Fifteen years ago, a landmark legal settlement brought almost a billion dollars in funding to revitalize a badly degraded San Joaquin River. Take a tour of ongoing efforts by the US Bureau of Reclamation, an unlikely savior, and conservation groups to ease the passage of salmon and trout from the Pacific Ocean to a vital 150-mile stretch of the river below the Sierra Nevada. This interactive map was produced in collaboration with The Water Desk at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The San Joaquin

Reimagining a River

California’s San Joaquin River flows from the Sierra Nevada to the Pacific Ocean. At just over 350 miles, it is California’s second-longest waterway. But by the measure of the ecological damage it has sustained, it has no rival.

This map is a visual narrative of that history and the ambitious effort to restore the river and its iconic species, the Chinook salmon.

Scroll to continue.

The San Joaquin

Reimagining a River

California’s San Joaquin River flows from the Sierra Nevada to the Pacific Ocean. At just over 350 miles, it is California’s second-longest waterway. But by the measure of the ecological damage it has sustained, it has no rival.

This map is a visual narrative of that history and the ambitious effort to restore the river and its iconic species, the Chinook salmon.

Scroll to continue.

The San Joaquin

America’s Most Endangered River

In 2014, the environmental group American Rivers named the San Joaquin “America’s Most Endangered River.” The river has been devastated by dams and water diversions delivering the bulk of the river’s flow to the region’s farms and cities.

This change has been devastating to migratory fish populations like salmon, steelhead, and sturgeon and other species dependent on wetland ecosystems.

The lower San Joaquin flows through a mosaic of farmlands in the Central Valley. Water Education Foundation

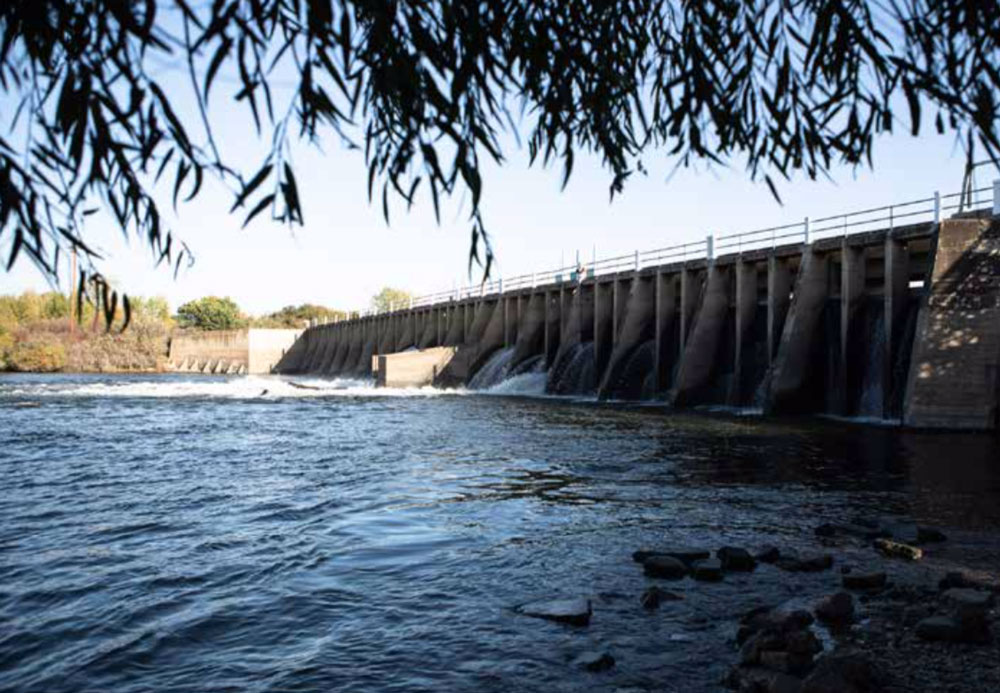

Friant Dam

The Great Barrier

Friant Dam is the ultimate barrier to salmon on the San Joaquin River. Constructed in the late 1930s as part of the Central Valley Project, the dam dramatically altered the hydrology of the San Joaquin, shunting most of the river’s flow into the Friant-Kern Canal, which today delivers water to more than a million acres of farmland and a quarter of a million people in the Central Valley.

