The first automated dust-on-snow monitoring technology in the mountains of Northwest Colorado is expected to be installed this fall to study the impact of dust from arid landscapes on downwind mountain ecosystems in the state and in Utah.

McKenzie Skiles, who is a hydrologist and a University of Utah assistant professor, will use close to $10,000 from a National Science Foundation grant to purchase four pyranometers, which measure solar radiation landing on, and reflected by, snow.

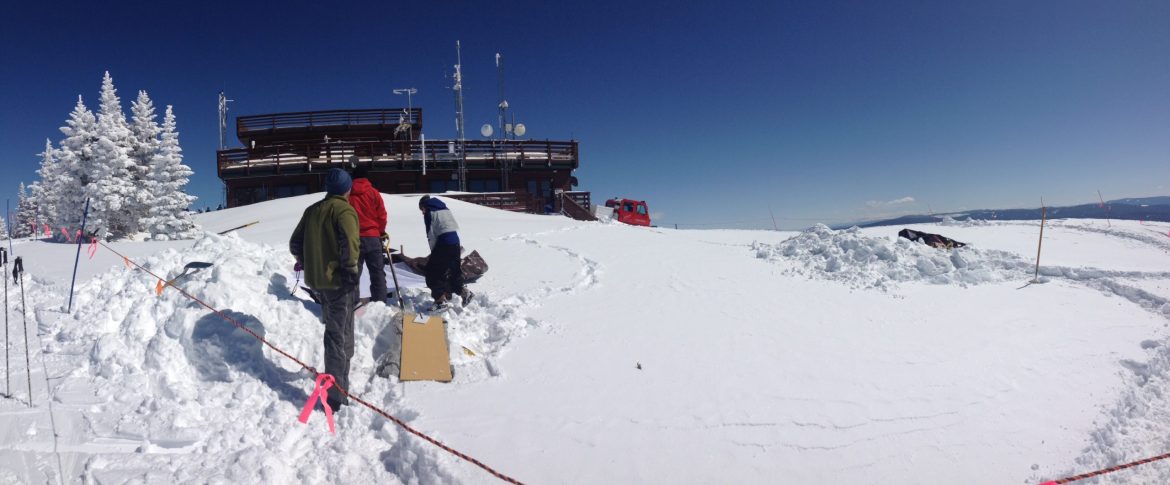

These instruments will be placed on a data tower at Storm Peak Lab, a research station above Steamboat Springs that studies the properties of clouds, as well as natural and pollution-sourced particles in the atmosphere. The lab sits at 10,500 feet near the peak of Mount Werner at the top of Steamboat Resort in the Yampa River basin. Starting next winter, live information will be transmitted to MesoWest, a data platform at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

This station will be the latest added to a growing network of dust-on-snow monitoring towers across the state and Utah. Such stations offer key insights to researchers studying how dust impacts the timing and intensity of snowpack melt, Skiles said.

“My goal is to have a network of dust-on-snow observation sites that spans a latitudinal gradient in the Rockies and headwaters of the Colorado River,” Skiles said.

Five towers spread around Colorado and Utah currently take in data on the solar energy absorbed and reflected by the snow. Dust particles darken the snow’s surface then absorb more energy than clean snow does. Such a process changes light frequencies recorded by the pyranometers. Researchers take this frequency data and run it through models to quantify how much surface dust heats snow and speeds snowmelt.

Of the currently operating stations, one is near Crested Butte; one sits on Grand Mesa above Grand Junction; two are near Silverton; and one is in the Wasatch Mountains near Alta, Utah. The sites are run, respectively, by Irwin Mountain Guides; by the U.S. Geological Survey and a collaborative user group; by the nonprofit Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies; and by University of Utah researchers.

Stations were first established in the Senator Beck Basin, near Silverton in the San Juan Mountains, which is the Colorado range most immediately downwind from the deserts of the Colorado Plateau and receives the first dust — and the most dust. In analyzing data from the two radiation towers there, Skiles and colleagues revealed that dust on snow shortened the cover by 21 to 51 days and caused a faster, more-intense peak-snowmelt outflow. In a 2017 study that also analyzed data from Senator Beck Basin, Skiles showed that it was dust, not temperature, that influenced how fast snowpack melted and flowed into rivers downstream.

The Steamboat station will fill a gap in the locations of radiation towers, Skiles said.

“We know that a lot of dust comes from the southern Colorado Plateau and impacts the southern Colorado Rockies, but we don’t understand dust impacts as well in the northern Colorado Rockies,” she said.

Since there isn’t a data station in the northwest portion of the state, “The only way to know if there’s dust there is to go and dig a snow pit,” said Jeff Derry, executive director of the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies.

