By Gary Pitzer

Las Vegas, known for its searing summertime heat and glitzy casino fountains, is projected to get even hotter in the coming years as climate change intensifies. As temperatures rise, possibly as much as 10 degrees by end of the century, according to some models, water demand for the desert community is expected to spike. That is not good news in a fast-growing region that depends largely on a limited supply of water from an already drought-stressed Colorado River.

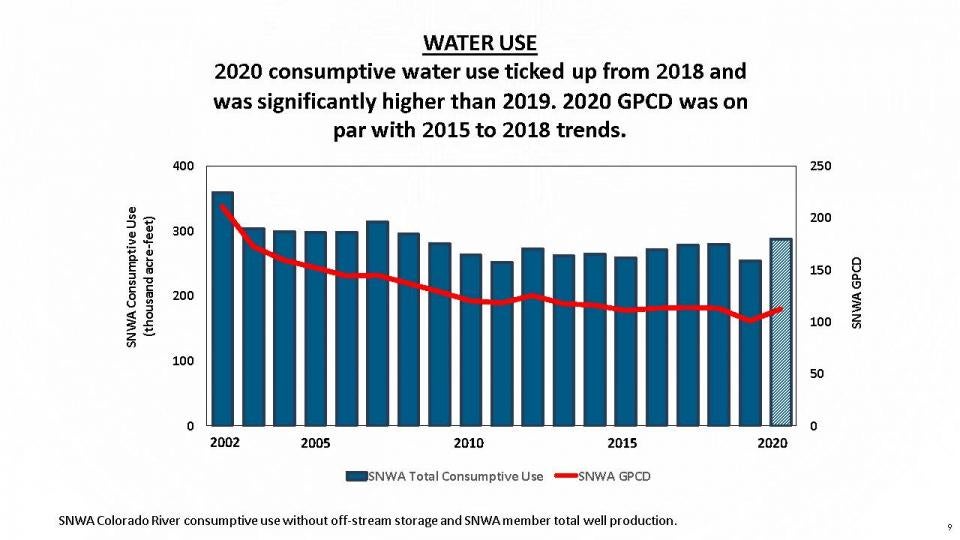

With this in mind, the Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA), the wholesale water provider to more than 2 million people in the Las Vegas metro area, is seeking to drive down daily per capita water use (now at about 112 gallons), through wide-ranging, innovative and permanent conservation methods. The goal is to reduce daily water use to 98 gallons by 2035, even as projections indicate per capita water use could increase by nine gallons a day as the climate warms.

Meanwhile, the Colorado River Basin plunges deeper into historic drought that seems certain to lead to water supply curtailments for Nevada and Arizona. Cities in the arid Southwest for years have sought to drive down water use to stretch supplies. Now, a warming climate, continued population growth and increased water demand have raised the stakes.

In response, SNWA aims to wring more water savings out of everything from ice machines and grassy medians to industrial cooling towers, an aggressive conservation effort that could provide examples for communities throughout the Southwest.

“We have been extremely successful helping the community embrace living in the desert and adopting a conservation mindset,” said Marilyn Kirkpatrick, chair of SNWA’s board of directors. “However, we have more work ahead to continue helping the community – especially new residents – use water as efficiently as possible.”

A warming basin

Arguably the hardest-working river system on Earth, the Colorado River helps meet the water needs of 40 million people, farms and ecosystems across a huge landscape. Premised on an annual flow that was overestimated and overallocated, the river is under extreme stress as climate change drives warming temperatures.

According to the Bureau of Reclamation’s January 2021 Colorado River Basin SECURE Water Act Report to Congress, 2000 to 2019 was the driest stretch in more than 100 years of record-keeping. Average annual temperatures are creeping up and the past 20 years were likely warmer than at any time in the past 2,000 years, the report said. Of the 20 warmest years on record, 17 have occurred since 1994. The trend shows no sign of abating.

A warming climate has major implications for water supply in the Colorado River Basin. A warmer atmosphere sponges up more water from the land surface and water bodies, leaving less to run off or flow to downstream reservoirs. Everything – people, wildlife and vegetation – is left thirstier.

Writing in their 2020 report, Climate Change and the Aridification of North America, climate scientists Jonathan Overpeck and Brad Udall explained the phenomenon of aridification: “Soils dry out in a straightforward manner understood by anyone gardening on a hot day, and they dry out faster the warmer it gets.”

Overpeck, at the University of Michigan, explained that hotter temperatures are robbing moisture from the Colorado River Basin. The drought in the Basin, he wrote in a May 18 Twitter post, “is really an ongoing temperature-driven aridification, that if combined with a true precip-dominated megadrought, will get much worse.”

SNWA’s 2020 Water Resource Plan notes that the impacts of climate change on water supply can no longer be considered as something that might happen later. Instead, “evidence supports the fact that climate change is happening now and that it will have a lasting effect on the availability of Colorado River water supplies.”

Already in the midst of a decades-long drought, conditions in the Colorado River Basin dramatically worsened in 2021, with record low inflows into the anchor reservoirs of Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Over the last 20 years, Lake Mead’s water level has dropped about 130 feet. As Mead’s level continues to fall, water supply reductions increasingly kick in.

