By Allen Best

Colorado water officials are considering whether to designate the increasingly stressed Yampa River from Steamboat Springs downstream to near its entrance into Dinosaur National Monument as over-appropriated.

If approved by the state water engineer, the designation would require augmentation plans for larger-volume wells along the river from Steamboat to Lilly Park, where the Little Snake River flows into the Yampa.

Augmentation plans document how the water used will be replaced to satisfy senior water rights. Such water is typically delivered from upstream reservoirs, both large and small.

The proposal comes amid growing evidence that the Yampa River can no longer deliver water to all users all the time as they wish. There have been two “calls” on the river in the past three years, limiting diversions of users with later — or junior — diversion decrees until those of older or more senior decrees are satisfied.

The changed hydrology of the river can best be understood at the gauging station along U.S. Highway 40 near Maybell. There, according to Division 6 Engineer Erin Light, annual flows a century ago of 1.5 million acre-feet annually have declined to 1.1 million acre-feet annually. The gauge during one year in the past decade recorded only 500,000 acre-feet.

Light is proposing the over-appropriation designation. When the comment period will begin and how long it will extend has not been determined.

“An existing water right is not going to be injured by this over-appropriation designation,” Light said on a video conference meeting Monday evening with more than 100 viewers. “They would be protected.”

Colorado law considers all groundwater to be tributary to the stream system unless proven otherwise. As Light recently explained to the Yampa/White/Green Basin Roundtable, when a stream system is over-appropriated, drawing water from a well can deplete the stream during times when the water in the stream is insufficient to satisfy all decreed water rights.

The Yampa River famously long had sufficient flows such that it lacked the close supervision of many of the state’s rivers, including all of those on the east slope.

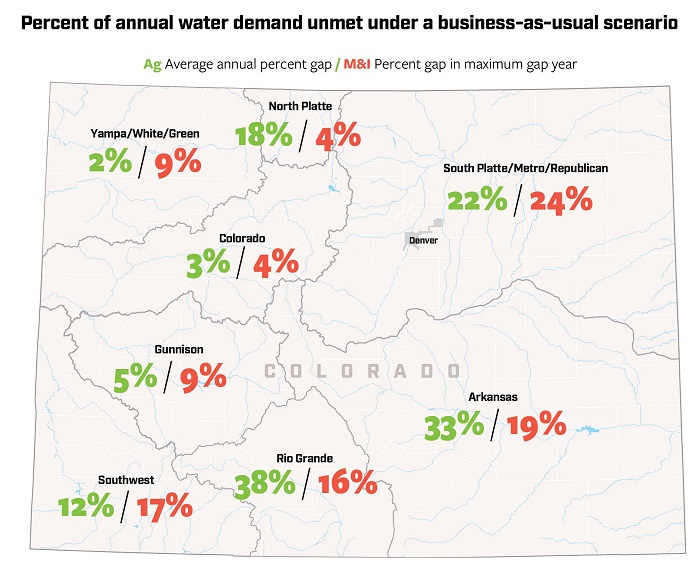

“If you look at the South Platte, the Rio Grande and the Arkansas, these are basins where the surface water was over-appropriated 100-plus years ago,” said Kevin Rein, the state engineer. He will be making the decision whether to approve Light’s recommendation.

Only a few of Colorado’s rivers, mostly on the flanks of the San Juan Mountains, remain free of restrictions that require augmentation plans for wells along rivers as are now proposed for the Yampa.

Regulation of large-capacity wells began in Colorado during the 1960s. The laws were adopted in response to conflicts in the South Platte River Valley between farmers diverting water directly from the river and those drilling wells. State legislators clarified the legal rights of each. The key breakthrough was acceptance that groundwater was, in many cases, part of the same water system as the surface flows.

In the Yampa River valley, this designation would primarily impact new residential wells located on lots less than 35 acres and wells used for purposes other than domestic uses.

Permits for new wells located on lots of less than 35 acres in existing subdivisions may be issued for in-house use. If the well serves additional purposes, such as for livestock watering or a pond that intercepts groundwater on a lot less than 35 acres, then an augmentation plan must be in place before a well permit will be issued.

Well permits may be issued for as many as three single-family dwellings, irrigation of as much as 1 acre of lawn and garden, and for watering of domestic animals, on lots greater than 35 acres.

Based on her experience after designations of the Elk River and the Yampa River upstream of Steamboat Springs in the past decade, Light expects to see no major impacts.

“I have just not seen a tremendous impact on people because of this designation,” she said.

Stagecoach Reservoir, near Oak Creek, has several thousand acre-feet of its 36,000 acre-feet of storage capacity available for augmentation. YamColo, a smaller reservoir located on the Bear River, upstream from Yampa, has lesser quantities available. Both are administered by the Upper Yampa Water Conservancy District, whose boundary goes to but does not include Craig.

How much augmentation water will be needed from upstream reservoirs will depend upon the use, explained Holly Kirkpatrick, external affairs manager for the district. Does the well provide for livestock water, for example, and if so how many animals?

The conservancy district has enough water in the two reservoirs, especially Stagecoach, to provide for all needs, at least in the near term.

“Individual augmentation plans are of very small magnitude,” said Andy Rossi, general manager. “We might be talking about less than one acre-foot up to three acre-feet” (annually), he said of augmentation plans for new wells.

Traditional agriculture water users would normally seek storage rights in the reservoirs for larger volumes.

New paradigm

It will still be possible to file for new water rights in the Yampa subject to Colorado’s first-in-time, first-in-right pecking order. But the proposal signals a new paradigm for the full Yampa River Basin.