Construction of Friant Dam, a centerpiece of the Central Valley Project, began in 1939 and finished in 1942. Friant Water Authority

Friant Dam

The Great Barrier

Friant Dam is the ultimate barrier to salmon on the San Joaquin River. Constructed in the late 1930s as part of the Central Valley Project, the dam dramatically altered the hydrology of the San Joaquin, shunting most of the river’s flow into the Friant-Kern Canal, which today delivers water to more than a million acres of farmland and a quarter of a million people in the Central Valley.

Construction of Friant Dam, a centerpiece of the Central Valley Project, began in 1939 and finished in 1942. Friant Water Authority

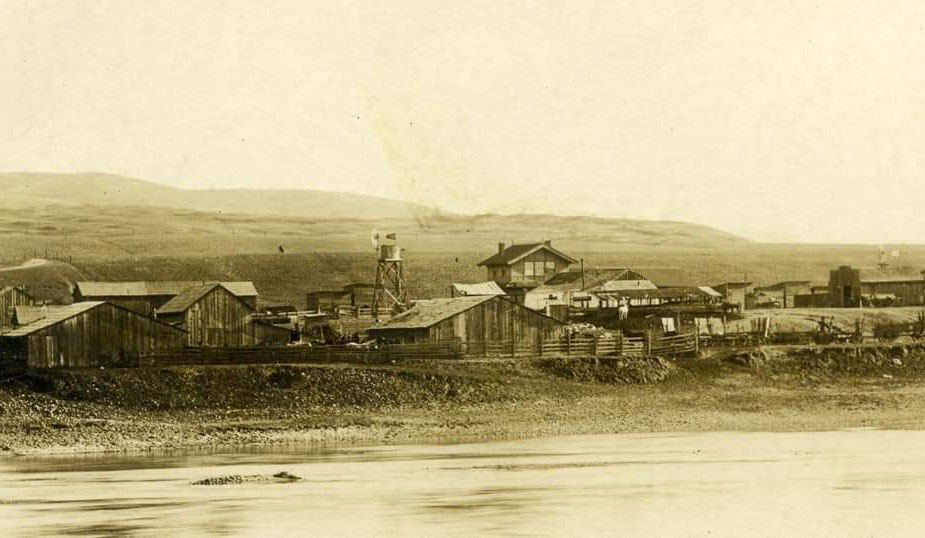

Millerton, California

A Town, Drowned

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, steamboats could pass up the San Joaquin River as far as this now-vanished settlement. Before its impoundment, the river could reach spring flows of 10,000 cubic feet per second or more.

The former riverside town of Millerton was submerged under the reservoir that bears its name. Millerton Lake State Recreation Area

Millerton, California

A Town, Drowned

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, steamboats could pass up the San Joaquin River as far as this now-vanished settlement. Before its impoundment, the river could reach spring flows of 10,000 cubic feet per second or more.

The former riverside town of Millerton was submerged under the reservoir that bears its name. Millerton Lake State Recreation Area

Upper San Joaquin River and Tributaries

Denied Access

The construction of Friant Dam cut the San Joaquin River in two, denying Chinook access to their historic spawning grounds in the river’s high-elevation tributaries. This loss of habitat led to a calamitous crash in salmon populations.

Thousand Island Lake, a favorite destination of backpackers, marks the spectacular headwaters of the San Joaquin. Flickr User Marty B

Upper San Joaquin River and Tributaries

Denied Access

The construction of Friant Dam cut the San Joaquin River in two, denying Chinook access to their historic spawning grounds in the river’s high-elevation tributaries. This loss of habitat led to a calamitous crash in salmon populations.

Thousand Island Lake, a favorite destination of backpackers, marks the spectacular headwaters of the San Joaquin. Flickr User Marty B

Bureau of Reclamation Restoration Area

A Landmark Restoration

In 2006, a landmark settlement was reached between environmental groups and the Bureau of Reclamation requiring the agency to restore a self-sustaining population of Chinook salmon below Friant Dam.

