An ambitious plan would use carbon credits as incentives to convert Delta islands to wetlands or rice to halt subsidence and potentially raise island elevations

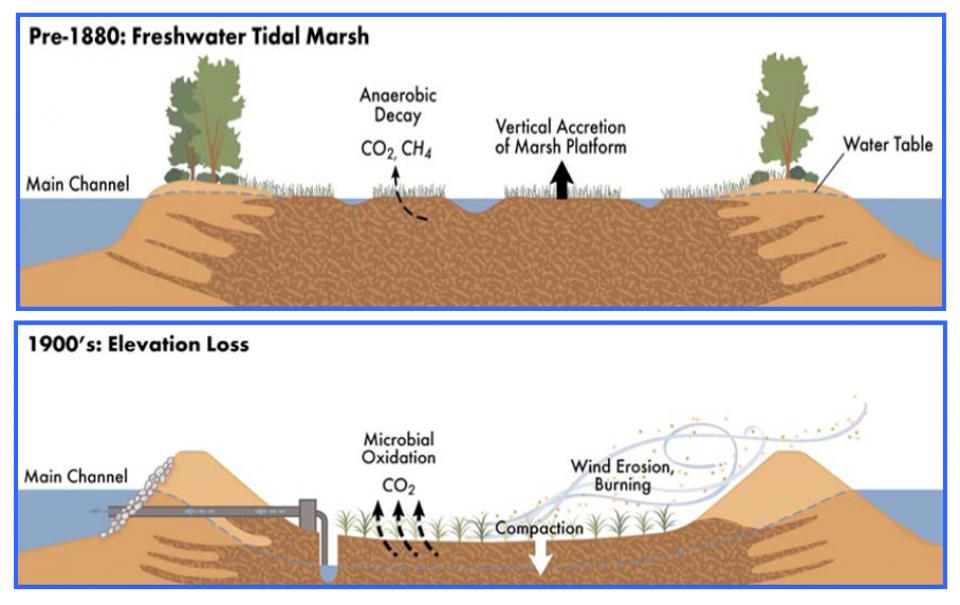

The islands of the western Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta are sinking as the rich peat soil that attracted generations of farmers dries out and decays. As the peat decomposes, it releases tons of carbon dioxide – a greenhouse gas – into the atmosphere. As the islands sink, the levees that protect them are at increasing risk of failure, which could imperil California’s vital water conveyance system.

An ambitious plan now in the works could halt the decay, sequester the carbon and potentially reverse the sinking.

The plan would provide a carrot for farmers in the western Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to convert their island acreage to rice fields or managed wetlands in order to cut carbon emissions from the decaying peat and protect their lands and communities as well as California’s water hub. The Delta is the “switching yard” for moving water to the massive pumps for the State Water Project and federal Central Valley Project.

Shepherded by the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Conservancy, the Delta Carbon Program is near completion of the first-ever third-party verification of wetlands that quantifies the carbon emission reduction estimates from 1,600 acres of managed wetlands on Sherman and Twitchell islands operated by the California Department of Water Resources.

The aim is to use that example to encourage Delta landowners to ultimately access the state’s cap and trade market for carbon credits. About 2 million metric tons of carbon are emitted annually from the entire Delta, the equivalent of about 500,000 motor vehicle emissions.

Campbell Ingram, executive director of the Delta Conservancy, the state agency charged with fostering actions to support the Delta’s ecosystem and economy, said the land conversion idea targets about 200,000 acres of islands in the western Delta that are the most subsided and of marginal value. That amounts to more than a quarter of the Delta. About 50,000 acres of this region are under public ownership, providing an opportunity to demonstrate the viability of carbon farming to surrounding landowners.

“It’s a unique little patch of land, the subsidence of which really threatens California’s water supply,” he said. “Also, it’s a chimney that’s just rocketing carbon into the atmosphere.”

Delta islands are seen increasingly at risk of flooding and levee failures from subsidence and sea level rise due to climate change, which could pull salty water deeper into the Delta and foul exported water.

“If you can convert these soils to anaerobic conditions, you reduce the carbon emissions and you have a tendency to stop or slow way down the subsidence factor.”

~Tom Zuckerman, Delta farmer

The answer to reversing subsidence and carbon emissions lies in reverting that part of the Delta to its former marshy legacy. Instead of cultivating crops that dry the soil and exacerbate the problem, the idea is to keep the land perpetually wet, even during the hot summer months. That can be done through converting land to rice or managed wetlands. Either way, it will be a transition for Delta agriculture, Ingram said.

“With managed wetlands, you get more carbon revenue and more accretion, but it does take ag land out of production, which is not a comfortable space,” he said. “On the other hand, if the agricultural practice continues to increase the risk of levee failure, continues the huge carbon emissions and it’s not economically viable … it makes it a tough argument for people to say you’ve got to stop taking ag land out of production.”

Launching pilot projects that demonstrate the potential of reducing carbon emissions from land alterations is challenging because landowners are reluctant to pay the upfront costs when the expected revenue isn’t known, Ingram said,

Tom Zuckerman, a Delta farmer who has been working with the Delta Carbon Program on getting more rice into production, said he has seen a growth in rice production and that the benefits are evident. According to the Delta Protection Commission, Delta rice production increased by about 53 percent, from 4,874 acres in 2009 to 7,468 acres in 2016.

“It’s a double-winner situation,” Zuckerman said. “If you can convert these soils to anaerobic conditions, you reduce the carbon emissions and you have a tendency to stop or slow way down the subsidence factor.”

Zuckerman, who co-owns 1,000 acres, said he is planning to convert a portion of that acreage to rice and has heard the same from other farmers. Rice, he said, is a profitable commodity though upfront work is needed.

