By Jerd Smith

The federal agency that distributes electricity from hydropower plants in the Upper Colorado River Basin will ask its customers, including more than 50 here in Colorado, to help offset rising costs linked to Lake Powell’s inability to produce as much power due to drought.

The Western Area Power Administration (WAPA), which distributes Lake Powell’s electricity, is gathering public comments and asking its customers how best to cope with long-term drought conditions that have pushed Powell and other reservoirs to historically low levels.

As flows in the Colorado River have declined due to climate change and a 20-year megadrought, there is less water in its storage reservoirs and, therefore, less pressure to power the turbines, causing them to generate less electricity.

WAPA has had to nearly double the amount of extra power it has had to buy this year to ensure it can meet its contract obligations to its customers.

“It’s all bad news, but it isn’t necessarily unexpected,” said WAPA spokesperson Lisa Meiman.

WAPA power is among the most sought-after in Western states because it is sold at cost and because it is a renewable power resource, something highly valued in places such as Colorado, where utilities are working to reduce their reliance on fossil fuels.

WAPA often buys extra power if for some reason its customers’ electricity needs don’t match up with its hydropower production on a given day. It delivers power over a 17,000-mile transmission grid to six states and 5 million people.

But as flows in the Colorado River have shrunk, those purchases have become larger and more frequent.

Last year it bought an extra 413,000 megawatts of power. This year it has already purchased 833,000 megawatts of additional power, according to Meiman, and the agency expects that number to grow this year and likely again next year as the drought continues with no relief in sight.

This year, because of the power demands of the West’s growing population and the need for air conditioning to combat ultra-high temperatures, power costs are already soaring.

Last year WAPA paid $25 per megawatt for its replacement power, Meiman said. This year it is paying $33 per megawatt, a 30% jump.

In Colorado, WAPA sells power to some of the state’s largest electric utilities, such as Tri-State Generation and Transmission, as well as cities, small towns and rural electric co-ops.

“We’re watching the situation closely,” said Natalie Eckhart, a spokesperson for Colorado Springs Utilities, which is a WAPA electric customer and which also draws a significant portion of its water from the Colorado River system.

“The bottom line is we care about this on all fronts,” Eckhart said.

Few expected power generation at Lake Powell to decline so quickly. The Colorado River Basin serves seven U.S. states and 30 Native American Tribes. For months, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the Upper Colorado River Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming have been nervously watching what’s known as the minimum power pool level at Powell, the lowest elevation at which power can be produced, which is 3,490 feet. If the reservoir drops lower than that, all hydropower production will stop.