Fifteen years on, the effort has met resistance, particularly from agricultural interests in the valley. But the San Joaquin and its salmon have also shown tantalizing signs of rebirth.

Restoration scientists check a rotary screw trap for migrating salmon. San Joaquin River Restoration Program

Bureau of Reclamation Restoration Area

A Landmark Restoration

In 2006, a landmark settlement was reached between environmental groups and the Bureau of Reclamation requiring the agency to restore a self-sustaining population of Chinook salmon below Friant Dam.

Fifteen years on, the effort has met resistance, particularly from agricultural interests in the valley. But the San Joaquin and its salmon have also shown tantalizing signs of rebirth.

Restoration scientists check a rotary screw trap for migrating salmon. San Joaquin River Restoration Program

Reach 1A

New Spawning Grounds

The 25-mile stretch of river below Friant Dam is a key part of the San Joaquin restoration. Known as Reach 1A, this stretch of river is supplied with cold water coursing from the bottom of Friant Dam and provides restored salmon populations with viable spawning habitat.

A verdant stretch of the San Joaquin known as Reach 1A is critical spawning habitat for Chinook salmon. Jeremy Miller

Scout Island

A Vital Refuge for Fish and People

Along Reach 1A are small areas of riparian vegetation that once filled the lower reaches of the San Joaquin River. These areas provide habitat for spawning salmon and dozens of other species of birds, mammals, and plants. They are also coveted by locals, who flock to the river in large numbers during summer to escape the heat.

Recreationists enjoy the cold waters of the San Joaquin River on the outskirts of Fresno. Jeremy Miller

Scout Island

A Vital Refuge for Fish and People

Along Reach 1A are small areas of riparian vegetation that once filled the lower reaches of the San Joaquin River. These areas provide habitat for spawning salmon and dozens of other species of birds, mammals, and plants. They are also coveted by locals, who flock to the river in large numbers during summer to escape the heat.

Recreationists enjoy the cold waters of the San Joaquin River on the outskirts of Fresno. Jeremy Miller

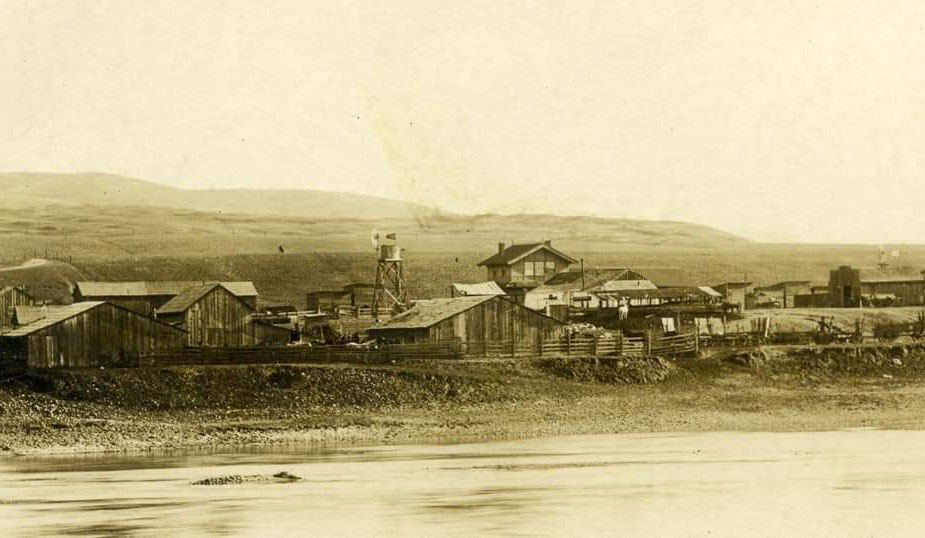

Mendota Dam

Giving Salmon a Way Around

Mendota Dam, built in 1919, is among the most serious barriers facing salmon and other migratory fish species in the lower river. It is also the site of the priciest and most complex project of the San Joaquin River restoration. When complete, Reach 2B will incorporate a large bypass channel that will allow spawning salmon upstream and juvenile fish to avoid the dam.