“The barrier is that land has to be worked on quite a bit for leveling and re-ditching so there is a capital barrier to entry on the conversion,” he said. “Once that happens, every indication is that farmers will be better off with the rice crop, both from what they get from the crop plus what they might get from carbon credits.”

A viable option

The Delta’s rich, organic peat soil is wonderful for farming, but decades of cultivation have altered the natural hydrology. The peat soil is fragile and susceptible to subsidence. Decades of farming have carved out large bowls in the Delta, some of which are 25 feet below the adjacent river channels.

Crops such as corn and alfalfa require a drained root zone that exposes the peat soil to oxygen and breakdown and releases stored carbon into the atmosphere.

The Delta’s peat slows seepage from the surrounding rivers that are perched 20 to 30 feet above the land surface. When the peat gets thin, water seeps through the underlying sand, leaving areas too wet to farm. Ingram pointed to a recent study showing that in the 1980s about 500 acres were too wet to farm; now that’s about 5,000 acres.

More than 20 years ago DWR began research at Twitchell Island, near the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, on how to stop subsidence. By altering the landscape and getting water back on the land, they created a tule marsh that halted subsidence and slowly rebuilt surface elevation. In the process, the state realized a carbon benefit from stopping the breakdown of the peat soils. That has become the test bed for the carbon capture protocol.

Each acre converted to marsh keeps from six to more than 20 metric tons of carbon emissions out of the atmosphere each year. Quantifying those reductions and the associated carbon credits is the key.

The first third-party verification of carbon reduction credits is expected to be completed anytime now. The final product, Ingram said, will go to the American Carbon Registry, a private, voluntary greenhouse gas registry that validates the environmental and scientific integrity of carbon offsets, where credits can be sold to realize a revenue stream.

Ultimately, the aim is for the California Air Resources Board to adopt the Delta Conservancy’s protocol into its compliance program under AB 32, the state’s landmark 2006 greenhouse gas law. Adoption is expected to raise the value of carbon emission reduction credits to as much as $180 per acre.

Each acre converted to marsh keeps from six to more than 20 metric tons of carbon emissions out of the atmosphere each year.

~Delta Conservancy

“Our expectation is that the incentive will continue to grow and can compete with the current commodities that are grown in the Delta and be a real viable option for landowners, public and private,” Ingram said.

Chris Scheuring, managing counsel with the California Farm Bureau Federation, said the Farm Bureau isn’t opposed to voluntary transactions that convert Delta farmland to other uses, but worries about the loss of good soil for farming and the impact on farmers. Ultimately, he said, it’s up to individual landowners to decide whether participating in the cap and trade carbon market makes sense for them.

“The compensation has to be there,” Scheuring said, “and it’s got to make economic sense to the farmer.”

Michelle Passero, director of The Nature Conservancy’s California Climate Program, said marketing Delta carbon aligns well with her organization’s mission of keeping the region a haven for birds.

“We are interested in exploring different practices that can help address climate change while also maintaining habitat for cranes,” she said.

Building a market for carbon credits

The Delta is an agricultural powerhouse, growing whatever commodities the market demands – corn, alfalfa, tomatoes, rice, grapes and orchard crops. However, there is concern that factors external and internal could create a quandary for future land management.

At the Delta Stewardship Council’s November meeting, Delta Watermaster Michael George expressed concern about what could happen to areas that are no longer a good investment for agriculture.

“There is a substantial risk that some of those areas [that] will not be able to be farmed profitably may be abandoned” and end up in the state’s lap, he said.

If land does default to the state, it will have to be managed, perhaps for wetlands or rice and reaping carbon benefits. AB 32 requires California to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by this year. Carbon offsets allow businesses to fund projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as the kind advocated by the Delta Conservancy.

In January, the state’s draft Water Resilience Portfolio said among its aims is to provide incentives and technical advice to Delta landowners for creating managed wetlands or cultivating rice and to “eliminate subsidence-inducing practices on state-owned lands and pursue alternative sources of revenue to support long-term land management.”

The current voluntary market for carbon emission reduction credits is about $60 per acre annually. That figure exceeds most annual per-acre leases in the deeply subsided western Delta, Ingram said, but does not fully compete with commodity prices. Furthermore, there are costs associated with converting land to managed wetlands or rice.

“It’s really hard to get farmers to say, ‘I am going to pay those upfront costs and then make less money than I make now,’” Ingram said.

Erik Vink, executive director of the Delta Protection Commission, said it’s important to prove the concept of carbon emission reduction credits in a way that sends the right economic signal to landowners.

“If you want them to farm tules, they’ll be the best tule farmers you’ve ever seen,” he told the Delta Stewardship Council in November.

A carbon credit value of between $15 and $20 per metric ton would help the economics of farming rice, said Zuckerman, the Delta farmer, adding that depending on the circumstances, revenue from carbon credits could begin look like “serious money.”

About 50,000 acres in the western Delta are publicly owned or publicly financed, raising the question of whether marketing carbon credits is a viable alternative for public agencies that need a reliable revenue stream for operations and maintenance.

Ingram said he believes once the program gets rolling, landowners — including public agencies — will see the benefit. And with a carbon credit market providing incentives to convert land to wetlands or rice, Ingram said the potential exists for increasing land elevation to help levee stability under an aggressive approach that could yield results in as few as 40 years.

While a key goal is to reduce carbon emissions, he said, the larger objectives are to stop land subsidence that ”continues to threaten the economic vitality of the region” and poses a “huge risk” to the state’s water supply.

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @GaryPitzer

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story originally appeared on Western Water on Feb. 27, 2020 and is republished here by permission.