By David O. Williams

RED CLIFF — The U.S. Forest Service has been inundated with more than 500 online comments — the vast majority in opposition — to a geophysical study and drilling by the cities of Aurora and Colorado Springs to determine the feasibility of a second reservoir in the Homestake Creek drainage, including objections from nearby towns and a local state senator.

The geophysical study and the drilling are the next step in the lengthy process of developing a reservoir on lower Homestake Creek.

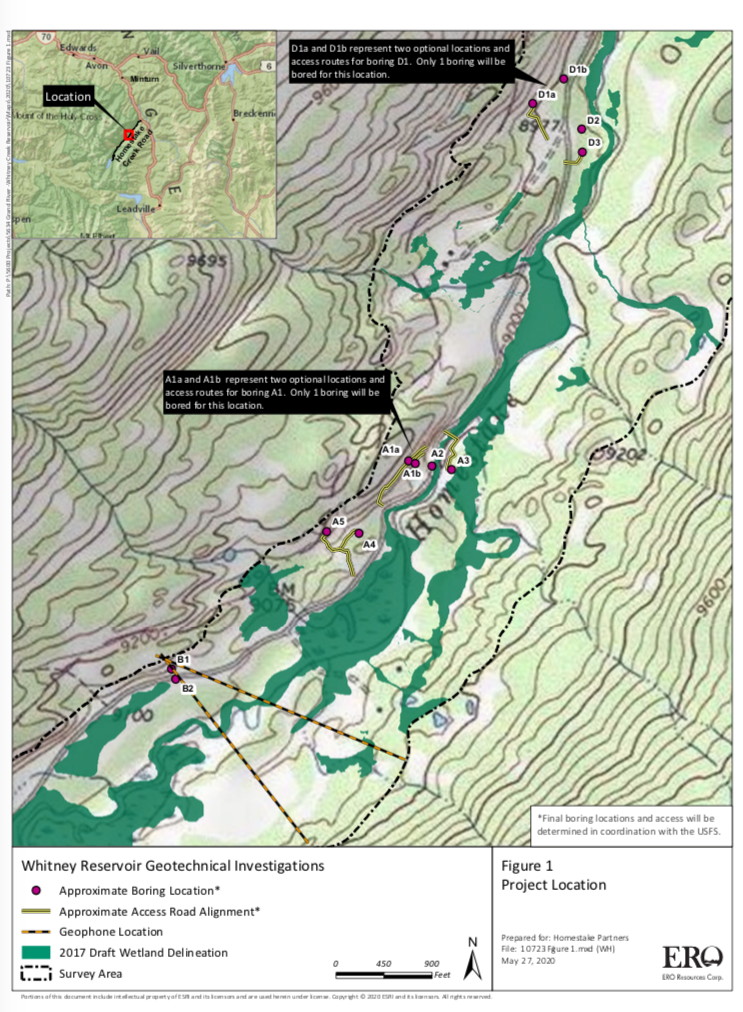

The mayors of Red Cliff and Minturn signed and submitted separate but identical letters questioning the legality of drilling 10 boreholes on Forest Service land near the Holy Cross Wilderness Area, which is six miles southwest of Red Cliff, to see whether soil and bedrock can support a dam for what would be known as Whitney Reservoir. Avon’s attorney has asked for a public comment extension to Aug. 4 so that it can hold a hearing.

“A Whitney Reservoir would irreparably change and harm our community,” Minturn Mayor John Widerman and Red Cliff Mayor Duke Gerber wrote in their letters, submitted June 30. “We are paying close attention to these proposals, other moves by Homestake Partners and the public controversy. This categorical exclusion is rushed, harmful and unlawful.”

Operating together as Homestake Partners, the cities of Aurora and Colorado Springs own water rights dating to the 1950s that, under the 1998 Eagle River Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), give them the basis to pursue developing 20,000 acre-feet of water a year from the Western Slope. They’ve been studying four potential dam sites in the Homestake Valley several miles below the cities’ existing Homestake Reservoir, which holds 43,600 acre-feet of water.

The smallest configuration of Whitney Reservoir, if deemed feasible and ultimately approved, would be 6,850 acre-feet, and the largest would be up to 20,000 acre-feet. The reservoir, on lower Homestake Creek, would pump water up to Homestake Reservoir, about five miles upstream, then through a tunnel under the Continental Divide to Turquoise Reservoir near Leadville.

In 2018, Homestake Partners paid $4.1 million for 150 acres of private land, which it leases back to the former owner for a nominal fee. That land, which would be inundated to accommodate a large portion of Whitney Reservoir’s surface area, is braided with streams and waterfalls and is lush with fens and other wetlands. It’s also home to a cabin once used as an officers quarters for the famed 10th Mountain Division of the U.S. Army. The site is not far from Camp Hale, between Red Cliff and Leadville, where soldiers trained for mountain warfare during World War II.