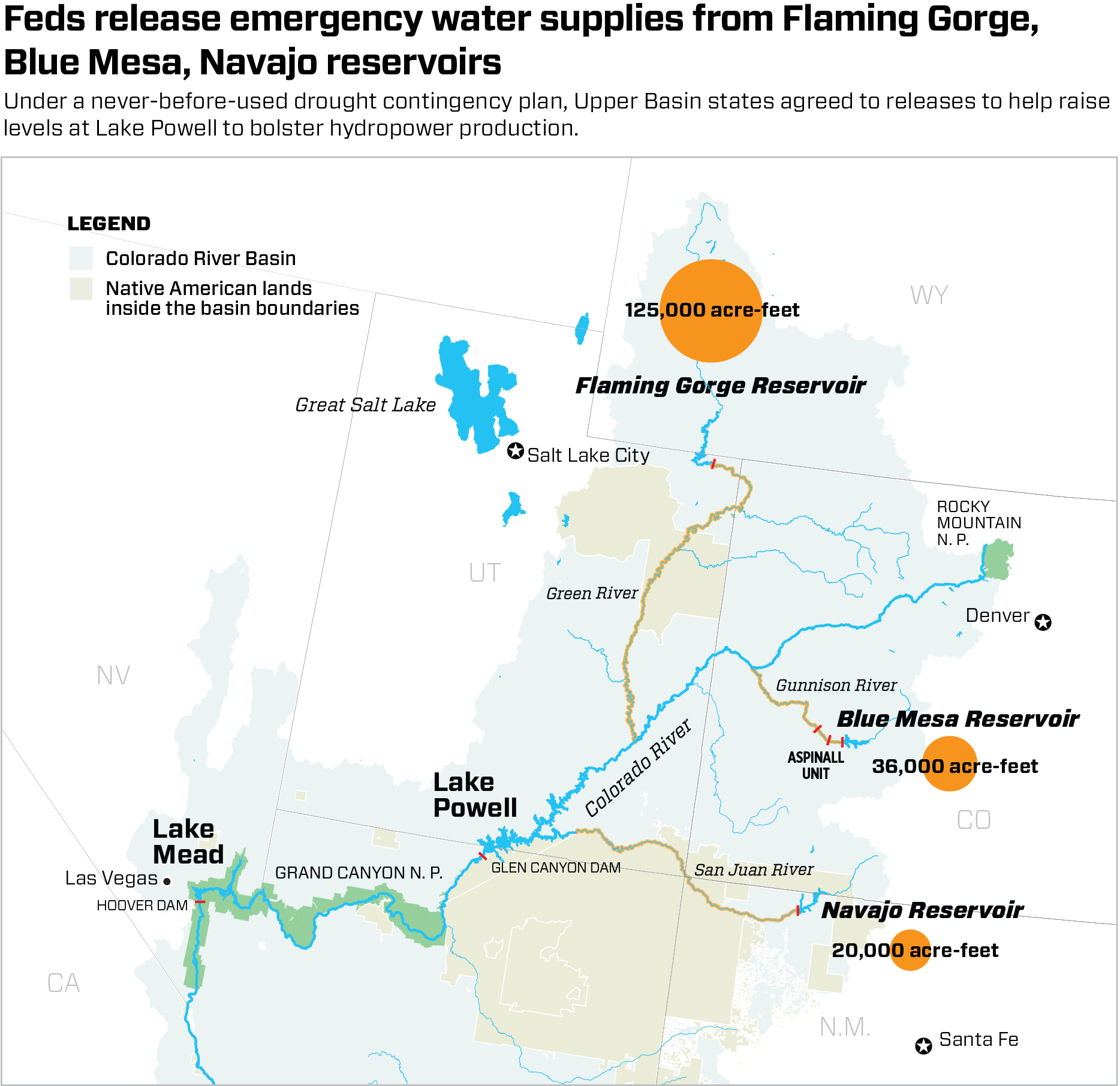

In July, as water levels at Powell continued to plummet, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, as part of the Upper Basin’s Drought Contingency Plan, began emergency releases of water from Utah’s Flaming Gorge, Colorado’s Blue Mesa, and New Mexico’s Navajo reservoirs to boost levels and protect Powell’s hydropower production.

And while those releases are expected to help keep the turbines functioning, the releases won’t be enough to restore them to full production, leaving WAPA little choice but to look at restructuring the way it sells power and to raise its prices.

WAPA is forecasting a 35% increase in its costs, but is working to minimize the impact on utilities that purchase its power and anticipates a 12% to 14% rate increase as early as December. Some utilities are preparing to buy power elsewhere, when possible, to reduce their costs.

Holy Cross Energy, a rural electric co-op based in Glenwood Springs that is also a WAPA customer, has spent years converting its power portfolio from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources including wind, solar and biomass, as well as hydropower.

While WAPA electricity comprises just 3% of its power portfolio, Holy Cross CEO Bryan Hannegan is worried that this renewable, low-cost power source is in jeopardy if flows from the Colorado River into Lake Powell continue to decline, as they are projected to do.

“It’s one of the cleanest and lowest-cost sources of power for a whole range of utilities,” Hannegan said. “It’s been a bedrock on which we built the West. For it not to be available … it’s a big deal.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the last name of the spokesperson for Colorado Springs Utilities.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.