Ensuring water security

Lake Mead, filled by Colorado River water, is Las Vegas’ mainstay. Ninety percent of the area’s water supply comes from the lake. Nevada’s Colorado River allocation is 300,000 acre-feet per year. In the past 10 years, SNWA’s take from Lake Mead has been about 445,000 acre-feet. However, factoring in the approximately 220,000 acre-feet of treated effluent returned to Mead each year means the average net consumptive use of Colorado River water has been 225,000 acre-feet.

SNWA’s water conservation campaign has helped cut its Colorado River consumption by about 23 percent between 2002 and 2020 even as 780,000 new residents arrived.

But the thermometer is inching up. Clark County, home to about 75 percent of Nevada’s population, is projected to warm by as much as 10 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century, according to SNWA. That means incorporating warming temperatures into water accounting with greater intensity and urgency.

“We have acknowledged that warming is going to go on in the valley for a very long time,” said Colby Pellegrino, SNWA’s deputy general manager for resources.

“Two years ago, we started taking a more serious approach to defining the conservation programs that would be necessary to meet our goal,” she said. “We have done a lot of work on what local temperature projections would look like in the future. While we’ve been making progress … there are going to be these upward pressures on demand occurring at the same time.”

Like some other Southwest cities that depend on the Colorado River, SNWA has an aggressive water conservation program that pairs education and outreach with financial incentives. The agency relentlessly pursues saving water wherever possible, from urging restaurant customers to forego the complimentary glass of drinking water (and all that gets saved as a result) to rebates for turf removal and ensuring the efficiency of all water-using machinery.

Kathryn Sorensen, director of research at Arizona State University’s Kyl Center for Water Policy in Phoenix, said Las Vegas and Phoenix have pursued similar approaches in that they are desert cities that emphasize certainty and the preservation of reliable water supplies.

“Both of these cities are held to a really high standard compared to other cities across the United States in terms of water security,” said Sorensen, who previously served as director of the city of Phoenix’s Water Services Department. “They are very risk-averse and spend a large amount of money and go through a very large effort to make sure that they are planning methodically for what might come.”

In Phoenix’s case, she said, that meant devising a water rate structure that charges users more for water in the summer than in the winter. Sorensen called it a “direct financial signal” for people to get rid of their lawns and lush landscaping without employing a rebate program. As a result, grass landscaping at single-family homes in Phoenix fell from about 85 percent in the 1970s to about 10 percent in 2021, she said, noting that turf for median strips has been prohibited since the 1990s.

Rewarding innovation

Southern Nevada’s hunt for water savings knows no limits. The uses may seem miniscule, but they add up. A glass of water not served at a restaurant saves about three gallons, when considering the amount used for dishwashing, ice production and filling the glass, said Patrick Watson, SNWA’s conservation programs administrator. SNWA subsidies for new ice machines at the region’s many golf courses saves 3 million gallons a year. The list goes on.

“We reward innovation,” Watson said. “If you have a project and it involves a new technology or an innovative way to save water, we’ll take a look at it.”

Case in point, the Ocean Spray bottling plant in Henderson. An engineer there devised a process in which industrial water is used three times during production before it gets sent out as wastewater.

“We never saw something like that before,” Watson said. “We studied it for six months, determined what the water savings was and ended up paying them an incentive.” Ocean Spray received $45,600 for saving 5.7 million gallons a year through that engineering change. Ocean Spray pursued two other water-saving innovations for which they were rewarded $27,000 by the agency, Watson said.

One of the big water users targeted for reduction are the evaporative cooling towers that keep Las Vegas’ commercial and industrial buildings cool. Transitioning that technology to other cooling processes such as air conditioning is one way to save water, more than two gallons per person per day, according to SNWA.

SNWA subsidizes tunnel washers, an amazing piece of hardware that uses less than a gallon of water per pound to wash 150 pounds of laundry in 90 seconds. Tunnel washers reduce the amount of water used per pound of laundry by three gallons, a considerable figure considering that commercial laundries in Las Vegas can wash as much as 1 million pounds of laundry each month.

The agency is now targeting homes that are on septic systems to connect them to the wastewater stream, where the effluent can be cleaned and reused or returned to Lake Mead.

Goodbye grass

One of the highest-profile conservation tactics is the war on turf. Outdoor landscaping is the single largest consumptive water user in Southern Nevada. Las Vegas’ desert environment is an unlikely place for lush, water-guzzling lawns more suited for the Midwest and East Coast. In the hot and dry West, average customer demand for water (mostly for outdoor irrigation) can be 50 to 80 percent higher than in the humid East, according to the Water Research Foundation. Limiting outdoor irrigation is critical in a region where 4 inches of rain is considered a good year.

Grass requires about 73 gallons per square foot, per year, while drip-irrigated landscaping only consumes about 18 gallons, according to SNWA.

The agency for years has preached that turf only belongs where it’s regularly used, such as in parks and athletic fields. In 2003, local municipalities in Southern Nevada adopted ordinances that prohibited the installation of grass in front yards of new homes and limited backyard grass to 50 percent of the area. Grass was also prohibited in commercial developments.

