ongoing, contentious negotiations over how to manage the Colorado River.

For some researchers, assigning a dollar value to snow is more than an academic exercise. In an era of tightening budgets and federal cutbacks in science, economic estimates can help justify investments in monitoring and studying snow—and highlight how much is at risk as the climate warms.

“If you want society to respond, you better talk about things that are fairly immediate, right at people’s doorsteps, and are easy to explain,” said Sturm, a professor of geophysics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute and the author of A Field Guide to Snow.

Or as Sturm’s paper puts it, “the ‘killer argument’ to the wider public that vigorous snow research is important would come by framing the argument in terms of money, something everyone understands.”

Peer-reviewed studies explicitly valuing the snowpack are rare, but some analyses have also calculated the sizable economic impact of snow sports. This winter, skiing and snowboarding in the West have been constrained not only by a lack of snowfall but also by record warmth that limited some resorts’ ability to make artificial snow.

A 2024 report from the National Ski Areas Association concluded that downhill snow sports generate $58.9 billion in annual economic activity in the United States and support an estimated 533,000 ski and snowboard jobs nationwide.

While the snowpack delivers tangible economic benefits—some easier to price than others—snowfall also carries real costs. Any accounting of snow’s economic impact must also reckon with the damage it causes.

Winter weather contributes to fatalities from avalanches in the mountains and from heart attacks in cities among people shoveling snow. But those deaths pale in comparison to the toll on slick roads. Each year, 24% of weather-related vehicle crashes happen on snowy, slushy or icy pavement, and 15% occur when snow or sleet is falling, according to the Federal Highway Administration. More than 1,300 people are killed and more than 116,800 are injured each year in crashes on snowy, slushy or icy pavement, the agency reports, though not all of those incidents are weather related.

Valuing the snowpack’s water

The 2017 paper began with a phone call that Sturm made to Michael Goldstein, a professor of finance at Babson College with whom he had previously collaborated.

“Hey, what do you think snowpack’s worth?” Goldstein recalled Sturm asking.

Goldstein wasn’t a snow expert, but he told Sturm, “If we make some simplifying assumptions here, I could value it for you.”

“I just thought it was a cool question,” said Goldstein, who is also the Donald P. Babson Chair in Applied Investments at Babson.

Since its publication, the study has been cited nearly 400 times, according to Google Scholar.

Viewed through an economic lens, the snowpack’s role as a mountain water tower provided a clear value that Goldstein could quantify.

“Nature naturally stores the water for you for free. You didn’t have to build a reservoir,” Goldstein said. “If that goes away, that actually has a cost. And the cost is the replacement cost of either storing the water or getting water from a different source.”

Climate change is already having a variety of profound effects on the West’s snow, such as shrinking the snowpack season, but the study focuses on one key impact: the shift from snow to rain as temperatures rise.

Even if total precipitation remains unchanged in the decades ahead, a transition from snow to rain—and faster melting of the snowpack—means runoff will occur earlier in the year. In much of the West, however, it may be impossible to capture all that earlier water for later use because dam managers must leave enough empty space in reservoirs to reduce the risk of catastrophic flooding.

“There is not enough reservoir storage capacity over most of the West to handle this shift in maximum runoff and so most of the ‘early water’ will be passed on to the oceans,” according to a 2005 study.

To estimate the declining value of the snowpack in a warming climate, the 2017 paper made some assumptions about the transition from snow to rain—an evolution expected to be more pronounced in warmer regions such as California and Oregon than in colder locations like the Northern Rockies.

Examining a range of future trajectories spanning five to 100 years, the researchers assumed that half of current snowfall would fall as rain by the end of the scenario.

For the 50% of snow that would eventually convert to rain, some of the water could be captured by existing reservoirs. But while Lake Mead and Lake Powell on the Colorado River currently have plenty of room to spare, the authors note that “virtually every report we have found on the heavily dammed water systems of the West suggests that reservoir capacity (except when immediately following drought) is maxed out.” As a result, the paper assumes that water systems would lose two-thirds of the reduced snowmelt runoff.

“We’re losing, essentially, the storage capacity of snow—meaning in lieu of snow, we get rain,” Sturm said.

With their estimates of the amount of water lost as snow shifts to rain, the researchers could then multiply those figures by the cost of water to begin determining the decline in monetary value. The paper uses two water prices to bracket its estimates: $200 and $900 per acre-foot (an acre-foot is the volume of water needed to cover an acre of land to a depth of 12 inches, or 325,851 gallons).

In reality, Goldstein said, the price of water would rise as supplies became scarcer. But the paper holds water prices constant over time, an assumption that yields a conservative estimate of the snowpack’s value.

Discounting the future

The price of water varies greatly across the West, so estimates of the snowpack’s value will necessarily span a broad range. But water costs aren’t the only reason it’s challenging to pin down the snowpack’s monetary worth.

