After a lengthy water court battle, the city of Glenwood Springs has secured a conditional water right for three potential whitewater parks on the Colorado River.

The new recreational in-channel diversion, or RICD, water right is a win for Colorado’s river recreation community, even though the city had to make concessions to future water development to get it.

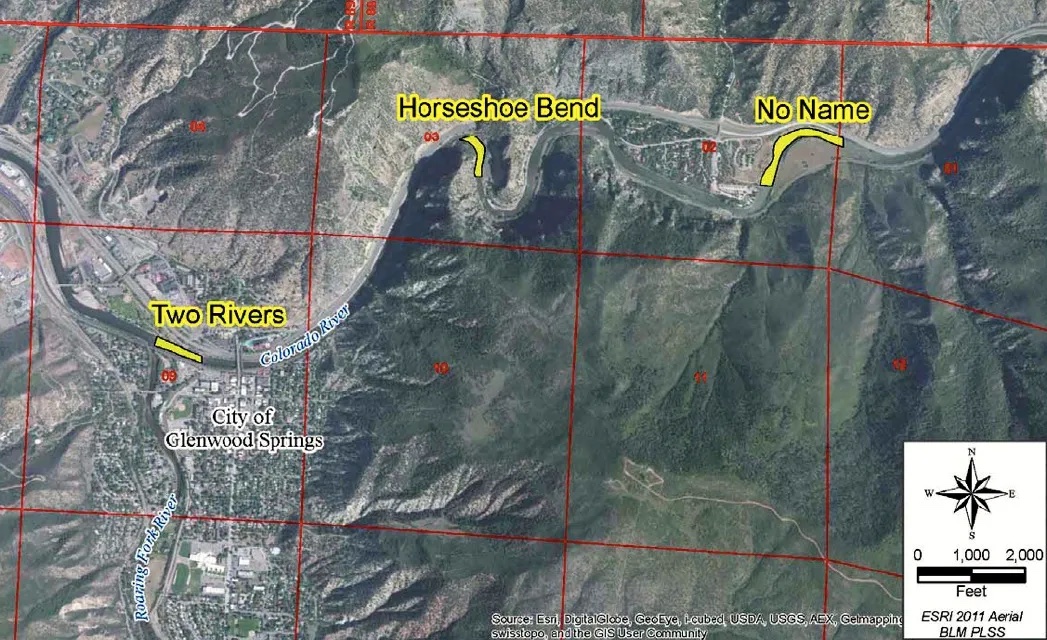

The new water right is tied to three proposed boating parks: No Name, Horseshoe Bend and Two Rivers. The City plans to build a park at just one of the sites. The whitewater parks would be able to call for higher flows during certain times of year — 1,250 cubic feet per second from April 1 to Sept. 30; 2,500 cfs between June 8 and July 23 and 4,000 cfs for five days between June 30 and July 6.

The different flow rates would allow beginner, intermediate and expert boaters to all enjoy the boating structures, which have yet to be built. The five days of high flow would allow Glenwood to host a competitive event around the Fourth of July holiday.

The decree granted by water court judge James Berkley Boyd on March 23 is the culmination of nine years of work for Glenwood Springs, crafting agreements or otherwise settling with all parties that had filed statements of opposition in the case.

“We know outdoor recreation is a big part of our local culture and local economy so being able to have this opportunity to expand options and enhance options for our river recreation is really exciting,” said Bryana Starbuck, public information officer for the city of Glenwood Springs.

The city will now begin looking at designs for each of the three sites, investigating potential funding options and choosing the one that is the best fit, Starbuck said. The city will have to reapply to water court in six years to show it’s making progress on the parks to maintain the conditional right.

Glenwood Springs joins a handful of other Colorado communities with RICDs for human-made whitewater features, including Steamboat Springs, Pueblo, Fort Collins, Golden, Avon, Breckenridge, Durango, Aspen, Basalt and Carbondale.

