ASPEN — Approaching Labor Day weekend of 1961, many Aspenites who had plans to go camping or enjoy outdoor concerts watched in trepidation as monsoon rains didn’t let up for two days. Then, that Friday night, the damp chill turned rain to snow — large, wet snowflakes fell overnight and for the next two days, thoroughly coating the green, late-summer landscape. Tree limbs bent and snapped, the music tent started to rip under the weight of the snow, motorists were stranded when Independence Pass closed and the power went out in the city for two days.

“It was a hell of a mess,” said lifelong Aspenite Jim Markalunas.

The mayor called Markalunas and asked him to reboot the defunct hydroelectric plant he had previously run while the regional electric utility struggled to restore the downed lines.

He managed to restore power to Aspen, and by the time residents woke up to a cold, sunny Labor Day morning, 27 inches of snow had fallen in town, a record that still stands, according to Markalunas, author of “An Aspen Weather Guide” and “Aspen Memories.”

Now 89, Markalunas also has tales of being surrounded by massive snowbanks as a 6-year-old in the 1930s and worrying about roofs collapsing from the heavy-snow years of the 1980s.

“Big snow years are oh-be-joyful for the (Aspen Skiing Company) and skiers but made for a lot of hard work for people maintaining the streets and intakes and such,” he recalled.

Markalunas remembers lean years, too, most notably the winter of 1976-77. That ski season didn’t start until January and recorded just 86 inches of snow all winter. It also spurred massive investments in technologies to battle drought impacts, such as snowmaking and cloud-seeding.

Markalunas likes to say that Aspen’s weather is “consistently inconsistent.” But he started noticing a difference in patterns in the 1980s — in particular, less-frequent below-zero temperatures.

“The trend is we just don’t have the super-cold weather we used to have,” he said, pointing to weather data he has compiled from water department records showing that Aspen has hit a low of less than minus 20 just once since 1997.

“It seems as though the weather pendulum swings more extremely than in years of old,” Markalunas writes in “An Aspen Weather Guide.” “Storms are more violent but less frequent. The weather appears to be more volatile than in past years. … Unless we act to decrease carbon dioxide emissions, ski racks on SUVs might become useless accessories here.”

Markalunas’ observations are supported by other data, analyses and studies that paint a picture of a changing local climate. Pitkin County is warming, the number of frost-free days is increasing and snowpack is declining — all of which have myriad impacts on recreation, the ecosystem, wildlife, streamflow, water availability, droughts and wildfires. One of the most notable impacts is on the underpinning of modern Aspen’s economy: snow and skiing.

Officials at Aspen Skiing Company, or SkiCo, have been aware of changing temperatures and snowfall for some time. Like others, the biggest change that Rich Burkley, SkiCo’s senior vice president of strategy and business development, has seen in his 30-year career is more variability.

“It’s a feast of riches or famine, and you have to deal with that,” he said.

The start of this ski season has been a feast, with above average snowpack across the state.

