By Natalie Keltner-McNeil

Since state officials began a more focused monitoring effort six years ago to detect toxic algae blooms in Colorado’s lakes and reservoirs, testing has documented harmful levels of such toxins three times on the Western Slope.

Two of those toxic blooms occurred in Routt County reservoirs — first at Stagecoach Reservoir in 2019 and then at Steamboat Lake last summer, which was the first year that state park managers were required to regularly test for toxic algae. Results showing bacteria above state thresholds caused a two-week swimming closure at the popular state park.

Since 2014, toxic algae has been discovered in nine Front Range lakes or reservoirs, while the only other Western Slope bloom was found in 2018 at Fruitgrowers Reservoir in Delta County.

More research is needed to determine the causes of these recent blooms. But an increase in testing due to more stringent Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) toxic algae monitoring protocol, a history of ranching around and on reservoir land, and climate change are probably contributing to the increase in recorded toxic blooms on the Western Slope.

Steamboat Lake State Park manager Julie Arington said the updated CPW monitoring and testing guidelines influenced the discovery of the toxic bloom last summer. The new guidelines, which were updated going into the season, require park managers to regularly test for toxins May through September, according to CPW officials.

“It may have been there before (this year), but we just didn’t notice it. We hadn’t been testing for it,” Arington said. But in mid-August, when water temperatures were at their warmest, toxin levels were found to be above the recently-established thresholds and park managers shut down the lake to swimming for two weeks, until winds and cooler temperatures slowed the blooms down.

Blue-green algae that populate lakes in and of themselves are not harmful and form the basis of the riparian food web. Under certain conditions, however, the algae multiply rapidly, form blooms and produce toxins.

Nutrients and warming cause these blooms, said Jill Baron, a research ecologist and senior scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey. “Period.”

Toxic algae feed off phosphorus and nitrogen, nutrients sourced from fertilizers, vehicle emissions, sewage, soil, animal excrement and plant material. If ingested in levels above state health standards, the toxins cause sickness, liver and brain damage when ingested during recreational lake activity or when drinking contaminated water.

Tracing Steamboat and Stagecoach nutrients

Steamboat and Stagecoach reservoirs sit in the greater Yampa basin to the north and south, respectively, of Steamboat Springs. Steamboat Lake, which holds 23,064 acre-feet of water, is portioned off a creek that feeds into the Elk River, a tributary of the Yampa. Stagecoach, which holds 36,439 acre-feet of water, is a dammed section of the Yampa River.

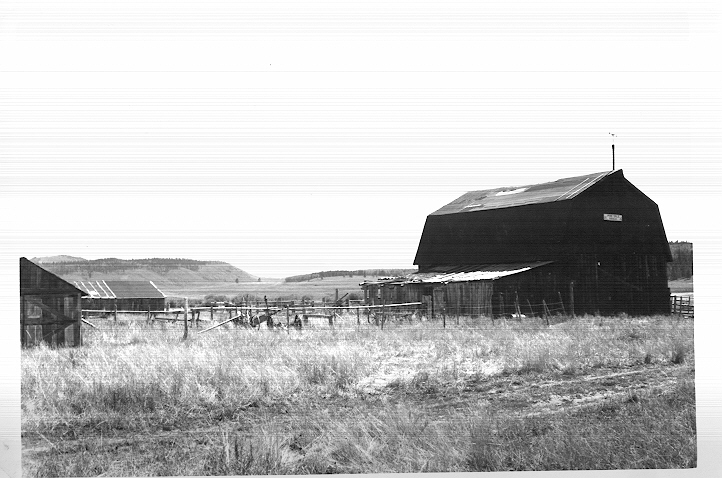

Nutrients deposited at the bottom of both reservoirs from decades of ranching probably contribute to the blue-green algae blooms. By the early 1880s, settlers were ranching in the Yampa Valley, including the lands that would become Stagecoach and Steamboat reservoirs, said Katie Adams, curator for the Tread of Pioneers museum.

Steamboat Lake was constructed in 1967 with funds from the operators of Hayden Station power plant and the Colorado Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation. It became a state park in 1972.

The former ranch lands where Stagecoach is today were bought in 1971 by the Woodmoor Corporation, which planned to build a residential and recreational community with ski areas and golf courses, but the company went bankrupt in 1974. The site was later bought and developed by the Upper Yampa Water Conservancy District and power companies, which funded the reservoir’s construction in 1988. So, for decades leading up to the post-war era, cattle excrement was enriching the reservoir lands with nitrogen and phosphorus — nutrients that fuel the growth of blue-green algae.