Mendota Dam is an antiquated structure on the lower San Joaquin that blocks the passage of salmon and other migratory fish. Mette Lampkov

Eastside Bypass

Loosening the Straitjacket on the San Joaquin

Over the years, engineers transformed large stretches of the river, including the Eastside Bypass, from a meandering waterway into a linear water conveyance system. These changes had drastic consequences for salmon as well as dozens of other wetland species. In low-water years, salmon must be captured and hauled in trucks around these choke points to Reach 1A, below Friant Dam. While the restoration does not call for the removal of the bypass altogether, it seeks to make it more navigable for fish.

Along much of its lower section, the once sinuous riverbed of the San Joaquin has been hemmed into linear concrete canals. Jeremy Miller

Eastside Bypass

Loosening the Straitjacket on the San Joaquin

Over the years, engineers transformed large stretches of the river, including the Eastside Bypass, from a meandering waterway into a linear water conveyance system. These changes had drastic consequences for salmon as well as dozens of other wetland species. In low-water years, salmon must be captured and hauled in trucks around these choke points to Reach 1A, below Friant Dam. While the restoration does not call for the removal of the bypass altogether, it seeks to make it more navigable for fish.

Along much of its lower section, the once sinuous riverbed of the San Joaquin has been hemmed into linear concrete canals. Jeremy Miller

Along much of its lower section, the once sinuous riverbed of the San Joaquin has been hemmed into linear concrete canals. Jeremy Miller