For yards with existing turf, SNWA pays homeowners $3 for every square foot of grass replaced with water-smart landscaping. The money applies to as much as 10,000 square feet per site per year and $1.50 per square foot thereafter. It’s a popular program that’s removed more than 4,500 acres of grass, amounting to about a quarter of the turf in the Las Vegas Valley, saving about 11 billion gallons of water every year. SNWA also offers incentives for installation of artificial turf on athletic fields.

Southeast of Las Vegas, the city of Henderson adds funds to the SNWA rebate to promote turf replacement for swaths as large as 40,000 square feet in commercial, industrial and multifamily housing areas.

“We know it’s important to replace natural turf in areas where it doesn’t make much sense… so we built our program to accelerate conversions there,” Henderson’s conservation supervisor Tina Chen said on SNWA’s Water Smarts podcast. “We believe the additional incentive will entice more businesses to participate and streamline their operating costs.”

Henderson’s assistance means participants can receive as much as $120,000 for those large conversions.

Now, the focus is on eliminating as much turf from Southern Nevada as possible, with an emphasis on reshaping parts of the urban landscape installed years ago and modeled after American communities much wetter than Las Vegas.

A bill passed by the Nevada Legislature and signed into law in early June will prohibit Colorado River water from being used to irrigate ornamental grass on non-residential properties starting in 2027. Of the more than 12,000 acres of turf in the Las Vegas Valley, 5,000 is considered nonfunctional.

“It’s only being walked on by the person that’s mowing it,” said Pellegrino, SNWA’s deputy general manager for resources.

Clinging to turf

While turf removal has been successful, enthusiasm for it may be waning, said Tom Warden, senior vice president with Summerlin, the largest master planned community in Nevada. Warden, a Las Vegas resident of more than 30 years, said a renewed emphasis is necessary because water rates are likely to jump and SNWA’s rebate will eventually vanish.

“It is safe to say there are folks who resist it,” said Warden, who interacts with the homeowner associations and sub associations that are part of the 22,500-acre Summerlin development. He said initially many people didn’t like the idea of not having turf everywhere, but they have come to accept the much-improved desert landscape designs.

“Southern Nevadans understand that we all have to embrace a more sustainable approach,” he said. “They are getting the picture. It’s the growth of stewardship.”

Still the conservation ethic has changed significantly since the days before the drought when Lake Mead was full and spilling water.

Back then, “nobody was thinking about conservation,” Warden said. “They were building other master planned communities that were wall-to-wall turf without a thought.”

But ornamental turf is still a part of many neighborhoods.

“Homeowner’s associations in Southern Nevada are still watering more than 64 million square feet of non-functional turf,” SNWA’s Watson said. “That’s close to five billion gallons of water every year to maintain grass for purely visual effect.”

SNWA’s turf replacement has reached residents but business participation has been more challenging, SNWA spokesman Bronson Mack said. Many owners of business parks, strip malls and shopping centers are out of state and disconnected from the community.

“They don’t hear the same conservation messages on a regular basis, and they are not attuned to desert living or the need to replace grass,” Mack said.

The road ahead

Climate change and the plummeting Colorado River, where a 20-plus year drought is forcing unprecedented adaptation measures, are pushing desert cities toward more aggressive water management. Anticipating drier times, SNWA in 2015 took the extraordinary step of building a third intake deeper into Lake Mead, at a cost of nearly $1 billion, to ensure it could continue to draw water from a dropping reservoir. Phoenix spent $500 million to move Salt and Verde River supplies to areas of its service territory that historically have been entirely dependent on the Colorado River.

The actions signal that both cities are able to ensure reliable water deliveries, come what may on the Colorado River, said Sorensen, with Arizona State’s Kyl Center. Increased demand management and extended use of recycled water are areas “where there’s still a lot that can be done.”

John Berggren, water policy analyst with Western Resource Advocates in Boulder, Colo., said that as municipalities realize their irrigation demand is going to go up because of warming temperatures and their water is becoming scarcer, they’ll begin taking a hard look at landscapes to see what’s expendable. It’s important to note that the effort doesn’t stop with getting rid of ornamental turf.

Berggren said more attention is being focused on gray water reuse, where types of household wastewater from dishwashers, sinks and the like can be used to irrigate outdoor landscaping.

“All communities around the West can find more ways to be water efficient, both on the indoor and outdoor side of things,” he said. “The banning of non-functional turf is a great step on an already well-developed conservation path for Nevada, but the path is long, and I hope they continue to push the envelope. I hope more states and more water providers take that step.”

Halting irrigation to ornamental turf can free up quite a bit of water that provides a cushion for future growth, Berggren said, and even allows for putting water back into rivers.

Kirkpatrick, chair of the SNWA board, said it’s up to community leaders to push the water conservation message and get people to participate in rebate programs.

“We’ve made a lot of very impressive gains over the past 20 years, but we have more work to do, she said. “Any efforts on the part of Clark County and other municipalities to implement policies that increase sustainability will help us meet the challenge together.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @GaryPitzer

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.

This article was supported in part by a grant from The Water Desk, an independent journalism initiative based at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism, and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.