By Lynne Peeples, Ensia

November 11, 2020 — Editor’s note: This story is part of a nine-month investigation of drinking water contamination across the U.S. The series is supported by funding from the Park Foundation and Water Foundation. View related stories here.

From his back deck, Bogdan Marian can see the scars running down into the San Lorenzo Valley: the pad of a destroyed home, the scorched brown trees at the ridge line.

Marian is grateful to have a standing home. Yet his family and many others in the area still face another worry: the safety of their tap water. After fires marred the valley near Santa Cruz, California, in August, the local water district issued a “Do Not Drink Do Not Boil” notice to residents.

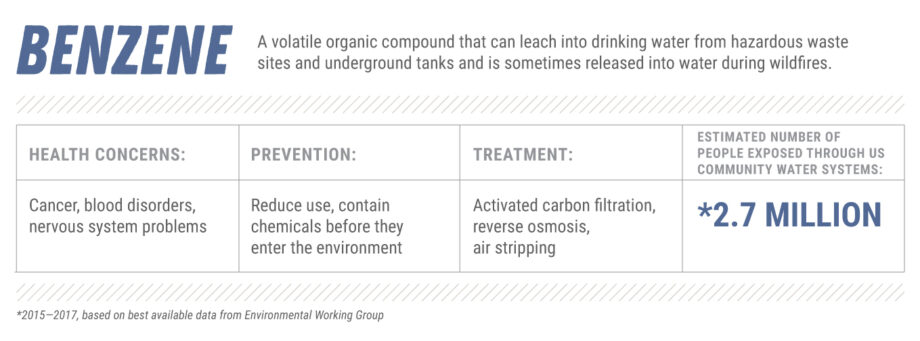

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) including benzene, residents were warned, could be seeping into the water system — just as the toxic chemicals did in Santa Rosa and Paradise, California, in the wake of wildfires in 2017 and 2018.

“I have an 18-month-old,” adds Marian. “I don’t want to expose him to anything questionable. So, we went several weeks after that using bottled water for basically everything including showering, cleaning, watering plants.”

Pervasive Chemicals

VOCs are a large group of chemicals that share an ability to vaporize in air and dissolve in water. Since the 1940s, they have been widely used in industry, agriculture and homes. They are components of gasoline, glues, degreasers, dry cleaning fluids, pesticides plastics and more. In addition to the notorious threat they pose to indoor air quality — off-gassing is common from new cabinets or laminate flooring, for example — VOCs can also find their way into the environment, tainting soil and water.

While VOCs that migrate into surface waters tend to evaporate, VOCs that travel through the soil and into groundwater can stick around and, ultimately, contaminate drinking water supplies. Most community water systems and private wells in the U.S. use groundwater. And given the scale of VOC use and frequent large releases into the environment, as well as their persistence and potential to harm human health, these chemicals remain a serious threat to America’s drinking water.

An assessment published by the U.S. Geological Survey in 2006 detected VOCs at the 0.2 microgram-per-liter level in nearly one-fifth of aquifers tested. The chemicals commonly seep into systems via spills and improper disposals. Benzene, for example, can enter groundwater from a gasoline or oil spill on the surface or from leaking underground fuel tanks. Similarly, many VOCs, including perchloroethylene (PCE) and trichloroethylene (TCE), have been known to leach into groundwater from dry cleaners, as well as electronics and aircraft manufacturing or maintenance.

However VOCs get into drinking water, it can be bad news. “If you’re talking about something like lead in the water, you want to avoid drinking it. If you’re talking about VOCs, then you really don’t want to get those on your skin. Even a dishwasher creates vapor that could be inhaled,” says Gina Solomon, a program director with the Public Health Institute in Oakland, California.

Research has linked exposure to VOCs with increased risks of health effects including anemia, leukemia, kidney cancer, reproductive problems, birth defects and nervous system damage.

In general, children are at greatest risk from exposure to VOCs, explains Solomon. They take in a greater amount of fluid proportional to their body weight, compared with adults. And they have a lot more relative skin surface for their small size, resulting in a higher dose if bathed in the water.

“Benzene is also notorious for delayed health effects,” says Solomon. “The younger you are the more likely you are to live long enough to encounter those health effects.”