It’s getting warmer

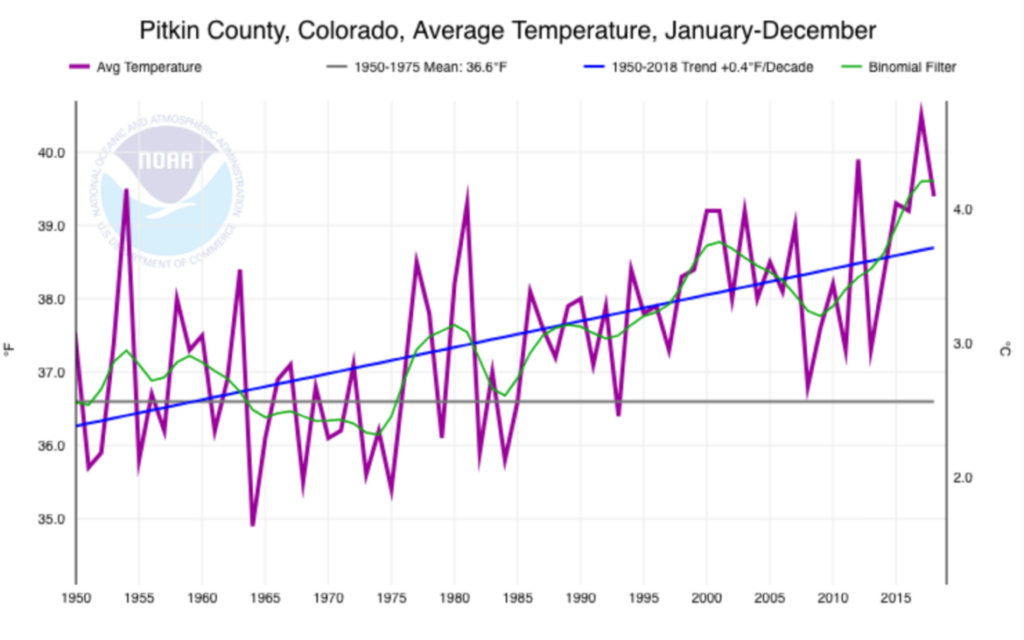

Pitkin County’s average temperature has been rising at a rate of 0.4 degrees per decade since 1950, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In 2018, the average temperature throughout the year in Pitkin County was 39.5 degrees — 2.9 degrees warmer than the mean temperature during the baseline period of 1950-75.

Pitkin County’s average temperature each year since 1950 has risen, at a rate of .4 degrees Fahrenheit per decade, compared to the mean (gray line) temperature during the 1950-1975 baseline period. The Climate at a Glance tool, from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, can be used to plot historical temperature or precipitation data in a time series from a global to a city level.

More-dramatic changes are happening in the cold-season months. Temperatures are rising almost half a degree per decade between November and April, compared with about one-quarter of a degree the other half of the year.

March is by far the fastest-warming month, heating up at a rate of 1 degree per decade since the 1950s. The average temperature of 34.4 degrees in March 2017, when Aspen hosted the World Cup ski racing finals, was a record 9.4 degrees higher than the 1950-75 baseline temperature.

The race venue on the lower half of the mountain lost several inches of snow surface per day, Burkley said. The only reason there was enough snow to race on was extra early-season snowmaking that at the time was considered excessive.

Markalunas’ theory of fewer really cold days shows in this data as well. Average annual low temperatures have risen in Pitkin County and appear to be accelerating — average minimum temperatures were more than 5 degrees higher than the baseline during three of the past five winters.

Low temperatures in the winter months in Pitkin County are rising faster than average yearly temperature — at a rate of .5 degrees per decade. The average low from November through April was 12.4 degrees from 1950-1975; it reached a record high of 18.1 degrees in the winter of 2016-17.

“Even since 1980, there has been a pretty sharp annual average temperature increase over time,” said Elise Osenga, research and education coordinator for the nonprofit Aspen Global Change Institute, or AGCI. “Even just a couple degrees difference is a notable difference in annual average temperatures — especially if you are a seasonal-sensitive plant or animal.”