Another challenge the paper grapples with is the changing value of money over time. Even in the absence of inflation, if someone offered you $100 right now versus $100 in a year, the economically rational choice would be to take the $100 today. After all, a lot can happen in a year—and you could invest the $100 in the meantime. But what if the offer were $105 or $110 a year from now?

To convert future benefits into today’s dollars, economists use a “discount rate” that accounts for risk and the preference for receiving payments sooner rather than later. A discount rate is “like the foreign exchange rate between consumption today and consumption tomorrow,” Goldstein said.

The choice of the discount rate can make a big difference in how future costs or benefits are calculated, and it’s often a pivotal factor in studies of the economics of climate change. In the snowpack paper, the authors use three discount rates—1%, 3% and 6%—although they omit the 6% rate in their final valuation “because it is fairly extreme and unlikely to be correct in a water-stressed future world.”

The higher the discount rate, the more heavily future losses are discounted, reducing the economic justification for acting today, such as acquiring new water supplies or building additional reservoirs.

Assumptions about the discount rate, the price of water and future climate trajectories all weigh heavily on estimates of the value of the snowpack’s water. In summary, the authors conclude that about 162 million acre-feet of water is deposited as snow in Western mountains each winter. If half of that snowfall were to fall as rain in the future—and two-thirds of that water were to run off to the ocean without being captured—water systems would lose roughly 53.9 million acre-feet per year. That volume is roughly the combined storage capacity of Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the nation’s two largest reservoirs.

The total replacement cost for the lost water ranged from $120 billion to $4.76 trillion, according to the 2017 study. By comparison, the federal government’s budget totaled about $3.85 trillion in fiscal year 2016.

“To date, a full financial evaluation of the importance of snow in our lives has not been made, but computations here and elsewhere indicate it is on the order of trillions of dollars,” the authors write.

