By Heather Sackett

RANGELY — As its trial date in water court approaches, hundreds of pages of depositions obtained by Aspen Journalism reveal state engineers’ sticking points regarding a proposed reservoir project they oppose in northwest Colorado.

Over a few days in November, state attorneys subpoenaed and interviewed several expert witnesses and the Rio Blanco Water Conservancy District manager in the White River storage-project case, also known as the Wolf Creek project. Their questions centered on the town of Rangely’s water needs and on whether water is needed for irrigation.

The documents, obtained through a Colorado Open Records Act request, also underscore the extent to which fear of a compact call is shaping this proposed dam and reservoir project between Meeker and Rangely.

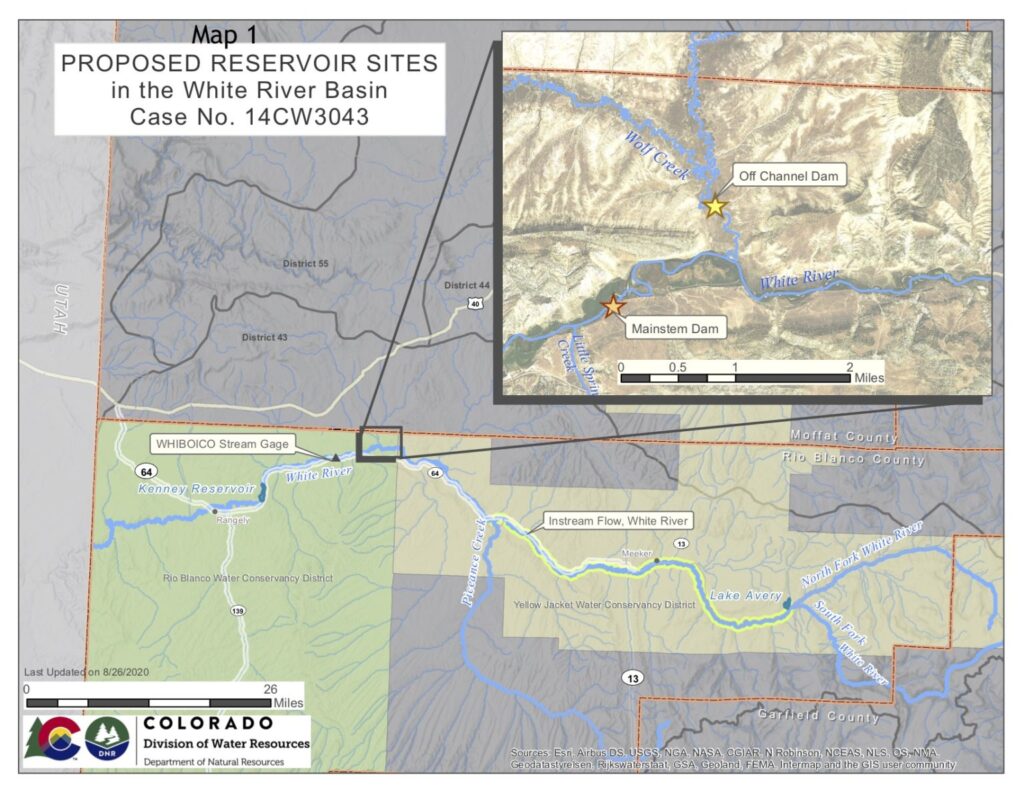

The Rangely-based Rio Blanco Water Conservancy District is applying for a conditional water-storage right to build a 66,720-acre-foot, off-channel reservoir using water from the White River to be stored in the Wolf Creek drainage, behind a dam 110 feet tall and 3,800 feet long. It would involve pumping water uphill from the river into the reservoir.

There also is an option for a 72,720-acre-foot on-channel reservoir, although this scale of project is now rare in Colorado. Rio Blanco has said they prefer the off-channel option.

For more than five years, top state water engineers have repeatedly said the project is speculative because Rio Blanco has not proven a need for water above its current supply.

Despite Rio Blanco reducing its claim for water by more than 23,000 acre-feet from its initial proposal of 90,000 acre-feet, state engineers still say the water-right application should be denied in its entirety. After failing to reach a settlement, the case is scheduled for a 10-day trial in January. Division 6 Engineer Erin Light and top state engineers Kevin Rein and Tracy Kosloff are the sole opposers in this case.

Irrigation needs?

A main point of contention between Rio Blanco and state engineers is whether there will be an increased need for irrigation water in the future. Rio Blanco claims it needs 7,000 acre-feet per year for irrigation.

During the depositions, state attorneys questioned Rio Blanco manager Alden Vanden Brink about the need for irrigation water. He claimed there is a local boom in agriculture and that there is high-value farmland that is not being irrigated simply because of a lack of water. Vanden Brink said happiness for residents on the lower White River will increase with access to irrigation water from the proposed reservoir, adding that if irrigation water is made available, demand for it will increase.

“It will make water available in the lower White River so that people can increase their quality of life and have a garden, you can have a few pigs,” Vanden Brink’s deposition reads. “It’s just going to be improvement all the way around.”