Wildfire Connection

Wildfires as a source of VOCs in drinking water had not really been on the radar until the Tubbs Fire burned through large swaths of Santa Rosa, California, in 2017. After the blaze, drinking water samples from municipal supplies had levels of several VOCs, including benzene, above state and federal exposure limits.

The next year, the Camp Fire devastated the town of Paradise, California. Benzene and other VOCs popped up in drinking water teststhere, too.

What tests uncovered after wildfires scorched the San Lorenzo Valley in late August, including one water sample with benzene levels at more than 40 times the state water board’s drinking water standard, “reinforced what we had found previously,” says Daniel Newton, an assistant deputy director with the California Environmental Protection Agency’s State Water Resources Control Board. “As the magnitude of fires is increasing and causing larger impacts to communities and water systems concurrently, we’re seeing more and more of these VOC detections. This year is setting a new pace for us.”

Solomon notes that benzene is known to cause cancer in humans. “It’s an alarming thing to find,” she says.

And benzene was just one of several VOCs detected in various water samples collected after the fire.

Marian recently learned about the drinking water contamination resulting from the earlier fires. And he laments that there still doesn’t appear to be a “playbook” for protecting water resources from wildfires. “I don’t think we’ve caught up to the things we’re learning from the 2017 and 2018 fires,” he says. “And we still don’t really understand how contamination happens. We just know it’s related to fire.”

Melting Plastics, Losing Pressure

No one knows for sure why VOCs are showing up in drinking water in the aftermath of fires. But a few ideas have emerged.

Plastic pipes and other plastics in the water system can melt or burn during a fire, releasing VOCs that could directly dissolve into the drinking water. In Paradise, scientists found globs of melted plastics in portions of the water service line. Chemicals from plastics may also absorb into pipes as they pass through, and then leach back into the water over time. “But I haven’t seen evidence yet that plastics are solely responsible for contamination after wildfires,” says Andrew Whelton, an associate professor of civil engineering and environmental and ecological engineering at Purdue University.

Another hypothesis is that when a water system loses pressure due to fire damage, then smoke, ash and gases can get sucked into underground pipes and circulated throughout a water distribution system. Even without a fire, depressurization can cause bacteria and other contaminants to get into the water, notes Stefan Cajina, the north coastal section chief of the California water board’s Division of Drinking Water.

It’s possible that the presence of plastics and a loss of pressure may both be to blame. Whelton says he is doing tests to find the cause of the contamination.

Historical Threats

Victims of California wildfires are not the first in the U.S. to be threatened by VOC-contaminated drinking water.

Military bases have been one notorious source, says Richard Luthy, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University.

Take, for example, Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. Between the late 1950s and the mid-1980s, the drinking water on the marine base was tainted with toxic industrial chemicals including benzene, TCE and PCE, from waste disposal practices at an off-base dry cleaner as well as leaking underground storage tanks and industrial spills. Military veterans who served at the base during this time and developed certain diseases, such as kidney cancer or Parkinson’s disease, may now qualify for disability benefits through the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

VOCs were also the suspected villains in an unusual number of childhood leukemia cases in Woburn, Massachusetts, between 1969 and 1986. Well water had been contaminated with TCE and PCE, likely from industrial waste. A landmark lawsuit resulted in the responsible corporations contributing to the costs of remediation.

Still today, VOCs find their way into drinking water systems around the country. In Paden City, West Virginia, PCE levels in drinking water reportedly registered at almost three times the federal limit in January 2020. In August, officials detected 1,4-dioxane in a community water system in Springfield, Illinois.

Regulatory Lessons

The EPA regulates 21 VOCs under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Community water systems are required to monitor for these chemicals and, if their tests detect levels greater than the maximum contaminant level set by the EPA, they must inform their customers of the violation and take steps to remedy the situation. Still, Solomon and Whelton suggest the EPA’s regulations may not go far enough to protect the public from VOC contamination.

Methylene chloride, a VOC that appeared at levels above EPA limits in both Santa Rosa and Paradise, illustrates one potential reason. Federal and global health agencies consider it a probable human carcinogen. But standard drinking water testing might very well miss it. That’s because EPA requires that water systems test at the tap for lead and copper, but other tests for contaminants are done at the water treatment plant, explains Solomon. She notes a hypothesis that methylene chloride can form from a reaction among water pipes, disinfection byproducts and chlorine — contaminating water after it leaves the plant.