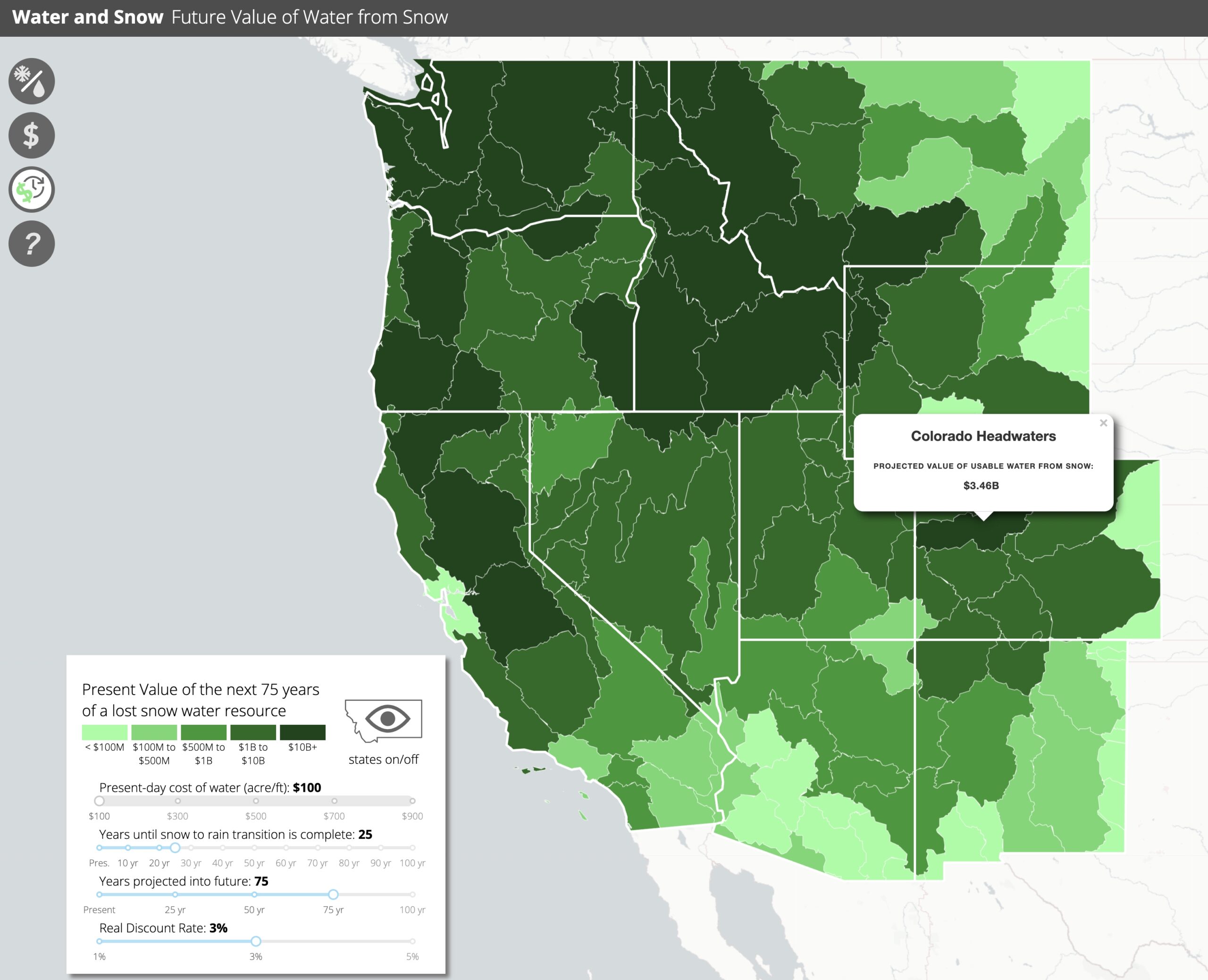

The snowpack’s importance and value vary across the West, with some watersheds more dependent on snowmelt than others. To estimate the local impacts of future snowpack losses, researchers used data from the 2017 study and another paper to create an interactive map that shows the share of water in each Western river basin derived from snow and lets users adjust key variables, including the discount rate, the price of water and the rate at which snow transitions to rain.

Investing in snow science

Jessica Lundquist, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Washington, called the paper “interesting and unique.” Lundquist, who wasn’t an author of the study but is acknowledged for advising the researchers, said the paper not only tried to put a dollar value on the snowpack but “also was trying to put a value on the knowledge.”

“I like the paper because it was a collaboration between a snow scientist and an economist,” Lundquist said. While the estimates of the snowpack’s value are uncertain, Lundquist said the study provides a useful framework for assessing the financial implications of water management strategies.

In a commentary on the 2017 paper, subtitled “Investments in snow pay high-dollar dividends,” Lundquist wrote that the study “puts the value of snow one thousand times higher than the estimates of snow based on tourism alone.”

When the commentary was published, snow scientists were trying to convince NASA to launch a satellite mission to study the snowpack.

“We were often getting questions about what is the value not only of snow, but of studying snow,” Lundquist said.

A satellite dedicated to monitoring snow never launched. But scientists continue to track the snowpack using other spacecraft, along with a suite of tools that includes aircraft, automated stations and manual measurements.

“I think we’re getting progressively better at figuring out how much snow is in the mountains,” Lundquist said. “I think we’ve made tremendous progress in the last 10 years that we can actually quantify it quite well with a number of ways.”

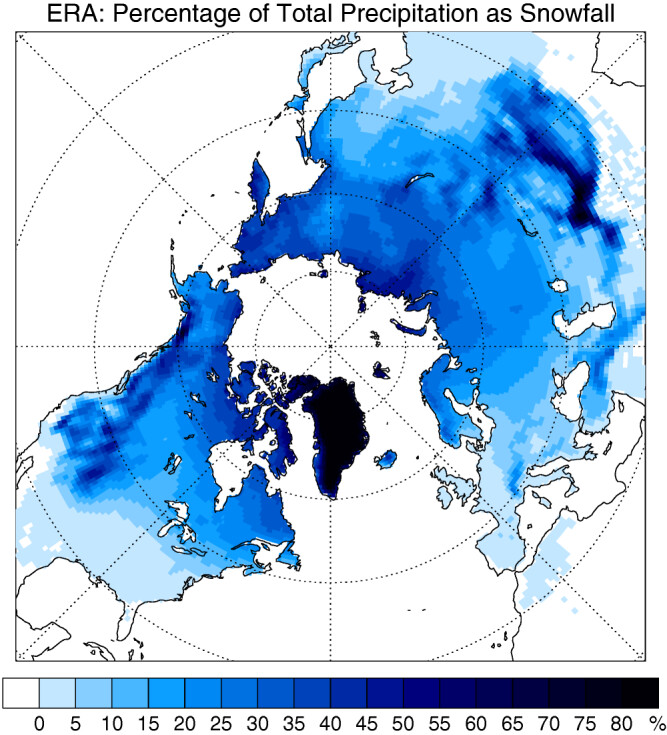

In other parts of the world, however, snowpack monitoring may be very limited. “A lot of what still needs to be done is in other mountain ranges, other places that don’t have these observing networks,” Lundquist said. “There’s a lot of people who depend on water from the Himalaya who just have no idea whether it’s going to be a drought year or a flood year or what is upstream at all.”

Recreational impact of a shrinking snowpack

Beyond supplying water, the West’s snowpack also underpins the region’s winter recreation economy.