Hattie Johnson, Southern Rockies stewardship director for American Whitewater, said in a prepared statement that this is an incredible victory for river recreation.

“The Colorado River through Glenwood Canyon is an iconic stretch of whitewater that attracts residents and visitors from far and wide,” she said. “This was an important case to ensure the Colorado River, the heart of the Glenwood Springs community, will continue to be enjoyed well into the future.”

“The Homestake Partners (Aurora Water and Colorado Springs Utilities) and Glenwood Springs worked very hard over a long period of time to reach the negotiated conclusion embodied within the stipulated Decree entered by the Water Court,” read a prepared statement from Greg Baker, manager of public relations for Aurora Water.

Agreements with opposers

To get its water right, the city had to negotiate agreements with a long list of other water users and entities who opposed it, including the Colorado Water Conservation Board and Front Range water providers like Denver Water and Colorado Springs Utilities.

According to its decree, Glenwood Springs made allowances for future water rights that have not yet been developed.

A RICD water right’s power comes from its ability to place a “call.” In theory, once built, if the whitewater parks were not receiving the full amount of water they are entitled to, the city could “call out” other junior water rights users upstream, who would have to stop diverting water until the parks got their full amount.

But the decree includes a provision called “Yield Protection for New Water Rights,” which lays out restrictions on the city’s ability to call for its water during dry years. It allows 30,000 additional acre-feet of water to be developed over the next 30 years, which would be protected from a call above 1,250 cfs. As long as a new water rights holder could prove with real-time stream gauge monitoring data that they are not getting their full amount because of a call placed by Glenwood Springs for the 2,500 cfs amount, then Glenwood has to cancel the call.

This would kick in only in years when the 50% exceedance probability for streamflow in the Colorado River at Dotsero is less than 1.4 million acre-feet from April through June, according to forecasts from the National Resources Conservation Service. The provision would apply to water rights younger than Dec. 31, 2013, which is the appropriation date for the city’s water right.

Glenwood Springs also cannot use the RICD water right as the basis to oppose any future water development upstream on the Colorado River or its tributaries.

These agreements, which allow for some level of future water development by upstream parties that will not be subject to the restrictions created by a RICD, have been included in other recently completed RICDs, like Pitkin County’s whitewater waves in Basalt.

Water for recreation hard to secure

The backbone of Colorado’s of water law, known as prior appropriation, is the concept that older water rights get first use of the river. But even though RICDs have only been around for about 20 years and are therefore junior to major agricultural and transmountain diversions, RICDs still often end up making concessions to allow future water development.

That is partly because the CWCB is tasked with making sure RICDs, which help keep water in the river channel, don’t prevent the state from developing all the water it legally can under the Colorado River Compact.

“I think in a perfect world you would have a more clear delineation of recreational rights like this one,” said Bart Miller, healthy rivers program director for environmental conservation group Western Resource Advocates. “If they are applying for water, they should be treated the same as any other right, that is, when they come along, they get their place in line and they get water appropriate for that time.”

Securing water for recreation has proved challenging in Colorado, where agriculture and cities have long dictated water policy, even as river recreation represents a growing segment of the state’s economy.

In 2021, after being met with opposition, river recreation proponents scrapped a proposal that would have let natural stream features like a rapid secure a water right for recreation. A second proposal earlier this year that would have allowed municipalities to create a “recreation in-channel values reach” has also been tabled and will not be introduced at the legislature this session.

“That’s something I think we can aspire to, to have rights for recreation and the environment be on an even playing field with all the other rights in the state,” Miller said. “I think it’s really important to the state of Colorado to recognize and support recreational water rights and recreational uses.”

Aspen Journalism covers water and rivers in collaboration with The Aspen Times and the Glenwood Spring Post-Independent. This story ran in the March 6 edition of The Aspen Times and Glenwood Springs Post-Independent.

Editor’s note: The story has been changed to add that the City of Glenwood plans to build only one of the three potential whitewater parks; which one has yet to be decided.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.