Other chemicals might be contaminating water systems after a fire, too. “We look for benzene, styrene, naphthalene. But we don’t actually know what chemicals we should be looking for,” says Whelton. He suggests that water testing using current EPA methods is not capable of detecting all of the chemicals found after the recent California wildfires.

Whelton further notes that government regulations for VOCs are based on long-term exposures and, therefore, generally don’t account for short-term, high-level exposures that can occur during a disaster such as a wildfire. And even when federal and state governments respond to a chemical disaster, they may fail to consider all of the potential routes of exposure. After a major industrial chemical spill in West Virginia in 2014, for example, efforts to protect residents from contaminated tap water relied on a U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention screening level for the main compound of interest, a VOC called MCHM, based on ingestion alone. Inhalation of vapors and skin absorption are also critical potential routes of VOC exposure, argues Whelton.

“This is why we have a ‘Do Not Boil’ advisory,” he adds, noting that boiling water can send VOCs into the air. Based on evidence from the Tubbs and Camp fires, he recommends that water systems issue a “Do Not Use” order for their customers that allows use of the water solely “for firefighting purposes and toilet flushing.”

“We have lots of regulations on drinking water, but they are designed for conditions in which the source of the water is considered pretty clean and you haven’t had an immediate natural disaster.” – Richard Luthy

His other advice: Begin widespread sampling after a fire and rush those samples to be tested within 24 hours. Until tests confirm what chemicals are in the water system, don’t allow people to be exposed to that water. And then flush the water distribution system to make sure soot and other debris don’t sit around furthering VOC contamination.

Luthy also recommends that the government provide guidance to help utilities — particularly small ones — “get back in business” after a wildfire, hurricane or the like.

“We have lots of regulations on drinking water, but they are designed for conditions in which the source of the water is considered pretty clean and you haven’t had an immediate natural disaster,” he adds. “Do we need to have some other ways to address the safety of water after a natural disaster? I say, ‘Yes.’”

Cleaning Up

Increases in testing, largely resulting from recent awareness of their potential presence after wildires, along with improved treatment technologies in recent years means VOCs are less likely to reach the tap. Among the popular treatment tools are activated carbon filters that can absorb the chemicals and a process called air stripping, which can remove or “strip” benzene and other VOCs by contacting clean air with the contaminated water. The air movement causes the chemicals to evaporate at a faster rate. Such a system was installed to clean up industrial contaminants in California’s San Fernando Valley. Luthy notes that air stripping is the go-to method for cleaning up groundwater polluted by gasoline stations.

That said, both testing and effective treatment technologies come at a cost. “As soon as we start talking about private wells and small water systems, all bets are off,” says Solomon, referring to the tight budgets and limited staff generally available in these situations to invest in testing and treatment. “The dollar signs start piling up when you start testing that well. And in order to ensure your well is safe you really have to test periodically. If there are no contaminants today, that doesn’t necessarily mean there will be no contaminants a year from now.”

She notes that many homeowners and very small water systems simply skip the testing, especially with limited regulations holding them to do it.

A lot of homes so far affected by 2020 wildfires have been in areas with private wells or small to very small systems. “Those systems are getting some help from the state,” says Solomon, noting that residents in Paradise and surrounding areas also benefited from an emergency federal grant for free testing. “But that’s not typical.”

Of course, prevention is a more effective tool than any testing or treatment. Whelton suggests that communities adopt building codes that require the installation of fire-resistant water meter boxes placed a safe distance from vegetation, for example. Water meters with minimal plastic components would be less likely to ignite. Whelton also recommends water main shutoff valves and sampling taps at every water meter box, which could help responders quickly determine water safety. And to block contamination from flowing from a damaged building into a larger pipe network, he advises the use of one-way valves, also known as back flow prevention devices.

The San Lorenzo Valley Water District took many preemptive steps to mitigate the potential threat to the region’s drinking water. It shut down part of its system before the wildfire’s arrival. A one-way valve also separates the neighborhood of Riverside Grove, one of the communities in which benzene was found, from the rest of the water system.

The “Do Not Drink Do Not Boil” notice has now been lifted for Marian’s neighborhood. But Marian remains cautious until more tests are done. “I’m comfortable enough to use tap water for laundry and cleaning the house,” he says. “But out of an abundance of caution, we’re still using bottled water for drinking and cooking.”

This story originally appeared on Ensia on November 11, 2020.