CSAS runs the Colorado Dust on Snow program, or CODOS, which includes the two radiation towers in Senator Beck Basin.

Three times a year, usually in mid-March, April and May, CSAS staffers tour Colorado, digging snow pits at mountain locations to assess dust conditions statewide. Since dust events continue into May, this year’s conditions are currently hard to quantify, Derry said.

So far, this spring has been dustier than 2020; five dust events have hit the Senator Beck Basin as of April 14, compared with the three total dust events last year. As in years past, Senator Beck Basin has experienced more dust events than have the sites to the northeast, according to Derry in the latest CODOS update. Yet, a recent April storm distributed dust on all sites in the state.

Unlike the past few years, Rabbit Ears Pass — the CODOS sampling site closest to Steamboat Springs and located northwest of Bear Mountain along U.S. Highway 40 — has received at least as much dust as the Senator Beck Basin has, according to the CODOS update. As of the April 12 to 14 CODOS tour, two dust layers of moderate severity are present on the pass. That amount probably came from storms in the Uintah basin, in the Four Corners region and in Mexico’s Chihuahuan Desert, Derry said.

These dust layers will warm the snow and have an impact on snowmelt timing this runoff season, Derry said. In order to quantify that effect, radiation data from dust-on-snow study plots, like the one planned for Storm Peak, is needed.

Dust in arid landscapes — often disturbed by human activity — travels in wind currents during storms and is deposited on downwind mountains, Skiles said. The number of dust events and mass of dust carried in storms vary from year to year depending on wind speed, the intensity of drought and the frequency of human activities that disturb surface soils, said Janice Brahney, an assistant professor at Utah State University who studies nationwide dust composition and deposition patterns.

For instance, Senator Beck Basin experienced a peak in dust events from 2009 through 2014 and a decline in recent years. This decline is probably due to storms and winds that are not strong enough to carry and deposit dust into Colorado mountains, Brahney said.

“My sense is that a lot of the storms that are occurring in the southern United States are still occurring — they’re just not always reaching Colorado,” she said.

Dust data will provide future insights for Steamboat water policy and management.

Skiles’ lab isn’t the only entity interested in the Storm Peak Lab dust-on-snow data. Kelly Romero-Heaney, water resources manager for the city of Steamboat Springs, anticipates using the data in the city’s next water-supply master plan.

“We update our water supply master plan at least every 10 years,” Romero-Heaney said. “So, even if it’s another eight years of data that’s needed before we can see measurable trends, by the time we update our models, we’ll be able to integrate that data.”

The most current plan, released in 2019, includes forecasts for Steamboat Springs’ water supply 50 years into the future. The plan — factoring in historic streamflow data and stressors to water supply such as climate change, wildfire and population growth — concluded that the city will meet its demands through 2070.

“One thing we’re fortunate in is that we have a relatively small community for a relatively large snowy water basin,” Romero-Heaney said.

Mount Werner Water and Sanitation District supplies the city with its water, derived primarily from Fish Creek and Long Lake reservoirs, said District General Manager Frank Alfone. In the summer months, the district also treats water from the Yampa River to meet irrigation demands, he said.

In order to predict Fish Creek and Long Lake reservoir levels, Alfone relies on data from the Buffalo Pass snowpack station, which is run by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, and on monthly water-supply forecasts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association.

Alfone says dust on snow and the city’s water supply have “an impact now and more so in the future,” Alfone said.

Indeed, dust levels are expected to rise throughout the West. A 2013 study revealed that since 1994, dust deposition has increased in the region, with the majority of dust lifting from deserts in the Southwest and West, along with regions in the Great Plains and Columbia River Basin. This increase, according to the study, is probably due to heightened human disturbance of dry soils, which includes off-road-vehicle use, gas drilling, grazing and agriculture.

Increasing dust accelerates snowpack entrance into rivers, Skiles said. This earlier runoff lengthens the period when water can evaporate from rivers and lower streamflow, impacting water supply in the warmer months, according to her study,

“What we’re finding is that runoff is happening earlier and earlier each year, and that has real implications for us come August and September, particularly if we get very little rain throughout the summer season,” Romero-Heaney said.

Data from the widening dust-on-snow-monitoring network will aid water-resource managers and researchers in predicting how dust will shape future snowpack across Colorado.

“Dust does play a really significant role in hydrology. And that’s really important in the Western states, where we rely on the mountain snowpack not just for our own drinking water, but for our own functioning ecosystem,” said Brahney, lead author of the 2013 dust study.

“We anticipate some challenges for the whole basin, although we will still be able to reliably supply our customers with drinking water,” Romero-Heaney said.

This story ran in the Steamboat Pilot & Today on April 23.