Sometimes snow falls when the air temperature is warmer than water’s freezing point of 32° Fahrenheit.

Figuring out the dividing line between rain and snow has long flummoxed forecasters, especially in places like the high country of the American West, where complex topography and dramatic elevation differences shape the weather.

The fuzziness of the boundary can have life-or-death implications.

If rain falls on top of snow, that can cause disastrous flooding.

“We saw that in Yellowstone in 2022,” said Meghan Collins, associate research scientist at the nonprofit Desert Research Institute. “There was a really large snowpack in the Northern Rockies, forecasters called for snow, and it came as rain and it washed out roads, it washed out bridges and it washed out houses.”

Meteorologists and transportation officials want to know if roads are being coated with rain or snow so they can alert the public and deploy snowplows.

Avalanche experts care about the type of precipitation because that can be a pivotal factor in predicting the risks facing people recreating in the backcountry.

As climate change shifts snowflakes to raindrops, a better understanding of the dividing line between rain and snow is also of interest to water managers, ecologists and others who monitor streams and rivers that support both ecosystems and economies.

To gain a clearer picture of the rain-snow transition and its impact on the water cycle, scientists have been using a free phone app and data from thousands of volunteer observers who provide real-time reports of what precipitation type they’re seeing.

The observations from the NASA-funded citizen science project—known as Mountain Rain or Snow—have highlighted the shortcomings of existing approaches to differentiating the phases of precipitation, according to a study published in Geophysical Research Letters in December.

“It’s very hard for weather monitoring technologies to estimate rain versus snow without ground-based observations, and so this project is seeking to fill a gap that has connections to multiple fields,” said Collins, a co-author of the study who works on the crowdsourcing project.

So why might it be snowing when the temperature is several degrees above 32?

“This is not a change to the law of physics, but it does point to the complexity of our atmosphere,” Collins said. “Snow forms in layers of the atmosphere that are colder than where we live, work, and play.”

On the way to the ground, the snowflakes may persist while passing through warmer layers. Humidity levels play a key role in determining the rain-snow threshold. In relatively dry, continental conditions, such as in the Rocky Mountains, there are fewer water vapor molecules in the atmosphere, so the melting of snowflakes is slower, preserving them longer.

Crowdsourcing precipitation data

The project, which began in the Sierra Nevada in January 2020, relies on nearly 2,000 observers who have submitted more than 85,000 observations of precipitation as of December 2024 (see bottom of post for how to sign up).

