By Jerd Smith

Colorado River Basin states will succeed in complying with an emergency federal order that came just last week to slash water use by millions of acre-feet, experts said, but it will take time plus major deals with farm interests and tribal communities, and will likely require that the basin, whose flows and operational structure were divided by the 1922 Colorado River Compact, be united and managed as one entity.

“The world has shifted under our feet this week,” said Doug Kenney, former director of the Western Water Policy Program at the University of Colorado Boulder. “We are all being asked to innovate at a pace and scale that I don’t think we were thinking of. Sometimes a big threat from the federal government is what you need.”

The states have 60 days to come up with a water reduction plan.

Kenney’s comments came June 17 at the Getches-Wilkinson Law Conference on Natural Resources at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Kenney was referring to a June 14 emergency request from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton, telling the seven states that comprise the Colorado River Basin that they will need to find 2 million to 4 million acre-feet of water use reductions in the next 18 months to stave off a potential collapse in the Colorado River system.

Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, in comparison, use roughly 3.5 million acre-feet (maf) annually.

Lake Powell, which can store roughly 26 maf of water when full, and its sister reservoir, Lake Mead, with 29.4 maf of storage, are two of the largest reservoirs in the United States.

A 20-year megadrought, considered to be the worst in 1,200 years, including two back-to-back intense drought periods during 2020 and 2021, has left each of the reservoirs well below their former levels, with Lake Mead just 24% full, and Lake Powell down to about 27% of capacity.

Touton’s order came just six weeks after the federal government and the states approved two other major agreements, one to hold 500,000 acre-feet of water in Lake Powell that would normally have been released to Lake Mead for Arizona, California and Nevada, and another releasing 500,000 acre-feet from Flaming Gorge Reservoir on the Utah-Wyoming state line to further boost levels in Lake Powell.

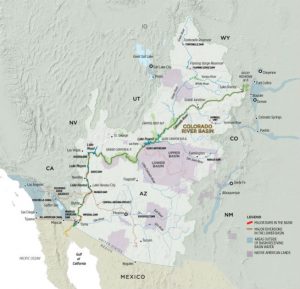

Under the terms of the 1922 Colorado River Compact, the Upper Basin is made up of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, while the Lower Basin comprises Arizona, California and Nevada and Mexico.

Each basin was given the rights to 7.5 million acre-feet of water, with an additional 1.5 million acre-feet of water for Mexico. But the river has generated much less than that for decades, and since the megadrought began in the early 2000s, the river’s flows have declined and stored water supplies in Powell and Mead have shrunk as well.

How the new reduction orders will affect supplies in Colorado and other Upper Basin states, who have never used their full entitlements to the river’s flows, isn’t clear yet.

To find ways to cut 2 million to 4 million acre-feet of water will require intense negotiations, and maybe even legal action, according to Bill Hasencamp, who manages Colorado River supplies for the Los Angeles-based Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which serves 19 million people in Los Angeles, San Diego and elsewhere.

Under the terms of the 1922 compact and subsequent agreements, California was entitled to use 4.4 million acre-feet of Colorado River Water, but because supplies were abundant and the river generated millions of acre-feet of extra water every year, California routinely used more than its share. That changed in 2003, when the federal government ordered it to cut back.

With last week’s announcement, Hasencamp said, “It feels like I am going through 2003 again. The lessons are still applicable today. Having a federal threat is a pretty good motivator.”

Despite the enormity of the challenge, Hasencamp said he was optimistic that the states would reach a deal, just as they did 20 years ago.

“It’s going to be painful,” Hasencamp said. “Some people will lose their jobs. These are such tough decisions that there could be fallout…but we have some pretty smart people in the basin. Let them be creative.”

Twenty years ago, California was able to reduce its use by arranging intermittent land fallowing deals with major agricultural irrigators, such as the Imperial Irrigation District. It also made deals with Arizona and Utah to stabilize its water supplies.

Now, Hasencamp said, California is down to using just 4.2 million acre-feet of Colorado River water annually, below its formal allocation.

Some 30 tribes in the seven-state basin control millions of acre-feet of water, or an estimated 22% to 26% of the basin’s annual water supplies, some of which has never been diverted or stored due to a lack funding, pipelines and reservoirs.

Tribal concerns will have to be addressed to reach a deal, said Lorelei Cloud, a council member with the Southern Ute Tribe in southwestern Colorado.

Even now, she said, “Tribes are not compensated for their water that is in Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Everybody is depending on tribes not to use their water. But the federal government needs to fulfill its trust responsibilities to the tribes.”

James Eklund, a water attorney and former director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, said that the federal government and the states will have to relax or eliminate the divisions between the upper and lower basins, because they sharply limit flexibility in managing the drought-strapped river system.

“We are in a crisis and we have an opportunity to reexamine [the 1922 compact]. Even five years ago, I would have said that is too much. That’s going too far.

“But a whole-basin approach is much more appropriate than continuing this fiction of an artificially bifurcated basin,” Eklund said.

Colorado officials have said repeatedly that they have always had to live with cutbacks as a result of lower flows that naturally occur in the system when you’re up high in the headwaters and don’t have substantial water storage to fall back on.

They also point to the two emergency releases from Flaming Gorge in 2021 and 2022, and releases from Colorado’s federally owned Blue Mesa Reservoir, as evidence of their having already given plenty of water to help stabilize the system.

And though Lower Basin states have already begun implementing cutbacks involving hundreds of thousands of acre-feet of water, this new ask is much larger and must be answered quickly, experts said.

Because farm interests control roughly 80% of the river’s water supplies, farmers are going to be asked to fallow land and to put a price on how much that will cost other water users and federal government.

Peter Nichols is a Colorado water attorney who helped craft a large-scale farm fallowing program in the Lower Arkansas Valley that was modeled after work that California’s Metropolitan District did in the early 2000s. Rather than buying farm land and drying it up, what’s known as the Super Ditch project allows farmers to lease their water when it is convenient and in times of drought.

The Super Ditch took years in water court and three trips to the Colorado legislature to finally implement, but it serves as an example of what can be done through the seven-state basin to achieve the federally mandated cutbacks, Nichols said.

“Irrigators are going to be willing to do this,” Nichols said. “But they’re going to be interested in three things: price, price and price.”

“They are also interested in flexibility,” Nichols said. “They don’t want to be tied in forever. If the price of onions goes through the roof, they will want out. They will want to be able to grow onions.”

Still the framework is out there and is workable, he said.

“[California’s] Metropolitan proved you can do this. But you can’t do it quickly. Reclamation has drawn a couple of lines in the sand and it has changed what we have to do and the amount of time we have to do it in,” he said.

Correction: An earlier version of this article failed to note that the four Upper Basin states combined use roughly 3.5 million acre feet of water annually.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.