Eagle River MOU

The Eagle River MOU is an agreement between Aurora and Colorado Springs and a bevy of Western Slope water interests. The Colorado River Water Conservation District, Eagle River Water & Sanitation District, Upper Eagle Regional Water Authority, and Vail Resorts are collectively defined in the MOU as the Reservoir Company. None of those entities submitted comments to the Forest Service on the drilling proposal. And according to Diane Johnson, communications and public affairs manager for the ERWSD and UERWA, none are helping to pay for the feasibility study and none are involved in the reservoir project, except to the degree that it is tied to the MOU.

The MOU provides for 20,000 acre-feet of average annual yield for the cities. “Yield” refers to a reliable supply of water. In some cases, yield equates to storage in a reservoir, but yield can also be created by other methods, such as pumping water uphill from a smaller, refilled reservoir, which is an option being studied by the cities on lower Homestake Creek. The MOU also provides for 10,000 acre-feet of “firm dry year yield” for the Western Slope entities in the Reservoir Company, and firm dry year yield means a reliable supply even in a very dry year. Those entities have developed about 2,000 acre-feet of that allocated firm yield in Eagle Park Reservoir, and it’s not yet clear whether the Whitney Reservoir project would help them realize any additional yield.

“The short answer is we support (Homestake Partners’) right to pursue an application for their yield,” Johnson said. “We trust the permitting process to bring all impacts and benefits to light for the community to consider and weigh in total.” .

Jim Pokrandt, director of community affairs for the River District, declined to comment on the investigatory test work, saying only, “Yes, we have signed the MOU. That said, … we are not participating in the Whitney Creek effort.”

Besides Homestake Partners and the Reservoir Company, the MOU was signed by the Climax Molybdenum Company. The two private companies signed onto the MOU — Vail Resorts and Freeport-McMoRan (Climax) — also declined to comment on either the drilling study or Whitney Reservoir.

Under the MOU, various parties can pursue projects on their own, and the other parties are bound to support those efforts, but only to the degree that a proposed project meets the objectives of the MOU, including whether a project “minimizes environmental impacts.”

Many of the 520 online comments as of the June 30 deadline objected to testing for the possibility of a dam, expressing concern for the complex wetlands in the area, but most of the comments also strongly condemn the overall project: a potential future Whitney Reservoir.

The cities are trying to keep the focus on the test drilling.

“This is simply a fatal-flaw reservoir siting study that includes subsurface exploration, and it’s basically just to evaluate feasibility of a dam construction on lower Homestake Creek,” said Maria Pastore, Colorado Springs Utilities’ senior project manager for water resource planning. “It’s simple exploratory work to determine if we can even go ahead with permitting and design.”

Marcia Gilles, acting ranger for the Eagle-Holy Cross District, said her office will continue accepting comments at any time during the ongoing analysis of the geophysical study despite the June 30 deadline. She added that if the Forest Service concludes there are no “extraordinary circumstances,” she can render a decision using what is known as a categorical exclusion and then issue a special-use permit as soon as August. A categorical exclusion requires less environmental scrutiny than other forms of analysis.

“At this time, the proposed action appears to be categorically excluded from requiring further analysis and documentation in an environmental assessment (EA) or environmental impact statement (EIS),” Gilles said. “Should the environmental analysis find extraordinary circumstances, the Forest Service would proceed to analyzing the project in an EA or EIS.”

State Sen. Kerry Donovan, a Vail Democrat, disagrees. She wrote to the Forest Service on June 30: “I … strongly urge you not to categorically exclude this project from (National Environmental Policy Act) analysis. I cannot express how sternly the citizens of my district oppose water diversion projects to Front Range communities.” Her district encompasses seven Western Slope counties, including Eagle, where the dam would be located.

Donovan called the proposed investigation — which would require temporary roads, heavy drilling equipment, continuous high-decibel noise, driving through Homestake Creek and use of its water in the drilling process — an affront to the “Keep It Public” movement, which advocates for effective federal management on public lands.

Drilling impacts

If approved by the Forest Service for a special-use permit, Homestake Partners would send in crews on foot to collect seismic and other geophysical data later this summer or fall. Crews with heavy equipment would then drill 10 boreholes up to 150 feet deep in three possible dam locations on Forest Service land. The drilling would take place on Forest Service land but not in a wilderness area.

Crews would use a standard pickup truck, a heavy-duty pickup pulling a flatbed trailer, and a semi-truck and trailer that would remain on designated roads and parking areas, with some lane closures of Homestake Road and dispersed campsites possible.