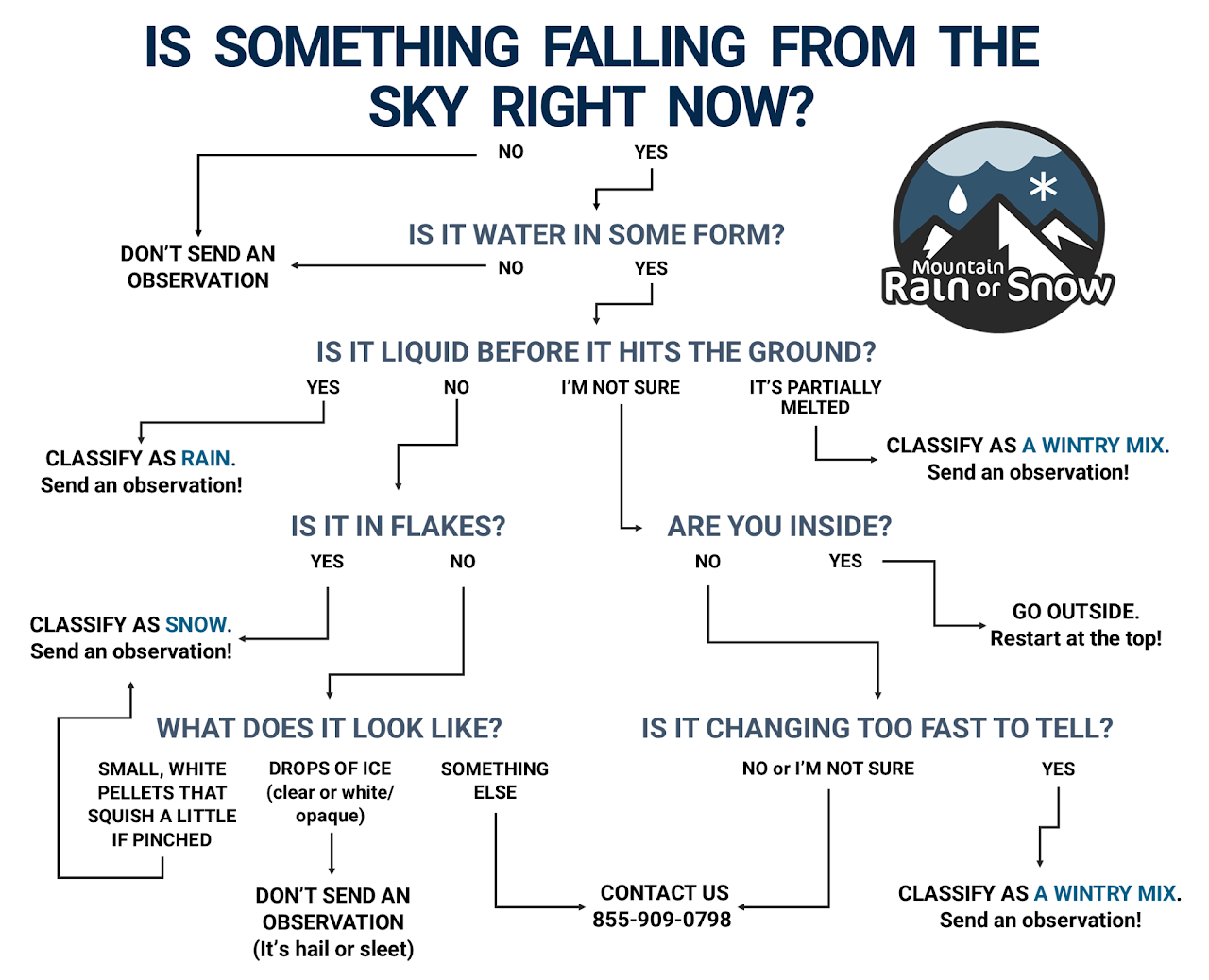

Volunteers are asked to use an app to record whether they’re seeing snow, rain or mixed precipitation. The app records the time and location, using the device’s Global Positioning System, then transmits the data for processing.

There’s no need for observers to record the temperature. That information comes from the nation’s extensive network of weather sensors, plus some complex modeling that fills in the intervening areas with temperature data.

“We ask observers to send us observations whenever they see precipitation start or change type,” Collins said. “It’s those transitions between rain, snow and that wintry mix that we’re really interested in, especially around the freezing point.”

NASA’s interest in the project stems from its Global Precipitation Measurement Mission, a constellation of satellites that tracks weather via remote sensing and uses algorithms to determine if it’s raining or snowing.

The project helps NASA understand “where the satellite mission does well in estimating precipitation phase and where it struggles,” Collins said.

The December research paper used 39,680 observations from volunteers from January 2020 to July 2023 to assess three forecast products that distinguish between rain and snow.

“All products performed poorly in detecting subfreezing rainfall and snowfall above 2°C,” according to the study. “Crowdsourced data could help enhance methods used to determine precipitation phases and improve real-time weather forecasts.”

The study noted that previous research has revealed difficulties in determining what type of precipitation is falling from about 0°C to 4° Celsius (32° to 39.2° Fahrenheit).

“Unlike commonly used methods for determining precipitation phases, crowdsourcing visual observations of precipitation phases provides an effective and accurate way to monitor rain and snow patterns,” the paper concluded.

Informing forecasts

Raindrops and snowflakes are both made of water, but whether one or the other falls makes a big difference to water managers. A snowflake might remain up in the snowpack for months, while a raindrop might quickly run toward a river. A better understanding of the rain-snow threshold can inform the accounting of water planning efforts that hinge on the annual runoff season.

“If we know that there’s going to be more snow coming down, then we know better how much water we have in our snowpack, which is good for water balances and water budgets for the next water year,” said Nayoung Hur, another co-author of the study and a water resources engineer at Lynker, a science, engineering, and technology company. “How much streamflow are we going to have? What’s the peak runoff going to be? Are we going to have enough groundwater recharge for areas that rely on groundwater for their drinking water source or just water source?”

Another potential benefit of the project is informing avalanche forecasts.

“To the extent that what they’re doing improves the weather forecast, it’s massively helpful to us,” said David Reichel, executive director of the Sierra Avalanche Center, which provides forecasts for the greater Lake Tahoe area. “Precipitation is a major driver of avalanches, and so understanding if you’re going to get a foot of snow or an inch of rain or six inches of snow and then a half inch of rain—this part of the weather forecast is really influential on the avalanche forecast and what avalanche problems we’re likely to expect.”

One challenge is that the avalanche center publishes its forecasts early in the morning, but very few people are submitting real-time observations in the wee hours when it’s still dark out.

Rain-on-snow events can increase the avalanche danger by adding weight and infiltrating into the snowpack.

“Water in the form of rain is heavy, and even a little bit on a winter snowpack will significantly increase the avalanche danger,” Reichel said.

The Mountain Rain or Snow project is helpful to a variety of users, but it confronts a number of obstacles due to the complexity of mountain weather. For example, while computer models can provide high-resolution estimates of the temperatures where observations are recorded, those figures are not without errors since there are only so many weather stations out there.

