This story was originally published by Aspen Journalism on January 9, 2026.

A new study pinpoints the main cause of harmful algal blooms in Blue Mesa Reservoir, and includes a recommendation for a minimum water level to prevent them.

A study released in December by scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Park Service said the main driver for recent toxic harmful algal blooms in Blue Mesa is low reservoir levels, which create shallow and warm conditions favorable for algal growth. The study also says maintaining a water-level elevation above 7,470 feet might help minimize the occurrence of these blooms.

“When the reservoir gets below 7,470, which is 49 feet below full pool, every year that that happened during the growing season, the algae thrived and ended up producing toxins greater than health advisory,” said Katie Walton-Day, a research hydrologist with the USGS and a lead author on the study. “So the message is that that level is important, and I think more work needs to be done to understand the timing of that level.”

Blue-green algae that resembles pea soup or spilled paint on the water’s surface can form when nutrients are present and water temperatures are between 68 and 77 degrees Fahrenheit. These cyanobacteria blooms can be toxic to humans and animals, leading the park service to post warning signs to keep kids and pets out of the water in certain areas of Blue Mesa. These outbreaks can pose a threat to public health and negatively impact the local outdoor recreation economy.

According to Walton-Day, beginning in 2018, toxic algae in the reservoir exceeded standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment for recreational water quality and swimming, triggering the need for more research. Harmful algal blooms occurred again in 2021 and 2022. Scientists from USGS and the park service used remote sensing to detect the blooms and collected water quality data from 2021 to 2023 as part of the study.