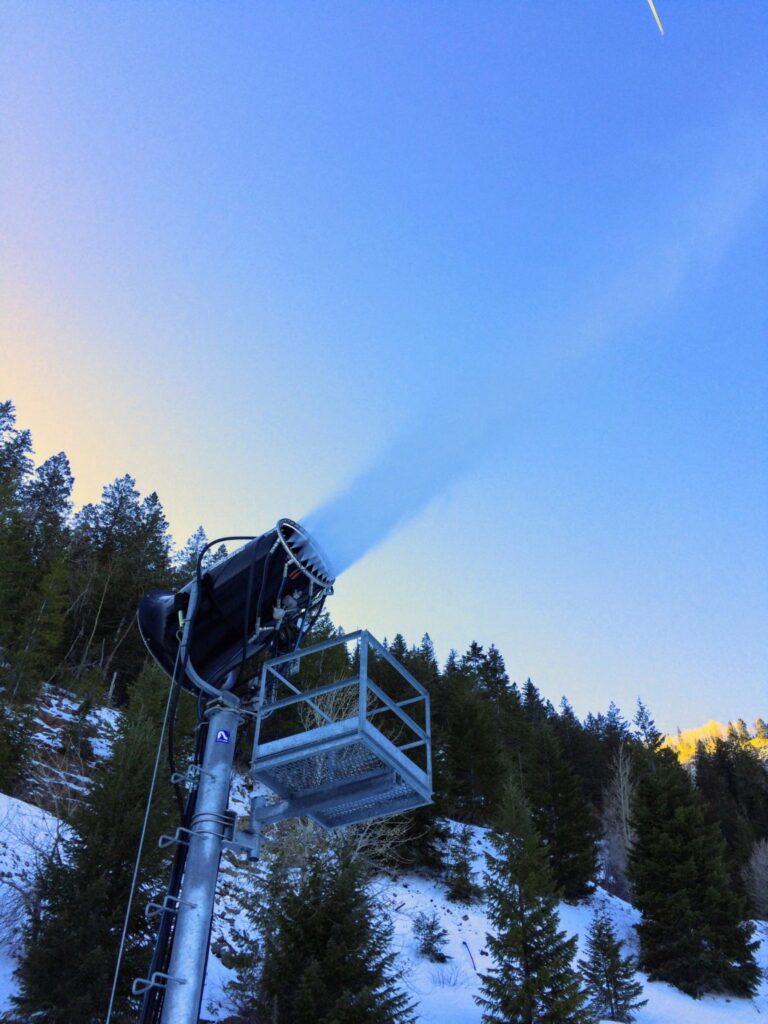

A 2014 report by AGCI notes that rising low temperatures, particularly in early winter, can affect the ability to make snow on the ski mountains, an activity typically limited to November and December. This hasn’t impacted SkiCo much yet, according to Burkley. Snowmaking now is about twice as efficient as it was two decades ago, thanks to automation and improved technology.

SkiCo also has plans to expand snowmaking to the top of Aspen Mountain next season, which Burkley said will be key to Thanksgiving openings as the upper part of the mountain often doesn’t have enough natural snow in November.

Zooming out, a recent Washington Post feature found that Pitkin County and much of the Colorado Rockies are warming faster than other places. Pitkin County’s average temperatures have risen 2.34 degrees since 1895, at the height of the Industrial Revolution; the average across the United States is 1.8 degrees. In fact, western Colorado and eastern Utah comprise a large “hot spot” that warns of greater climate shifts to come.