Another challenge, Hur said, is that “a lot of people end up submitting their observations where it’s most comfortable,” such as from home, so there’s a comparative lack of data from places like the backcountry and mountaintops.

Even so, the extensive network of observers provides useful data and the scientists involved in the project say they’re impressed by the volunteers’ dedication. When the project ran a photo contest, it received 177 submissions from the field.

“Our observers are amazing,” Collins said. “There’s just a lot of talent and motivation in the community.”

How to participate in the Mountain Rain or Snow project

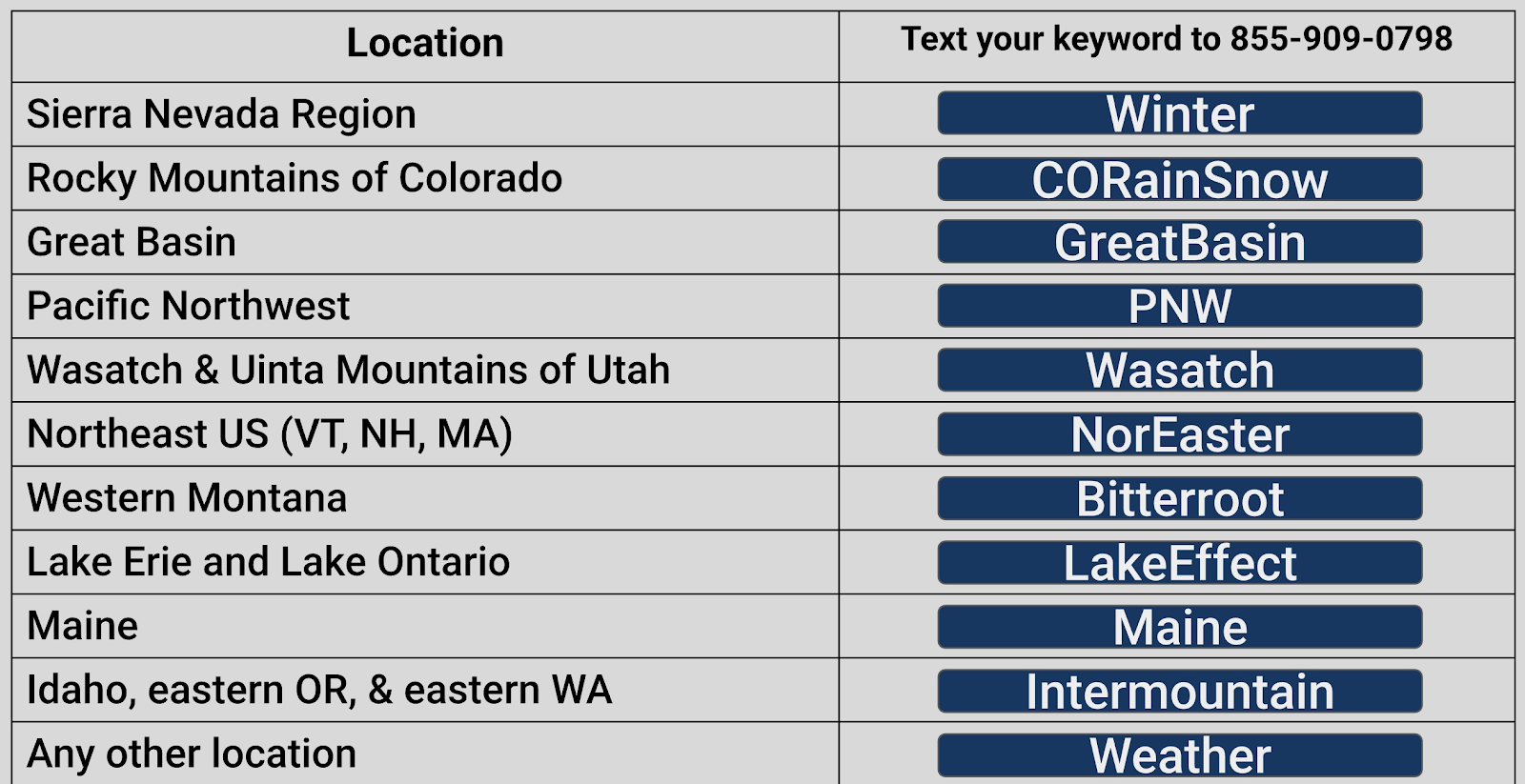

- Sign up to receive storm alerts via text: using the table below, find your region’s keyword and text it to 855-909-0798. You’ll receive a link to the web-based app.

- Visit this page to sign up for the program.

- Send observations through the app whenever you see rain, snow or mixed precipitation.

- The app needs to know your location to submit an observation, so ensure your device’s location permissions are on.

- You can record observations even if you don’t have cell or internet service. The app allows you to submit the data at a later time.

- Questions? Text 855-909-0798.