But details were sketchy on what specific lands would be irrigated and the district’s plan to get water from the reservoir to irrigators. State engineers, in a subsequent trial brief, say that just because there are lands that might benefit from irrigation doesn’t mean there will be future increased demand. If you build it, they won’t necessarily come.

“Instead, the premise that there will be a demand for water if the water right is granted is exactly the sort of ‘self-fulfilling prophecy of growth’ prohibited under Colorado’s anti-speculation doctrine,” the state’s trial brief reads.

Engineers also say Rio Blanco has not identified how the reservoir, situated low in the White River basin, would serve the majority of irrigated acres located upstream.

Rangely’s water needs

Rio Blanco and the state also disagree about the amount of water needed for Rangely, a high-desert town of about 2,300 people near the Utah border. Rangely takes its municipal water from the White River.

In their depositions, Vanden Brink and Gary Thompson, an expert witness and engineer with W.W. Wheeler and Associates, refer to “cow water” as the source of Rangely’s water issues.

According to Vanden Brink, who also is the town’s former utilities supervisor, when flows in the White River drop to around 100 cubic feet per second, water quality becomes impaired. That can include increased algae growth, decreased dissolved oxygen, increased alkalinity and increased mineral contaminants, which require more treatment, he said.

“If you want to look at that water and how you can take that water and make it potable, forgive me, but it looks worse than cow water,” Vanden Brink said in his deposition. “I know if I was a cow, I wouldn’t want to drink it. It’s pretty degraded; it’s pretty muddy, it’s bubbly, it’s gross. And there’s a reason Rangely’s got the extensive treatment that it does.”

In an April letter to Rio Blanco, Town Manager Lisa Piering and Utilities Director Don Reed said Rangely would commit to contract for at least 2,000 acre-feet of storage for municipal use after the reservoir is built. According to expert reports, Rangely’s current demands are 784 acre-feet per year.

Project proponents say that increased flows from reservoir releases will dilute contaminants and improve water quality at the town’s intake.

But this argument doesn’t work for state engineers, who say that the water Rio Blanco says Rangely needs is not based on projected population growth and that Rio Blanco has not analyzed whether the town’s existing water supplies would be sufficient to meet future demands.

Colorado River Compact influence

Depositions and water court documents reveal how water managers’ and experts’ fear — and expectation — of a compact call could influence the project proposal.

According to the 1922 Colorado River Compact, the upper-basin states (Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming) must deliver 7.5 million acre-feet a year to Lake Powell for use by the lower-basin states (Arizona, California and Nevada). If the upper basin doesn’t make this delivery, the lower basin can “call” for its water, triggering involuntary cutbacks in water use for the upper basin.

Water managers and policymakers admit that no one knows how it would play out just yet, but risk of this hypothetical scenario becoming reality is increasing as drought and rising temperatures — both fueled by climate change — decrease flows into Lake Powell.

Water managers are especially worried that those with junior water rights, meaning those later than 1922, will be the first to be curtailed. Senior water rights that existed prior to the compact are generally thought to be exempt from compact curtailment.

Many water users in the White River basin, including the towns of Rangely and Meeker, have water rights that are junior to the compact, meaning the users could bear the brunt of involuntary cutbacks in the event of a compact call.

Rio Blanco is proposing that 11,887 acre-feet per year be stored as “augmentation,” or insurance, in case of a compact call. Releasing this replacement water stored in the proposed reservoir to meet these compact obligations would allow other water uses in the district to continue and avoid the mandatory cutbacks in the event of a compact call.

According to Rio Blanco’s trial brief, “there is significant risk of a compact curtailment in the next 25 years that could negatively impact 45% of the water used in the district.”

In his deposition in response to questions from Rio Blanco attorney Alan E. Curtis, Thompson said drought scenarios will get worse in the future, the White River will be more strictly administered and a compact call is likely to occur.

“Things are — in my opinion — drought conditions are increasingly pervasive,” he said.

But state engineers say that augmentation use in the event of a compact call is not a beneficial use under Colorado water law and is inherently speculative. Compact compliance and curtailment are issues to be sorted out by the Upper Colorado River Commission and the state engineer, not individual water users or conservancy districts, they say. The state of Colorado is currently exploring a concept called demand management, which could pay water users to use less water in an effort to boost levels in Lake Powell.

According to their trial brief, state engineers say that while the desire to plan for compact administration is understandable, “the significant uncertainties involved in future compliance under the Colorado River Compact mean that Rio Blanco cannot show a specific plan to control a specific quantity of water for augmentation in the event of compact curtailment.”

The trial is scheduled to begin Jan. 4 in Routt County District Court in Steamboat Springs. Among the witnesses that Rio Blanco plans to call are Colorado River Water Conservation District Manager Andy Mueller, Colorado Water Conservation Board Chief Operating Officer Anna Mauss and Rio Blanco County Commissioner Gary Moyer.

Aspen Journalism is a local, nonprofit, investigative news organization covering water and rivers in collaboration with The Aspen Times and other Swift Communications newspapers. This story ran in the Dec. 26 edition of The Aspen Times and the Vail Daily, and the Dec. 28 edition of Steamboat Pilot & Today.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism. The Water Desk is seeking additional funding to build and sustain the initiative. Click here to donate.