Freezing? Not so much

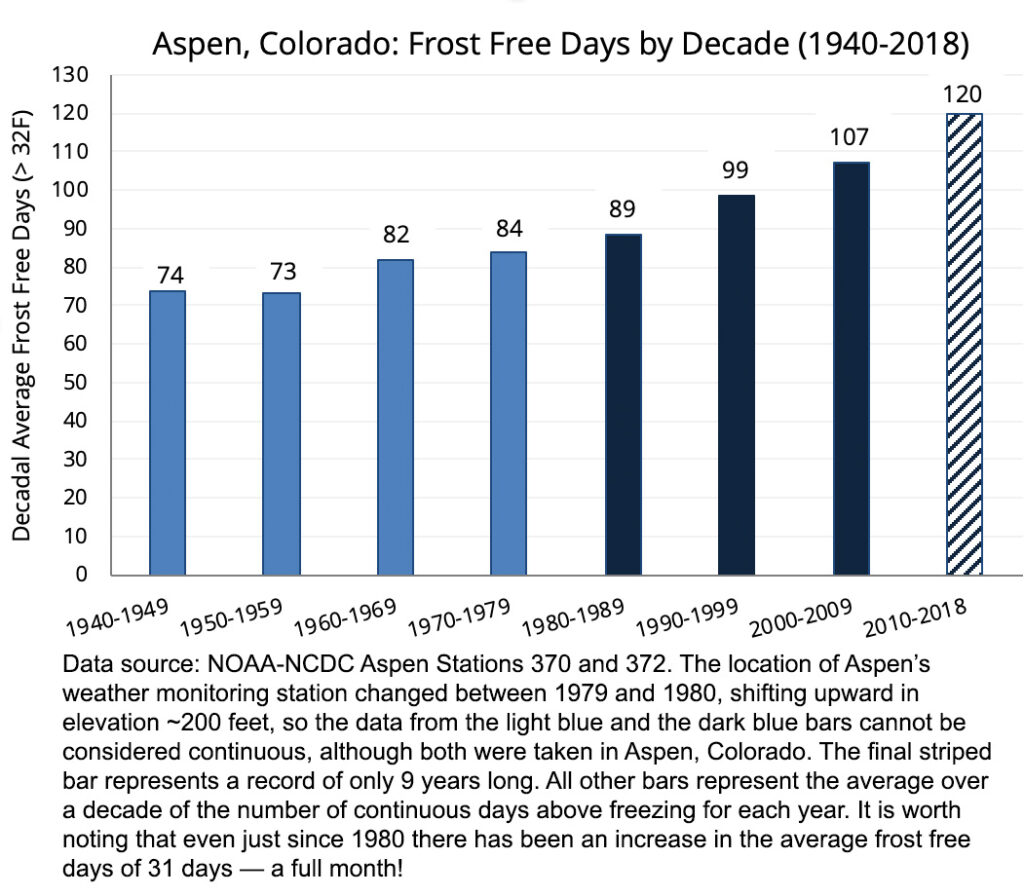

One critical trend related to rising temperatures — in particular, rising low temperatures — is an increase in the number of frost-free days, which AGCI counts as consecutive days of above-freezing temperatures from the last freeze of spring to the first time it dips below 32 degrees after that. Like temperature, the number of frost-free days has risen sharply in recent decades.

Since the 1980s, there’s now an additional month each year without freezing temperatures in Aspen, according to AGCI’s analysis. The actual number of days above freezing varies widely from year to year, but there is a clear upward trajectory, as seen in the Forest Health Index, which is produced by the Aspen Center for Environmental Studies with help from AGCI.

“When it’s not freezing, there won’t be snow to accumulate,” said AGCI executive director John Katzenberger. “And those adaptations like making snow will be more important but will be more curtailed by when temperatures are sufficiently cold to make the snow.”

A shorter freezing season could also reduce snowpack if more precipitation comes as rain instead of snow and shorten the end of the ski season if snow melts faster and earlier.

“(Climate change is) impacting us, but so far we’ve been able to adapt,” said Burkley. “There’s a lot of long-term capital planning, though: expanding snowmaking, higher snowmaking, water storage, and possibly adjusting operational times and dates.”

Higher temperatures mean less snow

Changes are, of course, also being felt beyond ski-area boundaries. In the summer of 1994, big-mountain skier Chris Davenport first skied 14,092-foot Snowmass Mountain, named for the massive snowfield that historically stretched across a wide bowl below its summit.

“In the next decade or so, it seemed like that permanent summer snow was getting smaller and smaller, until one summer in the mid-2000s, it was totally gone,” said Davenport. “It’s a direct effect of warming — even if it’s a few degrees, that snowfield couldn’t hang on.”

Winter snow might still linger into the summer months on Snowmass, Davenport said, but most years, the formerly year-round snowfield is gone by mid-July.

A skier hikes toward the 12,392-foot summit of Aspen Highlands in December 2017, during a low-snow winter. The ridge leading to Highland Bowl is usually covered with snow, even early in the winter.

The waning snowfield on Snowmass Mountain is representative of a larger trend. Summer snow covering the Northern Hemisphere receded from 10.28 million square miles at its peak in 1979 to a low of 3.69 million miles in 2013, according to Climate Central’s website WXshift.com. Not only does that impact water supplies, but less snow cover means more sunlight absorbed by Earth, driving a feedback loop of further temperature increases.

Snowfall has also decreased in many parts of the United States, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, although no significant trends in precipitation have been found in the Aspen area or Colorado in general. Some climate models predict more precipitation in the future, but rising temperatures could mean that precipitation comes more often as rain rather than snow.

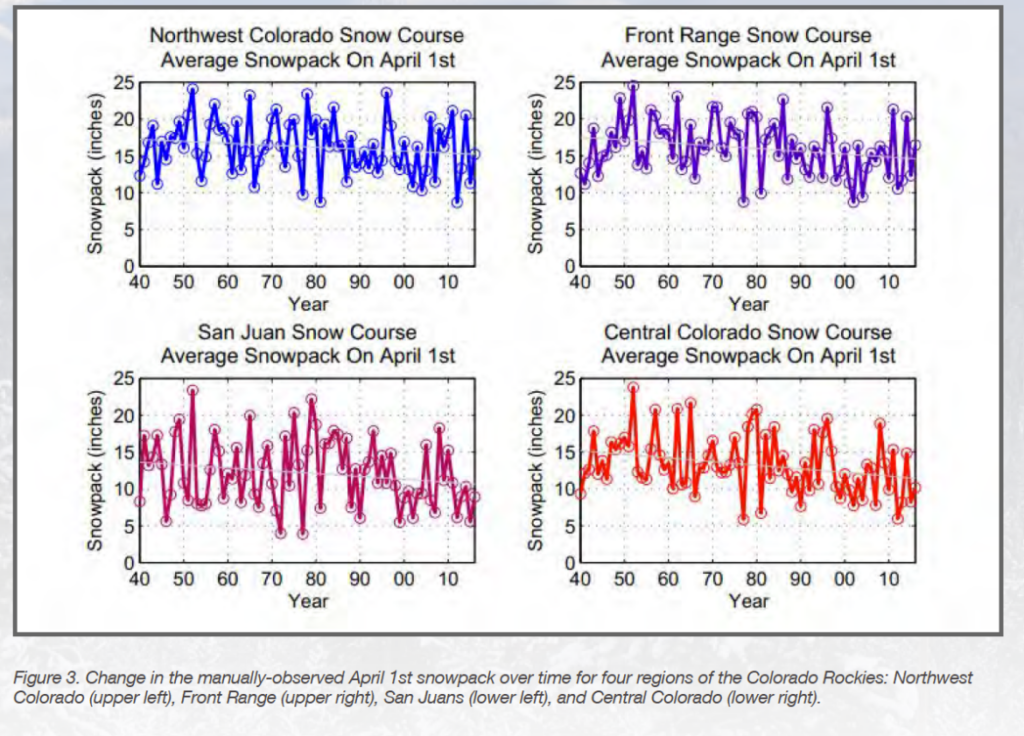

In Pitkin County, as in the American West and other mountain drainages around the world, snowpack is arguably the most consequential climate-change indicator. Mountain snowpack not only determines availability of snow for recreation but also how much water will be available for all manner of natural and human uses. In Colorado, including the Roaring Fork River valley, snowpack — usually measured by the amount of water in the snow, known as snow water equivalent, or SWE — is generally variable and can range widely from year to year. But this, too, has become more extreme in recent years.

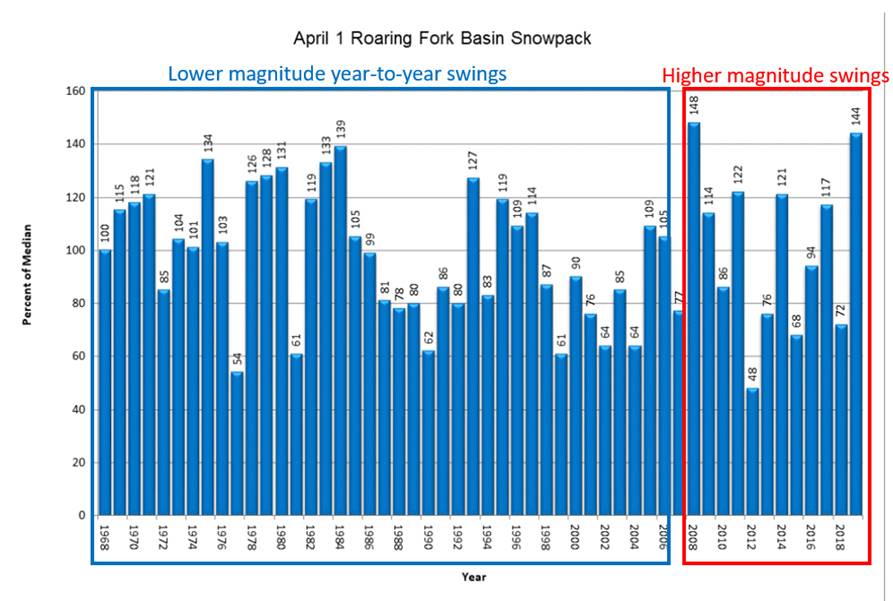

“We’ve observed these huge year-to-year shifts,” said Karl Wetlaufer, a hydrologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Colorado Snow Survey, which collects and manages snowpack data. “So that does feel like a trend: Over the last 15 years, things seem to be much more erratic, with more extreme years on both high and low ends.”

The scientific community considers the April 1 snowpack the peak of the water year. Only once since 2010 has the Roaring Fork basin’s snowpack on April 1 been measured between 85% and 115% of normal, said Wetlaufer. That range was more common in earlier periods.

Hydrologist Karl Wetlaufer noted recent large swings in Roaring Fork basin snowpack data from the USDA’s National Water & Climate Center. The past 10 years show higher peaks and valleys than the longer-term record.

The last two winters feature some of the wildest snowpack swings — and the most extreme weather events. From October 2017 to September 2018, snowpack peaked at 72% of normal; the following snow season, it peaked at 144%.

The low-snow season resulted in such tinder-dry conditions that the Lake Christine fire, the most threatening fire in recent valley history, burned for months in the summer of 2018. That was followed by a winter capped off with an unprecedented avalanche cycle, the result of a steady buildup of the snowpack on a weak base layer, ultimately unleashed by a massive storm cycle that was fueled by warm atmospheric rivers from the Pacific Ocean.

Besides more variability, some recent scientific analyses, including this map produced by the EPA and AGCI’s 2014 report, have found that Colorado’s snowpack is decreasing. A study published by Peter Goble and Nolan Doesken of Colorado State University’s Colorado Climate Center found that central Colorado’s snowpack is diminishing by an average of .49 inches of SWE per decade, which was the most of the four regions studied. This calculation includes measurements taken at a station near Independence Pass.

A half-inch of SWE can equate to 7.5 to 10 inches of snowfall, Goble said, which over 100 years could mean 75 to 100 fewer inches of snow — about one-third of the roughly 300 inches that fall on average on the Aspen Snowmass slopes.

“Considering that loss may accelerate, those numbers look a little threatening to the local lifestyle,” said Goble.

Recent research also accounts for factors such as dust on snow, likely to be more frequent in the future given the increasing aridity of areas west of Colorado and more human disruption of those areas. Dust on snow, similar to rain on snow, melts the snowpack more quickly.

Scientists agree that the main factor contributing to a declining snowpack is not less snowfall but warmer temperatures due to increased greenhouse-gas emissions. And because temperatures are expected to continue to rise — the amount depends on how much emissions are curbed — snowpack around Aspen and elsewhere will continue to decline.

Still, Goble is hopeful.

“When you look at the projections and how winters might change, it’s not a totally hopeless situation,” he said. “We still have control over our future. If this is a problem humans take seriously and we see a lot of action on a large scale over the next couple decades, it will make the outlook for the back half of the century a lot brighter than if it was business as usual.”

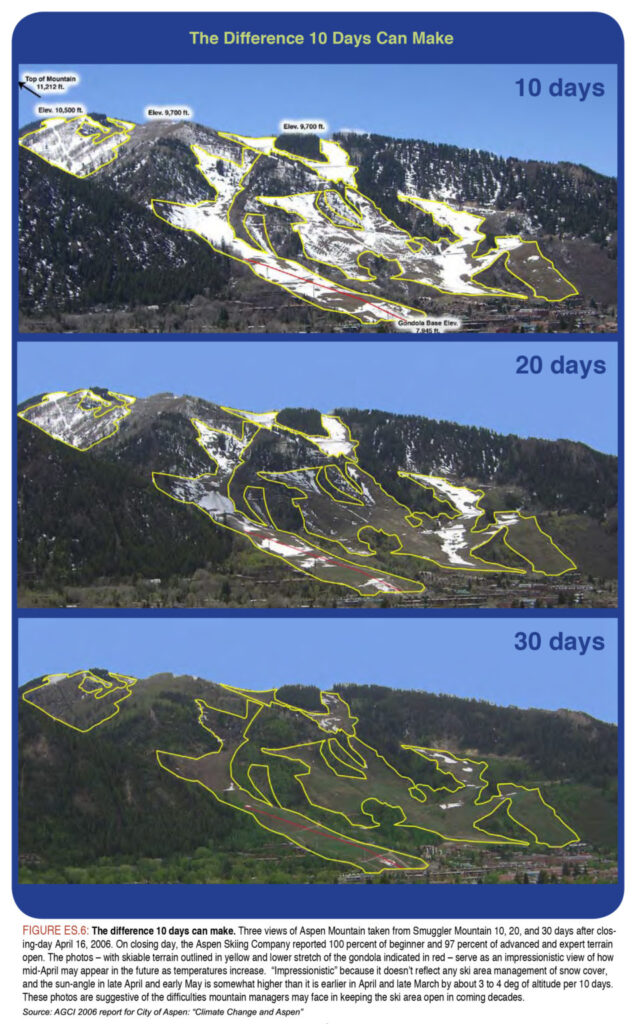

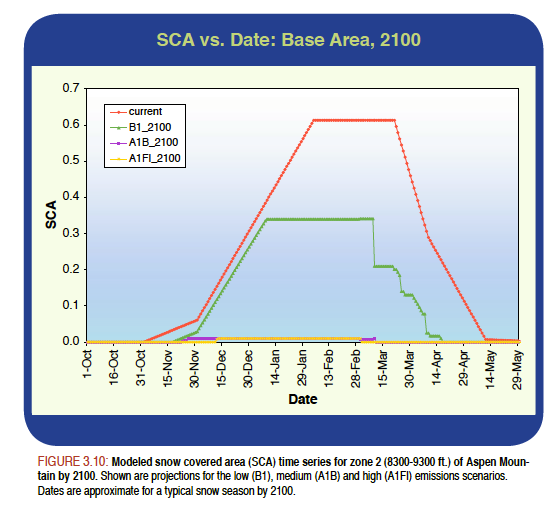

AGCI’s 2006 report for the city of Aspen, on the other hand, painted a dire scenario for future skiers (as well as downstream water users) with continued warming, including the potential for shorter ski seasons and substantially reduced snow cover.

Aspen Mountain will still be skiable in 2030 under all emissions scenarios, the report concluded, but “by 2100 the base area of Aspen Mountain has essentially lost a skiable snowpack, with the exception of the lowest greenhouse-gas concentrations.”

In all future emissions scenarios, the AGCI report found that Aspen Mountain’s base snowpack will start to accumulate later in the fall and melt earlier in the spring due to warming temperatures. Snow depths at all elevations are projected to be reduced throughout the season. In the worst-case scenario, the ski season will be 10 weeks shorter by 2100 and “snow depth goes to near zero for the entire lower two-thirds of the mountain.” That’s everything below the base of the Ajax Express chair.

“Under these scenarios, some of our seasons are shortened and our terrain could be reduced,” Burkley said. “We would be in download situations more frequently. We would build and concentrate snowmaking at higher elevations. We might have more hike-to or hike-out terrain. We would build lifts to access areas that have more consistent snowpack.”

Burkley said with existing infrastructure, SkiCo can offer lift-served, high-elevation skiing on three mountains. The proposed 180-acre Pandora expansion on top of Aspen Mountain also would expand into terrain that “will probably have the best snow in the future.”

A machine blows artificial snow at the top of Little Nell on Aspen Mountain in Dec. 2017. SkiCo is building out snowmaking infrastructure as one way to adapt to a changing climate, but that, too, relies on sufficient water in local streams and cold enough temperatures.

Even as SkiCo relies more on snowmaking, Burkley acknowledges minimum streamflow requirements could be an additional challenge. There could be a time when natural snowpack declines to the point that there won’t be enough water in local streams to make all the snow it needs, in which case the company might have to decide to shut down one or more of its four mountains and focus efforts on what remains open.

SkiCo is also increasing its focus on summer operations, including Snowmass Bike Park. For now, this helps ensure a return on expensive infrastructure; later, it could help make up for shorter winters.

Ironically, the Aspen Snowmass ski areas could actually benefit in the short term from climate change. They’re situated at higher elevations with colder temperatures than many other resorts, especially those outside of Colorado, and could see increased visitation as lower-elevation ski areas become less viable.

Clearly, Aspen isn’t the only ski resort facing an existential crisis. Ski areas across the country are recognizing the challenges that climate change poses to their viability, and that’s provoking a shift in industry thinking.

“In recent memory, climate was an uncomfortable conversation. Resorts said it was politicized science,” said big-mountain skier Davenport, who is now a climate activist and board member of the advocacy group Protect Our Winters, or POW. “Now everyone’s on board.”

The scale of action is bigger than resorts switching to renewable energy or lobbying for climate-friendly policies in Washington, D.C., as SkiCo has been doing for years. Three of the largest industry groups — Outdoor Industry Association, Snowsports Industries America and National Ski Areas Association — recently formed the Outdoor Business Climate Partnership to provide leadership and inspire action on climate change. Using POW’s playbook, SIA launched United by Winter, a climate-advocacy platform for its members. And POW is now on the radar of elected officials in every state where the outdoor industry has a presence.

“It used to be inconvenient for outdoor companies to talk about climate change, but now the opposite is true: If you’re not having that conversation, consumers aren’t buying from you,” Davenport said. “Look how we’ve changed the conversation.”

This story was originally published by Aspen Journalism on December 18, 2019.

Editor’s note: Aspen Journalism is collaborating with Aspen Public Radio on coverage of environmental issues. A conversation about this story aired on Dec. 19.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism. The Water Desk is seeking additional funding to build and sustain the initiative. Click here to donate.