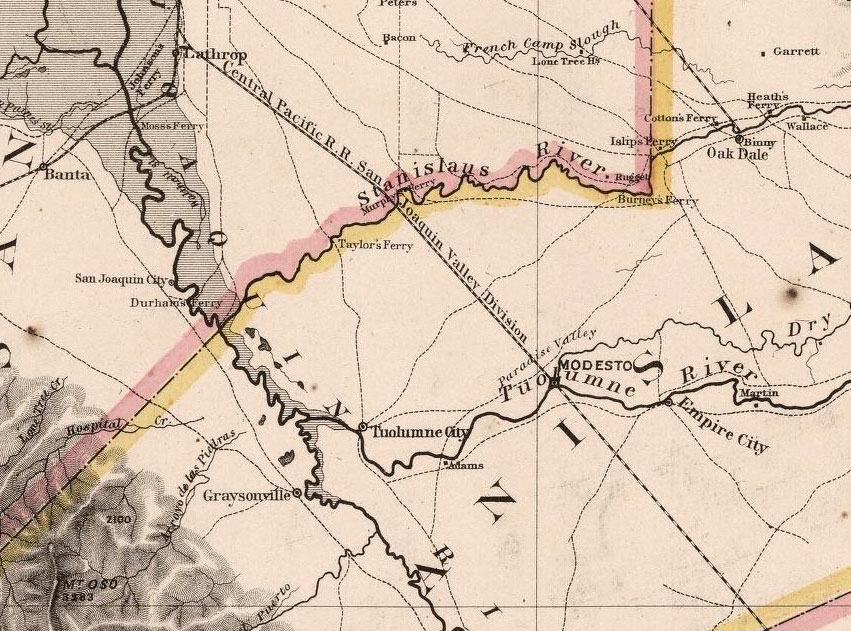

Confluence with Tuolumne River

A Watery World

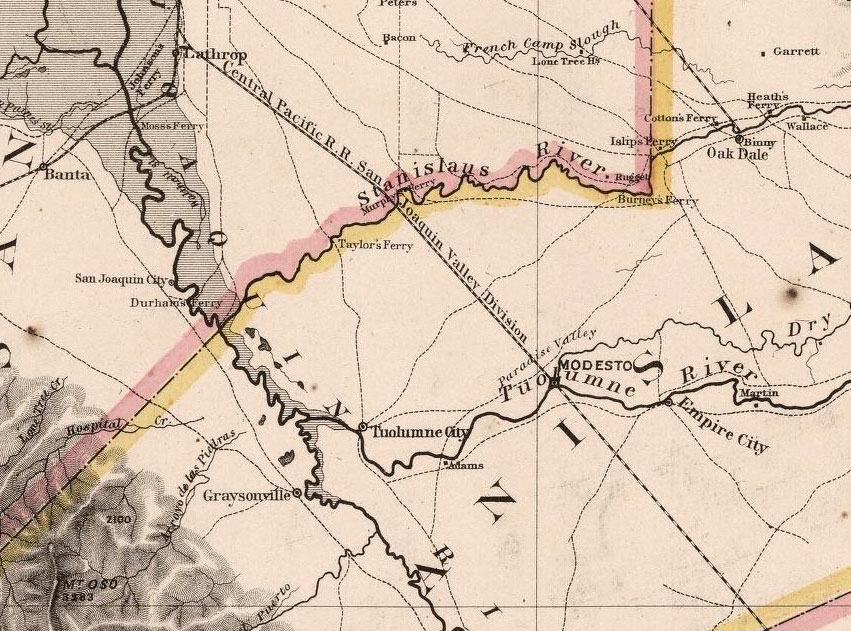

One can get a sense of the pre-engineered San Joaquin in the writings of John Muir. In a journal entry from November 1877, Muir wrote of a watery landscape in which “salmon in great numbers … [made] their way up the river for the first time this season.” Muir also noted the presence of “mud” from hydraulic gold mining operations miles upstream, hinting at the multitude of impacts to come.

The confluence of the Tuolomne and San Joaquin Rivers was once part of a Mexican land grant called El Pescador (the fisherman). David Rumsey Map Collection

Confluence with Tuolumne River

A Watery World

One can get a sense of the pre-engineered San Joaquin in the writings of John Muir. In a journal entry from November 1877, Muir wrote of a watery landscape in which “salmon in great numbers … [made] their way up the river for the first time this season.” Muir also noted the presence of “mud” from hydraulic gold mining operations miles upstream, hinting at the multitude of impacts to come.

The confluence of the Tuolomne and San Joaquin Rivers was once part of a Mexican land grant called El Pescador (the fisherman). David Rumsey Map Collection

Dos Rios Wetland Restoration

Remaking the San Joaquin’s Wetlands

Today, at the confluence of the San Joaquin and Tuolumne Rivers, an ambitious restoration project is underway to restore the kind of wetland habitat that Muir would have seen nearly 150 years ago. The Dos Rios Ranch Preserve, overseen by the nonprofit River Partners, seeks to restore a 2,100-acre parcel of wetland. Since acquiring the property in 2012, River Partners has restored 1,600 acres of the Dos Rios allotment.

The Dos Rios Restoration encompasses 2,100 acres of riverside farmlands being transformed into wetland habitat. River Partners

Dos Rios Wetland Restoration

Remaking the San Joaquin’s Wetlands

Today, at the confluence of the San Joaquin and Tuolumne Rivers, an ambitious restoration project is underway to restore the kind of wetland habitat that Muir would have seen nearly 150 years ago. The Dos Rios Ranch Preserve, overseen by the nonprofit River Partners, seeks to restore a 2,100-acre parcel of wetland. Since acquiring the property in 2012, River Partners has restored 1,600 acres of the Dos Rios allotment.

The Dos Rios Restoration encompasses 2,100 acres of riverside farmlands being transformed into wetland habitat. River Partners

San Joaquin–Sacramento River Delta and Beyond

Challenges Beyond

The perils for salmon extend beyond the river and into the great estuary, or delta, formed at the confluence of the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers. Massive pumps delivering water to the aqueducts of the State Water Project have altered the river’s salinity and harmed migrating salmon, which depend on water chemistry for navigation. Collapsing marine ecosystems in San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean—driven by climate change, overfishing, and pollution—have also seriously imperiled the recovery of the San Joaquin’s salmon population.

A coproduction of Sierra Magazine and The Water Desk

Written and produced by Jeremy Miller and Geoff McGhee/The Water Desk

Supported by a grant from The Water Desk, part of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Map sources: United States Bureau of Reclamation; River Partners