For off-road boring operations, crews would use a rubber-tracked drill rig, a utility vehicle pulling a small trailer, and a track-mounted skid steer. The drill rigs are up to 8 feet wide, 22 feet long and 8 feet high, and can extend up to 30 feet high during drilling, possibly requiring tree removal in some areas. The rigs would also have to cross Homestake Creek and some wetland areas, although crews would use temporary ramps or wood mats to mitigate impacts.

According to a technical report filed by Homestake Partners, the subsurface work is expected to take up to five days per drilling location, or at least 50 days of daytime work only. However, continuous daytime noise from the drilling could approach 100 decibels, which is equivalent to either an outboard motor, garbage truck, jackhammer or jet flyover at 1,000 feet. If work is not done by winter, crews have up to a year to complete the project and could return in 2021.

The drilling process would use several thousand gallons of Homestake Creek water per day that engineers say “would have negligible impacts on streamflow or aquatic habitat. Water pumped from Homestake Creek during drilling would amount to less than 0.01 (cubic feet per second), a small fraction of average flows,” according to a technical report included with application materials.

Homestake Partners would avoid wetlands as much as possible during drilling, but “where temporary wetland or waters disturbance is unavoidable, applicable 404 permitting would be secured from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.” Crossing of Homestake Creek would occur in late summer or fall when streamflows are low, and no drilling would occur in wetlands.

While no permanent roads would be built for the drilling, temporary access routes would be necessary and reclaimed as much as possible.

“Access routes would be selected to reduce surface disturbance and vegetation removal, and to avoid identified or potential unexploded ordnances (UXOs) discovered during field surveys,” according to the technical report. The 10th Mountain Division used the area for winter warfare training during WWII.

Another concern cited in the report is the potential impact to Canada lynx. Listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, “only Canada lynx has potential habitat in the vicinity of the project area,” according to the report. “No impacts on lynx are anticipated from the proposed work because much of the activity would occur near Homestake Road, a well-traveled recreation access road. Work would be conducted over a short period (approximately five to six weeks) and impacts on potential habitat would be negligible.”

The vast majority of comments from a variety of environmental groups and concerned citizens focused on potential impacts to the area’s renowned wetlands and peat-forming fens, which the project proponents say they will avoid as much as possible. So far, Gilles said she is not aware of any legal challenges to the project.

Two prominent local conservation groups — Eagle Valley Land Trust and Eagle River Watershed Council — submitted comments to the Forest Service expressing serious reservations about both the drilling and the possibility of a dam.

“Geophysical exploration has an obvious significant nexus and direct relation to additional future actions, i.e., dam construction, which may in time massively impact the Eagle River watershed — regardless of whether the future actions are yet ripe for decisions,” ERWC officials wrote.

Wilderness boundary

Even if the test drilling returns favorable results for a reservoir project, there is another obstacle that Homestake Partners will have to clear if they want to move forward with two iterations of the project: a wilderness-boundary change, which would require an act of Congress and the president’s signature.

The Whitney Reservoir alternatives range from 6,850 to 20,000 acre-feet and in some configurations would require federal legislation, which the cities are working to draft, requesting a boundary adjustment for the nearby Holy Cross Wilderness Area. The largest Whitney proposal would require an 80-acre adjustment, while an alternative location, lower down Homestake Creek, would require a 497-acre adjustment.

White River National Forest Supervisor Scott Fitzwilliams discounts the notion that his agency should reject outright the test-drilling application, as some environmental groups have suggested, until the wilderness-boundary issue is determined. Although some local and state lawmakers have said they are against shifting a wilderness boundary, Fitzwilliams said it’s still too soon for him to take up the wilderness issue.

“These are test holes,” Fitzwilliams said of the drilling, which is intended to see whether the substrata are solid enough for a dam and reservoir. “Going to get a (wilderness) boundary change is not a small deal for them, so why would you do it if you find fatal flaws? That’s a red herring.

“I understand it; nobody wants to see a dam in the Homestake drainage. I get that. But it just seems prudent to do (the drilling) to see if there’s any reason to go further.”

Aspen Journalism is collaborating with the Vail Daily and other Swift Communications newspapers on coverage of water and rivers. This story was published online by the Vail Daily on July 9, 2020 and in its print edition on July 10. The early online version of the story was edited to clarify aspects of the Eagle River MOU.

This story was published by Aspen Journalism on July 10, 2020.

This story was supported by The Water Desk using funding from the Walton Family Foundation.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism. The Water Desk is seeking additional funding to build and sustain the initiative. Click here to donate.