A proposed hydroelectric project on the Little Colorado River shows the tricky trade-offs in transitioning from fossil fuels.

By Nick Bowlin, High Country News

Just outside Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona, a year-round, mineral-rich spring turns the Little Colorado River a vivid turquoise. This final stretch, about 10 miles from the river’s confluence with its larger relative, is one of the West’s spectacular waterways, with bright water flowing below steep red-rock cliffs. But the view will change dramatically if a Phoenix-based company builds a proposed hydropower project. The two dams could alter the flow, discolor the water and flood a Hopi cultural site.

The project remains a long shot: It needs the approval of the Navajo Nation, whose leaders have been publicly skeptical. It also has to contend with varying river flows and the protected humpback chub, plus a remote location that will require building extensive transmission lines. The river’s beauty makes this particular project stand out, but it’s just one of a number of proposed hydropower projects around the West.

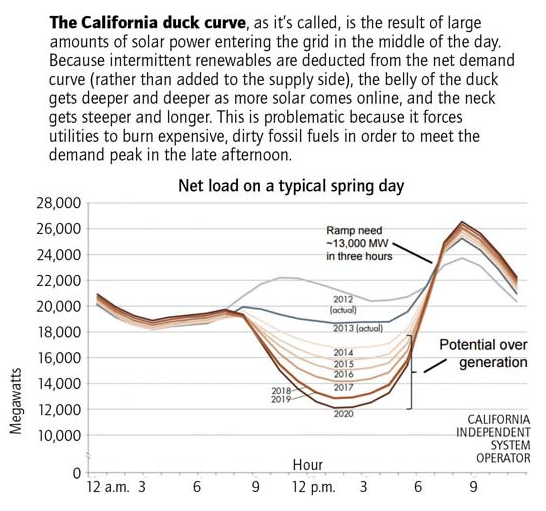

The structure of today’s energy market helps explain hydropower’s appeal, even for dubious projects like this one. As it stands, renewables struggle to match power supply to common patterns of demand (as revealed by solar energy’s “duck curve”). The result is a renewable energy bottleneck. If the U.S. is to meet global climate goals, an enormous, rapid shift away from fossil fuels is needed. This creates what one recent academic paper calls “green vs. green trade-offs,” exemplified in the West by the recent trend of proposed hydropower dams. Such projects destroy waterways and harm ecosystems — but they could also help purge the grid of fossil fuels.

Solar power works only during the day, and wind is inconsistent. To meet peak power demand, which tends to spike at night, utilities rely on coal, nuclear and — increasingly — natural gas. In order to rapidly increase and decrease supply to meet real-time demand, gas plants must run all the time. This limits the amount of solar and wind power the grid can accommodate, thereby prolonging fossil fuel use. States are already producing more solar and wind power than their grids can take.

The capacity to store the day’s excess solar and wind power for nightly use would solve the problem. Battery storage, while advancing fast, is years away from being both advanced enough to replace gas plants and fully integrated into power production, according to Suzanne Stradling, a University of New Mexico Ph.D. student who is studying the renewable transition. If we could meet peak power without natural gas, she said, “there’s no limit to the amount of solar we could bring onto the grid.”

But how do you manage without gas power? Coal is a greater pollutant, and nuclear waste is politically — as well as environmentally — toxic. That leaves hydropower. Like gas, hydropower can ramp up power generation almost instantly. Pumped storage dams, which are essentially enormous batteries, could meet peak power demand, allowing solar and wind energy to chase gas and coal from the grid. Fourteen of the 15 dams proposed in the West this year are designed for pumped storage, according to federal data. But many face obstacles similar to those confronting the Little Colorado project.

Some proposed Western dams would use existing infrastructure, not natural systems like the Little Colorado River. There is a move to transform an abandoned iron mine outside Joshua Tree National Park into a massive hydropower plant, for example, while Los Angeles wants to convert Hoover Dam into a pumped storage facility. But by the time new projects are permitted and built, “things in the energy industry are going to look entirely different,” Stradling said. This uncertainty can make it hard to attract investors. And in another region-wide trend, several multi-state transmission projects — the kind that will bring Wyoming’s excess wind power to other states — are already underway. Recent expansions to California’s energy imbalance market are another important step toward a true regional market. A more unified grid, combined with better battery storage, will reduce the need for hydropower projects.

Meanwhile, other hydropower projects are coming online. A $1 billion pumped storage dam will begin construction in Montana next year, and another hydropower project has been approved in California’s San Diego County. Both are near transmission lines and will help decarbonize Western grids.

But what sort of future are we committing ourselves to by building these dams? This question occupies University of Wyoming professor Tara Righetti. The infrastructure we build now, she said, will lock us into certain futures, while denying others. The enduring difficulty of accounting for 20th century infrastructure is apparent in behemoths like Glen Canyon Dam and the push for dam removal on the Snake River in southeastern Washington. Even after battery technology improves and the power grid supplies Nevada with Wyoming wind on a cloudy day, hydro storage dams will still exist. For there is a cost to not building them — our continued reliance on existing energy infrastructure and natural gas plants to keep the lights turned on.

“All power sources have an impact,” she said. “If there’s a human imperative to address climate change, that means finding the right spot to make these trade-offs.”

Nick Bowlin is an editorial fellow at High Country News. Email him at nickbowlin@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor.

This story was originally published at High Country News on Nov. 1, 2019.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism. The Water Desk is seeking additional funding to build and sustain the initiative. Click here to donate.