“It should be a clear indicator to those individuals establishing a new appropriation that water may not be available all of the time every year to meet their water needs,” Light said.

One of the key water rights in determining water use upstream are those at Lilly Park.

Twice in the past three years those rights have triggered “calls” on the Yampa River upstream, causing Light, as the water engineer, to require more junior users upstream to end their diversions. That same call could have been made in 2002, but the owner of the water rights at Lilly Park recently confided to Light that he didn’t want to cause the problems upstream in that notoriously dry year.

Enlargement of Elkhead Reservoir, near Hayden, has also allowed more water to be delivered downstream, forestalling the need for the designation of over-appropriation.

The Yampa River upstream of Steamboat Springs and many of its tributaries were previously designated as over-appropriated after a water decree for a recreational in-channel diversion for the kayak park in Steamboat Springs was granted in 2006.

For Steamboat Springs, one consequence was the need to create an augmentation plan for the wells along the Yampa River supplying its water treatment plant. The water from Stagecoach will be needed only if the river downstream is on call, meaning that Steamboat’s water diversions must be curtailed to meet needs of senior users.

Will the over-appropriation designation downstream of Steamboat impact the city’s water supplies?

“No, not that I’m aware of,” said Kelley Romero-Heaney, the city’s water resources manager.

The designation of over-appropriation “just means there’s more accountability” to ensure that new diversions don’t injure existing water users and water-right holders, Romero-Heaney said.

The state also designated the Elk River, north of Steamboat, as over-appropriated Jan. 1, 2011, just a few months after the first call. Water is available from Steamboat Lake for augmentation.

Small reservoirs have also been constructed to deliver augmentation water in the Elk River basin. Small augmentation reservoirs may be needed for new development downstream from Craig, such as for new rural subdivisions.

Light, in recommending the over-appropriation designation, identified no single trigger.

There were the two calls, critical low-flows in other years, and the increasing importance of juggling reservoir releases. She said the most important signal of a new era came in 2018, when the first call was placed on the river.

“I think you could make a good case of climate change and different ecological conditions,” said Rossi. Snowfall remains highly variable, but runoff has consistently arrived earlier followed by more intense heat and, perhaps, a later arrival of winter.

Soil moisture may also be a factor. If soils are dry going into winter, they’ll soak up more of the runoff.

“Start the season with dry soils, and that is the first bucket that needs to be filled when the snow starts melting,” Becky Bolinger, the assistant state climatologist for Colorado, explained last week in The Washington Post.

These changes were evident in 2020. Winter snows were healthy and the snow water equivalent, or the amount of water in the snow once it has melted, was 116% of median. Then came spring, early and warm. By June, the snow-water equivalent of the remaining snowpack had dropped to 69%.

Then came summer, hot and mostly absent rain. August broke records for both the hottest and driest summer month on the 130-year record. This combination of heat and lack of precipitation actually made 2020 worse than the other notorious drought years of recent memory: 2002, 2012 and 2018, according to Romero-Heaney

Designation of over-appropriation, however, would not forecast the climate in the Yampa Valley, cautioned Rein.

“It just recognizes what has been happening recently,” he said.

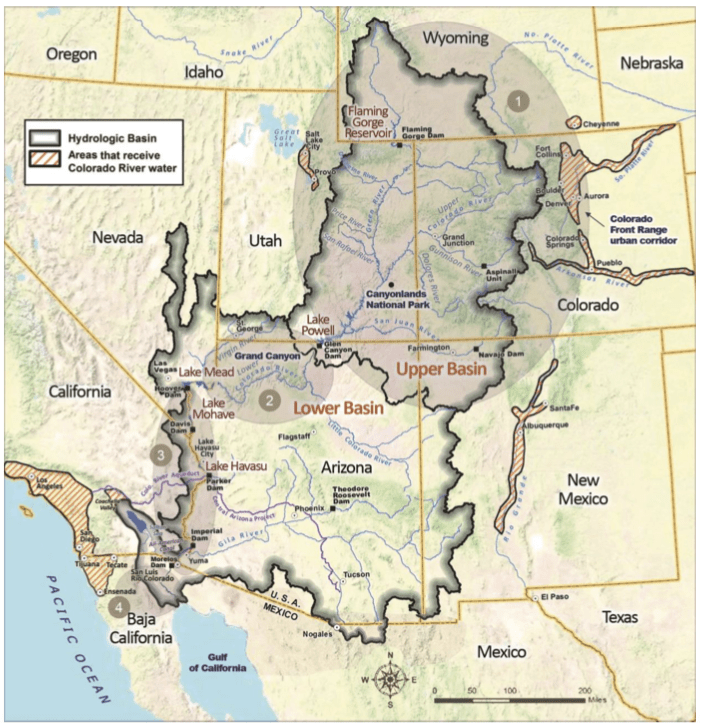

Climate change has started playing a significant role in declining river flows and falling reservoir levels in the Colorado River basin. These declines have led to concerns in Colorado during the last 20 years that requirements of the compact governing the Colorado River and its tributaries in the seven basin states could force curtailment of water use within Colorado.

From his perspective in Denver, Rein sees the proposed designation on the Yampa being neutral. All groundwater is already considered tributary to the river and hence should have no additional impact on compact compliance matters.

Aspen Journalism covers water and rivers in collaboration with the Steamboat Pilot & Today and other Swift Communications newspapers. This story ran in the March 10 edition of the Steamboat Pilot & Today.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.