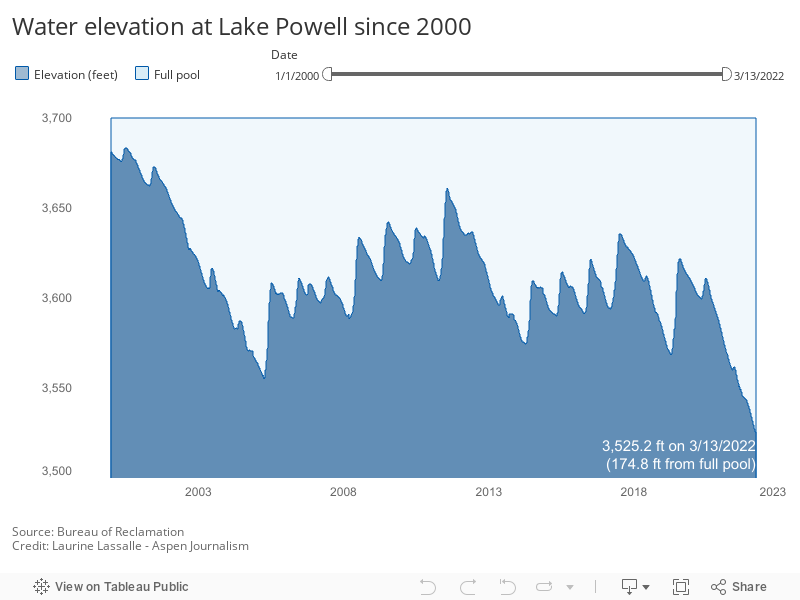

Despite emergency releases from three upper basin reservoirs last summer and fall aimed at propping up Lake Powell, levels in the reservoir are projected to dip below a critical threshold in the coming days.

The second largest reservoir on the Colorado River is predicted to fall below the target elevation of 3,525 feet between March 11 and 15, according to Becki Bryant, public affairs officer with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The dip is temporary and levels are expected to rise above the threshold again in May when snowpack runoff gets underway. As of March 10, Lake Powell was at 3,525.66 feet.

The 3,525 feet number is important because that was the elevation set in the 2019 Drought Response Operations Agreement (DROA). That number gives water managers a 35-foot buffer in which to take action before water levels reach the minimum level needed to generate hydropower for millions of people in the southwest: 3,490 feet.

“All of us sort of picked 3,525 as a cushion to give us some maneuvering room in case the negotiations took time or the forecasts were off,” said Eric Kuhn, author and former general manager of the Glenwood Springs-based Colorado River Water Conservation District and one of the crafters of the Drought Contingency Plan. “If you’re going to preserve power pool a year from now, you need a number of months to get that job done.”

Last summer and fall the Bureau of Reclamation released 161,000 acre-feet from the upper basin reservoirs to prop up Powell, including 36,000 acre-feet from Blue Mesa Reservoir in Gunnison County, 125,000 acre-feet from Flaming Gorge and 20,000 acre-feet from Navajo Reservoir. The releases were expected to boost Powell by about 3 feet.

Some Colorado water managers criticized the move for what they said was a lack of advanced notice, which cut short the summer recreation season on Blue Mesa. Some also questioned the timing of the releases. Hot, dry weather in late summer and fall means more transit losses because plants and soils will pick up more of the additional water, with fewer acre-feet making it all the way to Lake Powell.

“I think that is a valid criticism,” said Dave Kanzer, an engineer with the River District. “We have concerns about the timing of the release.”

According to Bryant, without the releases — plus a second DROA action of holding back 350,000 acre-feet in Powell to be released later this spring — Powell levels would be 8.5 to 9 feet lower than they are now.

“Those two actions combined have prevented the drop in elevation from being deeper and longer in duration,” she said.

But the releases came at the cost of depleting Blue Mesa, which on March 9 sat at 29% full, down from 48.5% on March 9, 2021. As this angered some in Colorado, and the amount of water is proving to be the proverbial drop in the bucket, questions of the impact of the releases and were they worth it generate debate.

“That’s a difficult question,” said Rebecca Mitchell, director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board. “You have to look at the past few years and what the future will hold for us. So that’s going to be a difficult question.”

Director of the Upper Colorado River Commission Chuck Cullom said criticism of the reservoir releases is fair, but that in the end, they did what they were intended to do: Prop up Powell to give water managers time to hammer out an annual operating plan.

“I think the data supports that the 2021 actions, although imperfect, were beneficial to prop Lake Powell up,” he said.

New framework coming for emergency releases

Representatives from the upper basin states — Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico — along with Bureau of Reclamation officials are working on an annual framework for sending water to Powell that would avoid a repeat of 2021’s emergency releases.

“As early as May we will have completed the DROA plan for May through April of 2023 releases with the same intent: to keep Lake Powell above 3,525 if we can, but certainly to keep it above power pool of 3,490,” Cullom said.

Mitchell said water managers coming together to figure out a path forward with annual drought operations, which came about as a result of the federal government stepping in with last year’s emergency releases, is valuable.

“That includes a full analysis of potential options and implications of the various options, so we have an opportunity now to fully consider timing impacts and any other matters,” Mitchell said. “I think that’s going to be helpful.”

DROA public comments

Glen Canyon Dam is what’s known as a “cash register” dam. The power it produces is used to repay the cost of building the project and provide power to millions of people in the southwest, including Colorado. Lake Powell is also a strategic bucket for the states of the upper basin — Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — which allows them to meet their water delivery obligations to the lower basin under the Colorado River Compact. Water managers have many good reasons for wanting to preserve this system.

But during the public comment period for the DROA plan framework, which closed on Feb. 17, some questioned the wisdom of trying to preserve Powell at all, especially in the face of the worsening impacts of climate change. William Lipscomb, a climate scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, said the DROA draft does not adequately address the long-term challenges posed by climate change. As hotter temperatures and drought continue to rob the river of flows, lakes Powell and Mead are at less than one-third full, their lowest levels since filling.

“Given that Lake Powell is approaching dead pool, I hope you will consider the eventual phasing out of Lake Powell as a reservoir,” he wrote in a comment letter. “Storage could be consolidated in Lake Mead, opening more of Glen Canyon for restoration.”

Sixty-one comments, 55 of them form letters, shared this sentiment, urging federal officials to consolidate storage in Lake Mead or remove Lake Powell.

But the vast majority of comments — 698 — came from people asking Reclamation officials to fill Lake Powell. Nearly all of these were form letters and said the target elevation of 3,525 is too low for recreation. Some recounted fond family boating experiences on the human-made lake. The low water levels have led to the closure of marinas and boat ramps in recent months.

“While maintaining Lake Powell at higher elevation levels will require tradeoffs elsewhere in the Colorado Basin, Lake Powell should be given preferential treatment,” read one form letter from Hannah Cook. “It is a national treasure for outdoor recreation, vitally important for local economies, the reservoir and dam provide clean energy and water certainty for downstream users.”

A single comment from a southern Utah resident and boatman on the Green and Colorado rivers named Phoebe Brown argued that decision makers should value the long-term ecological implications over economic needs or power generation.

“Thinking about my life and my future, the only hope I see in the West is maintaining the ecological integrity of river corridors, and I want to see Lake Powell managed for sedimentation and making sure there is healthy water and a livable future for young Westerners like myself,” she wrote.

Aspen Journalism covers water and rivers in collaboration with The Aspen Times. This story ran in the March 11 edition of the Craig Press, Steamboat Pilot & Today, March 12 edition of The Aspen Times, the March 14 edition of the Vail Daily.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.