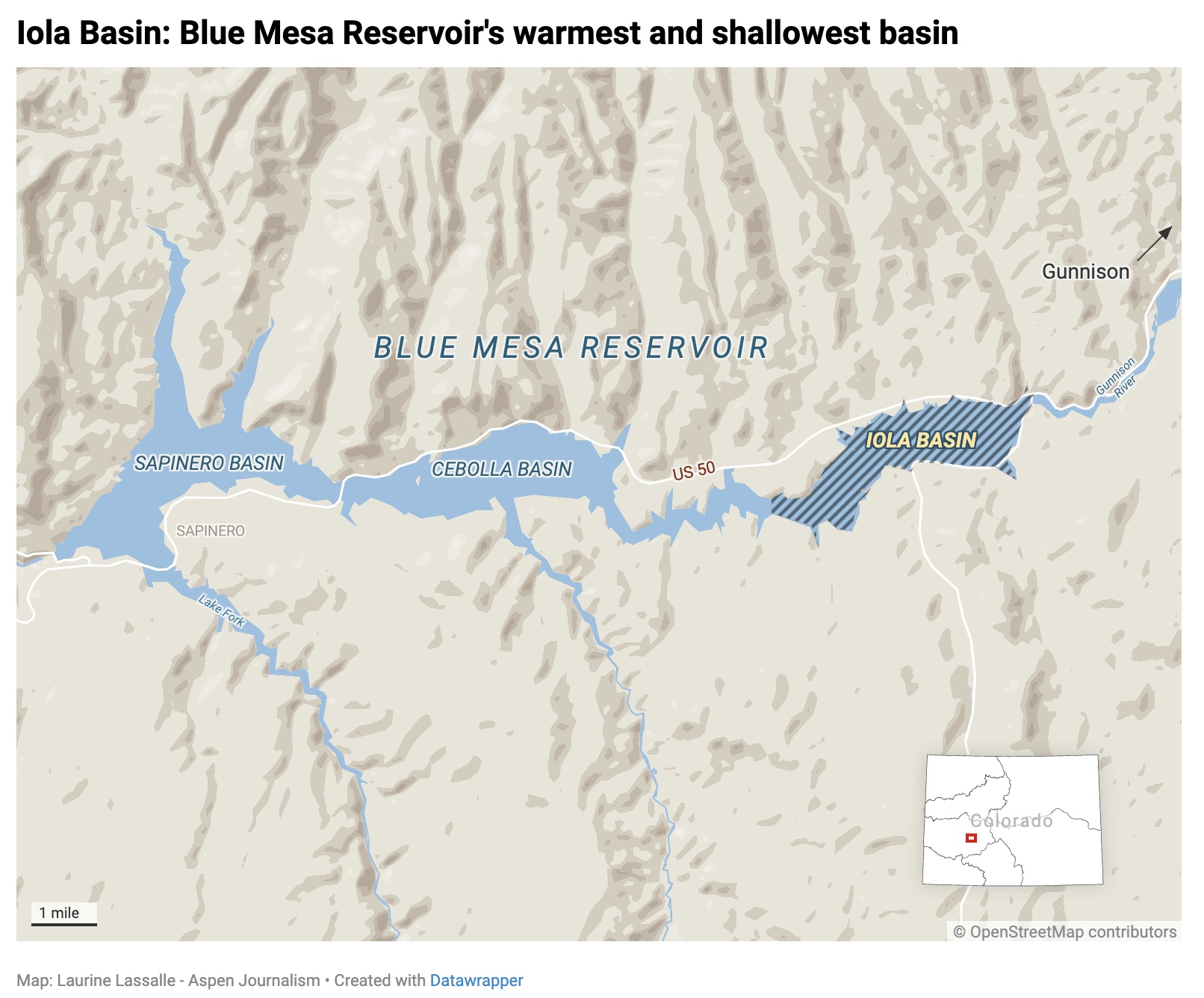

Formed by damming the Gunnison River, Blue Mesa Reservoir is Colorado’s largest reservoir, with a capacity of about 940,000 acre-feet. Three separate basins make up the reservoir: Sapinero, Cebolla and Iola. Iola is the farthest upstream, the warmest and shallowest — and also the most likely to have toxic algal blooms.

“Iola develops these broad, shallow areas where things are warm and stagnant,” Walton-Day said. “We think that also contributes to the formation of algae.”

As near-daily afternoon winds kick up, they can stir up algae from the sediment on the bottom of the reservoir, further fueling the issue. The study also found no evidence that nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen were increasing, leaving low water levels as the likeliest main culprit of the blooms in recent years.

More reservoir releases?

The Upper Gunnison Water Conservancy District helped fund the study by contributing $93,000 cash and in-kind donations, according to General Manager Sonja Chavez. Other sources of funding, in addition to the USGS and the park service, include the Colorado River Water Conservation District, Project 7 Water Authority, Gunnison County and Uncompahgre Valley Water Users Association.

In 2021, Blue Mesa’s marinas were forced to close early for the season because of low water levels caused by emergency releases from three reservoirs in the Upper Colorado River Basin: Blue Mesa, Navajo and Flaming Gorge. Water managers from Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming were not happy with this unilateral action by the feds.

“They made those releases at a really horrible time here when water levels were low,” Chavez said. “You have to think about the economic impact to this community associated with those releases.”

But the study points to another reason for concern: The 36,000 acre-feet released from Blue Mesa contributed to a large reservoir dip, when water levels fell well below the crucial threshold for harmful algal blooms cited in the report of 7,470 feet.

“They promised us they won’t [take unilateral action] again, but there’s nothing that binds them to that verbal promise and now we have a new administration,” said John McClow, attorney for the conservancy district and an alternate representative to the Upper Colorado River Commission. “Reclamation is definitely looking at those Upper Initial Units as a resource to sustain Lake Powell.”

As water managers attempt to balance the need for water to boost Lake Powell, they now have another upstream impact to take into consideration. This year’s low snowpack and dismal projections mean there could be more releases from Blue Mesa in the future and, therefore, increased potential for more harmful algal blooms. In December, officials from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation said releases from the three reservoirs — known as the Colorado River Storage Project Act reservoirs or the Upper Initial Units — are one of the tools the federal agency could use to prop up levels at Lake Powell to protect the ability to make hydropower at Glen Canyon Dam.

There’s a lot of uncertainty about how the Colorado River will be managed, reservoirs operated and shortages shared after 2026. Water managers from the seven states that share the river haven’t been able to find consensus about how to manage the river after the current guidelines expire at the end of the year.

And it’s unclear how much water the Bureau of Reclamation plans to release from each of the three upstream reservoirs or when. In a prepared statement, a spokesperson from the bureau said it is too early in the winter season to determine if additional upstream water releases will be needed and how much water those reservoirs will have available to release.

The bureau spokesperson said the agency does consider water quality and the prevention of toxic algal blooms when making decisions regarding reservoir releases, but that they must also “take into account the agency’s primary obligations, which include meeting downstream water deliveries for local irrigation districts with senior water rights to support agricultural needs, and fulfilling requirements related to endangered species protection.”

Colorado River expert and author Eric Kuhn said that if reservoir releases happen in 2026, most of the water will come from Flaming Gorge.

“Unless things get really stormy in the next two months, we’re going to need a big DROA release,” Kuhn said, referring to the Drought Response Operations Agreement, which lays out actions each year to protect levels at Lake Powell. “Almost all of the water is going to come from Flaming Gorge. Simply, it’s a water-availability issue.”

With a capacity of nearly 3.8 million acre-feet, the reservoir that impounds the Green River on the Utah-Wyoming border stores much more water than either Blue Mesa or Navajo reservoirs.

Still, the prospect of more low water years in the future worries Chavez, whose specialty is limnology, or the study of freshwater lakes.

“Once you get these harmful algal blooms forming, all those algae die every year, they go back down to the bottom, and if you get the lake turnover, all that stuff gets remobilized throughout the system and you’re just causing a problem that’s self-feeding,” she said. “The more these reservoirs get tapped, the bigger this problem is going to become.”