During the 2024–25 season, U.S. ski areas recorded 61.5 million skier visits, according to the National Ski Areas Association. This winter, however, visitation across much of the West has suffered amid a widespread snow drought.

In January, Vail Resorts, which is publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange, reported that visits to its mountains so far this season were down 20% compared to last season, primarily because of poor snow conditions. In the Rockies, only about 11% of the company’s terrain opened in December, when snowfall was nearly 60% below the 30-year average.

A number of studies have examined how changes in the snowpack affect ski areas—both historically and in future projections.

Between 1999 and 2010, the U.S. downhill ski industry lost an estimated $1.07 billion in revenue between low- and high-snowfall years, resulting in 13,000 to 27,000 fewer jobs, according to a 2012 analysis by University of New Hampshire researchers. The report was commissioned by Protect Our Winters and the Natural Resources Defense Council, two advocacy groups.

A 2024 study estimated that U.S. ski areas lost more than $5 billion from 2000 to 2019 due to fewer visits and higher snowmaking costs. Compared to the 1960-1979 period, ski seasons from 2000 to 2019 shortened by 5.5 to 7.1 days, according to a model of operations at 226 ski areas.

Looking ahead, the study projected that by the 2050s, ski seasons would shrink by 14 to 33 days under a low greenhouse gas emissions scenario and by 27 to 62 days under a high-emissions pathway. Under those scenarios, annual industry losses ranged from $657 million to $1.35 billion.

The 2024 study accounted for the added expenses of snowmaking, which requires investments in equipment and labor while also increasing water and energy use. It did not, however, include the broader ripple effects of shorter ski seasons on surrounding communities, where hotels, restaurants, bars, retailers, and gas stations depend heavily on tourists’ spending.

A 2017 study examining future climate impacts on skiing and snowmobiling analyzed 247 winter recreation locations across the continental United States and projected how warming would shorten seasons. The authors concluded that “virtually all locations are projected to see reductions in winter recreation season lengths, exceeding 50% by 2050 and 80% in 2090 for some downhill skiing locations.”

Those shorter seasons “could result in millions to tens of millions of foregone recreational visits annually by 2050, with an annual monetized impact of hundreds of millions of dollars,” the researchers wrote. They also noted that limiting greenhouse gas pollution “could both delay and substantially reduce adverse impacts to the winter recreation industry.”

A smaller, less reliable snowpack can also affect summertime recreation by reducing streamflows and reservoir levels that support fishing, boating and other water-based activities.

In Colorado, for example, outdoor recreation accounted for 3.2% of the state’s gross domestic product in 2023, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Boating and fishing generated $689 million in economic activity in the state, while snow-related recreation was valued at $1.56 billion—more than any other state.

Other benefits—and costs—of snow

The snowpack’s importance to winter recreation and the West’s water supply are among the easier values to quantify, but they’re not the only benefits snow provides.

On a global scale, one of the most valuable functions of frozen water is that it reflects far more sunlight than bare ground or open ocean. This reflectivity—a property known to scientists as albedo—helps cool the planet.

A 2013 study examining the thawing Arctic attempted to monetize the loss of that cooling effect. The decline in Arctic snow and ice—along with increased methane emissions from melting permafrost—was estimated to cost society $7.5 trillion to $91.3 trillion from 2010 to 2100. “The frozen Arctic provides immense services to all nations by cooling the earth’s temperature—the cryosphere is an air conditioner for the planet,” the scientists wrote.

Then again, the loss of snow could reduce some costs to society.

“There’s some side benefits,” Goldstein said. “You might not have a flood because you’re not going to have a massive runoff all at the same time. That does happen. Some things will be reduced.”

If snow disappeared, so too would snow days that disrupt travel and hamper economic productivity. Winter road maintenance accounts for roughly 20% of state transportation department maintenance budgets, according to the Federal Highway Administration, which estimates that state and local agencies spend more than $2.3 billion annually on snow and ice control annually.

Between 1980 and 2024, the United States experienced 24 winter storms that each caused more than $1 billion in damages, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information. Collectively, those disasters cost $104.2 billion and claimed 1,453 lives.

While vehicle crashes, skier visits and acre-feet of snowmelt can be quantified and priced, snow’s benefits and costs also encompass many things that are difficult—if not impossible—to calculate.

In many ecosystems, for example, snow and snowmelt are vital for plants and animals that have their own economic value, not to mention their intrinsic worth. The 2017 snowpack study did not attempt to price these so-called ecosystem services, which include keeping forests healthy, maintaining cold-water fisheries and sustaining biological diversity.

Even more challenging to value are the mix of emotions that snow evokes. Beauty—and misery—are in the eye of the beholder.

“Some people want their white Christmas,” Lundquist said, “and others are like, please don’t shut down my city.”

This story was produced by The Water Desk, an independent journalism program at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism.