By Jason Plautz

Even before COVID-19 swept across Colorado and other states, concern over the cost of water had begun to rise.

Nearly 12 percent of American households lack access to affordable water, a number that is expected to triple in the next five years, according to a 2018 study from Michigan State University (MSU).

The good news: Western states are still able to provide relatively affordable water, but that could change as utilities try to recoup losses associated with the pandemic and begin to pay for the massive repairs and upgrades to their systems that were on the drawing board before COVID-19 struck.

Measuring affordability

In Colorado, newer infrastructure and conscious rate-setting has kept water largely affordable, as in most Western states. The MSU study found that less than 8 percent of Colorado’s census tracts were at “high risk” of an affordability crisis based on income, better than all but 12 other states. (“High risk” tracts were defined with a median income of less than $32,000, where rate increases would disproportionately affect ratepayers’ budgets.) Among the regions identified in the study as at risk were Denver, Pueblo, Colorado Springs, and Alamosa in the San Luis Valley.

Water systems built in the mid-century infrastructure boom or to comply with the Clean Water Act requirements of the 1970s are reaching the end of their useful life. That’s on top of the massive programs to replace lead and copper lines, the need to procure more water in drought-prone areas, and the cost of adapting infrastructure to cope with extreme weather from climate change.

According to the National Association of Clean Water Agencies (NACWA), water rates have risen faster than inflation since 2002.

And for customers on fixed incomes, even small increases can make a huge difference for their budgets.

“When we think about affordability, we’re not concerned about whether it’s expensive for someone to water their lawn. We want to know that people can cook, shower, clean, flush their toilets…the basic necessities,” says Manny Teodoro, an associate professor in the political science department at Texas A&M University.

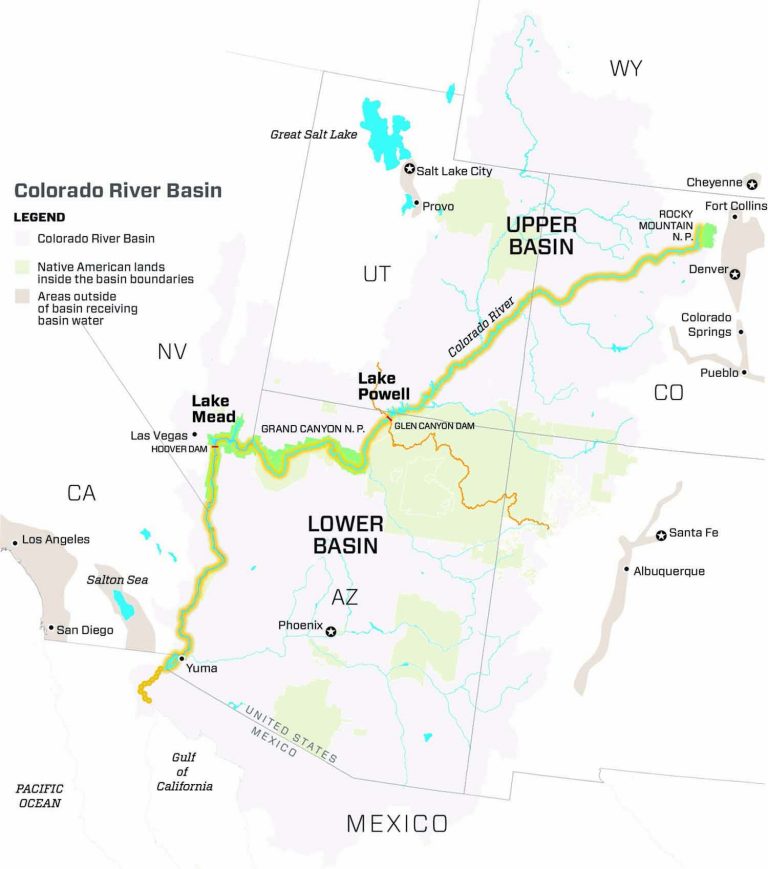

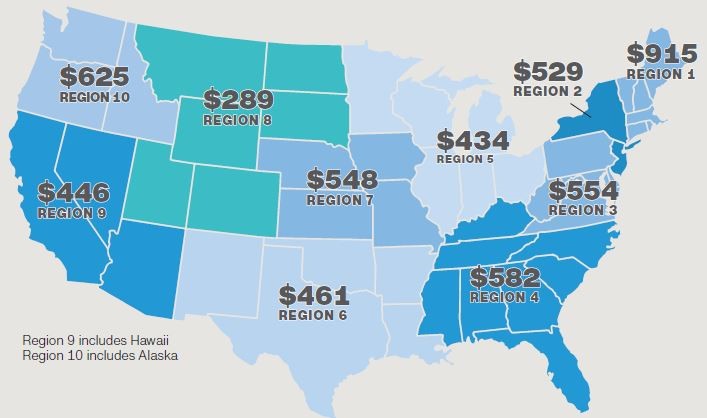

States are grouped by EPA region. Colorado is in EPA Region 8, where the average annual wastewater charge in 2018 was $289—less than other regions.

According to Denver Water spokesman Todd Hartman, most households the utility serves pay less than 1 percent of their income for water. Denver Water does not have specific numbers on how many households pay more than 1 percent for drinking water, Hartman says, but added that, “Socioeconomic conditions in the Denver Water service area compare favorably to U.S. averages and have continued to improve in recent years.”

But with costly repairs coming due, it will take a concerted effort to maintain high-quality infrastructure and deliver quality water, while keeping rates from ballooning in a way that disproportionately affects lower-income families.

In Colorado, drinking water infrastructure needs are estimated at more than $10 billion, according to the 2020 Colorado Infrastructure Report Card from the American Society of Civil Engineers, with a chunk of that cost going back to ratepayers. That’s prompted discussions about how to best fund those repairs—and how to make sure that no customer feels an unfair burden when utilities need more capital.

“The question of the [utility] bill has always been there, but it’s becoming more and more significant,” says Andrew Rheem, a senior manager with the Colorado-based consulting firm Raftelis, which has worked with utilities in Boulder, Greeley and Denver. “How it gets addressed is going to continue to evolve, but right now a lot of communities are just wondering how to find any solution.”

The cost of water

When water affordability enters the national conversation, it’s usually because of a crisis.

In 2014, the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department took an extraordinary step: In order to recoup unpaid bills, it shut off running water to more than 30,000 low-income households who were behind on payments. As the utility worked to put customers on a payment plan and restore service, the action drew a rebuke from around the world; even the United Nations sent a delegation to the city and deemed it “contrary to human rights.”

Traditionally, governments and utilities, including Denver Water, determine affordability with the EPA calculation that compares water and wastewater bills to a region’s median household income (MHI). If drinking water doesn’t exceed 2.5 percent of MHI and wastewater doesn’t exceed 2 percent, they are considered affordable.

According to Texas A&M’s Teodoro, the working poor are paying roughly 10 percent of their income on water nationally. That number could rise if economic trends continue.

“In a lot of communities, things like rent and energy are going up faster than incomes are,” Teodoro says. “Both the numerator and the denominator are going in the wrong direction.”

Most of the pain, however, is likely to be felt in the American South, where incomes are lower and infrastructure is in more desperate need of repair. Cities in the Northeast, where pipes can date back to the early 1900s and the income gap is wider, are also in greater danger.

Elizabeth Mack, who authored the MSU study, says affordability is posed to be a “burgeoning crisis.” It already weighs on households that are struggling with high rents, energy bills and food costs, but could soon rise even more.

“You can start seeing problems affecting households we consider lower-middle income,” Mack says. “These households are already squeezed from a variety of perspectives. If incomes were going up a lot, this might not be an issue, but they’re just not.”

The crisis also breaks along color lines. In a 2019 report, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People found “a clear connection between racial residential segregation and black access to water systems,” including rising rates that disproportionately affected black neighborhoods.

The West, however, has largely avoided those problems. In Teodoro’s national analysis, he found that Western states had, on balance, more affordable rates than the rest of the country. NACWA’s annual Cost of Clean Water Index found that EPA Region 8 (Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Montana, North Dakota and South Dakota) had the lowest average wastewater charge of any region, with a $289 annual average compared to the $504 national figure.

That’s in part because of less urgent infrastructure needs. Although much of Colorado’s water infrastructure dates back to at least the 1960s, it’s still in better shape than pipes and treatment plants in other parts of the country. The American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that Colorado needs $10.19 billion in drinking water infrastructure improvements over the next two decades, a huge bill but less than other states like Pennsylvania ($16.77 billion), Alabama ($11.26 billion), and Ohio ($13.41 billion).

Even areas where income levels could signal affordability challenges have kept water rates low. The San Luis Valley was a high-risk tract in Mack’s study, based on median income, but rates in the City of Alamosa are not a serious burden for residents. Heather Brooks, city manager for Alamosa, said the city has, if anything, kept rates too low to cover capital costs. A half-cent sales tax dedicated to water infrastructure has helped defray those costs.

Pueblo Water spokesman Joe Cervi likewise said that the utility has lowered costs by keeping a lean staff and planning ahead for major repairs. According to city data, the average bill for 11,000 gallons is $53.15, well below the Front Range average of $62.82.

A helping hand

Often, affordability can butt up against one of the biggest priorities for Colorado utilities: conservation. In 2014, Longmont Water decided to encourage conservation by charging customers based on use, rather than the lifeline rate that charged everyone the same amount for their first 2,000 gallons. There was concern, however, that the change could punish families who need lots of water to shower and cook, says Becky Doyle, a rate analyst and manager for the City of Longmont’s Department of Public Works and Natural Resources.

“A grandma who lives by herself can keep the water bill low, but that’s not the only kind of low-income household composition we need to be worrying about,” Doyle says. “Low-income households aren’t all low water users.”

Longmont already had a rebate program for fixed-income seniors, but extended that benefit to any household eligible for the Low-income Energy Assistance Program (LEAP). But, in a sign that water isn’t top of mind for many households, only two additional applicants signed up in the first year. Expanded outreach has garnered about 130 participants, but Doyle acknowledged that’s still not everyone.

Facing much-needed infrastructure repairs, other utilities across the state have sought to blunt the impact to customers with their own expanded assistance programs. Denver Water, for example, has some 140 projects planned for the next five years, which call for higher customer bills. After a rate increase in 2019 that added roughly 55 cents per month for urban customers (the increase was between $1.90 and $3.40 per month for suburban households), the board has approved another increase for 2020 that will add about a dollar more per month. (For suburban households, the increase will be between $1.15 and $1.36.)

The increases to the fixed monthly charge, which is associated with the meter size, are being done slowly to even out revenues year to year, and to limit the impact on the community, the utility says. Denver also uses a three-tiered charge and assesses indoor use, such as flushing toilets, cooking and bathing, at the lowest rate to reduce the burden on low-income families that, say, won’t pay for watering a lawn. The lowest rate is also measured during the winter, reflecting “essential, nondiscretionary usage,” Denver Water says.

Denver Water also offers assistance, like a one-time courtesy cancellation and payment extension for water shutoffs after delinquent payments and a pilot partnership with Mile High United Way to provide one-time bill relief and like other utilities has pledged to suspend shutoffs to help protect those who’ve lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic.

Elsewhere, utilities are exploring income-based structures that would ensure that the poorest families face the lowest cost burden. Philadelphia in 2017 rolled out a first-in-the-nation structure that charged lower rates for households at or below 150 percent of the federal poverty line, which some experts predicted would actually increase revenues by reducing missed or late payments. Baltimore, where some poor black residents have complained of triple-digit bills, has also debated a similar structure, and advocates are watching closely to see if the model could be expanded to more cities that are facing payment crises.

Is there a fix?

For utilities, providing service without raising rates would be easiest with an influx of federal funding. Washington has been talking about water infrastructure assistance, including through the proposed LIFT Act (Leading Infrastructure for Tomorrow’s America Act), and under some of the COVID-19 relief measures, money may be provided to help utilities offset their infrastructure costs.

And all the while, drinking water standards and infrastructure costs will only pile up. That, says MSU’s Mack, means utilities need to start planning to avoid the worst impacts.

“We can’t say what’s going to happen, but there could be some big spikes in bills if all this deferred investment comes up at one time. The risk is when that gets to households that are already being squeezed,” she says.

An earlier version of this article appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of Headwaters magazine. This story was published by Fresh Water News on April 15, 2020.

Jason Plautz is a journalist based in Denver specializing in environmental policy. His writing has appeared in High Country News, Reveal, HuffPost, National Journal and Undark, among other outlets.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org.