Those involved in planning and constructing Stagecoach Reservoir were told algae blooms were a likelihood, said Stagecoach State Park manager Craig Preston.

“Even when they were going through the (construction) processes, they were told there would likely be algae situations, because of the nutrients in the soil,” Preston said.

Baron agrees that nutrients at the bottom of both lakes probably contribute to the blooms.

“They basically took a meadow and turned it into a lake. So, all that vegetation and organic matter on the bottom of that meadow is slowly decomposing and putting its nutrients into the lake itself,” Baron said.

Researchers are focusing on the region to determine which specific sources of nitrogen and phosphorus prompt harmful algal growth. The USGS has been collecting data on algae compositions in Stagecoach Reservoir and in the greater Yampa River watershed and will analyze possible sources of blue-green algae as part of the report, USGS hydrologist Cory Williams said. The results of the study will be published in February or March, according to Williams.

Origins and evolution of state protocol and monitoring

CPW began drafting toxic-algae protocol the summer of 2014, after a local agency found microcystin — a toxin commonly produced by blue-green algae — in Denver’s Cherry Creek Reservoir, said CPW Water Quality Coordinator Mindi May.

“At the time, we didn’t know what the numbers meant. So, we started looking around for state or federal thresholds, and there just weren’t any,” May said.

That same summer, a toxic bloom in Lake Erie contaminated the drinking water of 400,000 residents, forcing officials in Toledo, Ohio, to cut off water for three days. After these two events, May asked Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment staff to develop toxic-algae thresholds for drinking water and recreation, and traveled to state parks in 2015 to encourage staff to test for — and monitor — toxic algae during summer months.

CDPHE developed protocol and thresholds for toxic algae in 2016, based on Environmental Protection Agency standards created in 2014. The thresholds dictate the maximum amount of toxins that lakes can contain, including 8 micrograms per liter for microcystin and saxitoxin, and 15 micrograms per liter for anatoxin and cylindrospermopsin. If lakes cross this threshold, state park managers must post danger signs and close the lake to activities involving bodily contact with the water until tests show that toxins fall below harmful levels, May said.

In 2018, the CDPHE developed a database to compile monitoring and testing efforts in Colorado reservoirs and track the occurrence of toxic-algae blooms since 2014. Data from park managers’ toxin tests are included, along with data collected by CDPHE officials and other local and federal agencies, said MaryAnn Nason, CDPHE’s communications and special projects unit manager.

“We really learned a lot in those early years, and we have a lot more resources now to monitor and test for toxins,” May said of CPW’s and CDPHE’s efforts.

Western lakes lack data but will feel burn of climate change

CDPHE data shows an increase in toxic blooms from 2014 to 2020 and hints that these blooms are spreading west. Last summer recorded seven toxic blooms, compared with four in 2019 and one in 2018. Yet, increases could also be due to increased monitoring and testing over the years and due to the new 2020 protocol. For instance, 52 lakes were monitored for toxic algae in 2014, compared with 73 last summer.

More data is needed to determine how climate change and nutrients will interact to produce toxic blooms, and determine the impacts this will have on drinking water and summer recreation for high country and Western Slope lakes.

It is likely that climate change will spur more toxic blooms in the West. In a 2017 study of 27 Rocky Mountain lakes, researchers project that climate change will cause average annual lake-surface temperatures to increase 41% by 2080, with dramatically warmer water in the summer and 5.9 fewer ice-free days with each passing decade.

Warmer lakes create a widened window for toxic algae to bloom. A separate national study, also from 2017, predicts that rising air temperatures and the resultant warmer waters will increase toxic-bloom occurrence from an average of seven days per year in U.S reservoirs now to 16-23 days in 2050 and 18-39 days in 2090.

Long-term solutions for current and future blooms include placing limits on greenhouse gas, as well as nitrogen and phosphorus emissions, Baron said. Short-term solutions include waiting for blue-green algae to stop producing toxins and keeping visitors out of the water while they do, said May.

As frosty temperatures inhibit algal growth, Steamboat and Stagecoach park managers get a break from thinking about the turquoise-tinted toxins. In May, they’ll start the second season of following the parks’ new protocol, May said.

Regarding last summer’s toxic bloom, Steamboat Lake State Park’s Arington said, “I think this won’t be the last year that we see it.”

This story ran in the Steamboat Pilot & Today on Dec. 31.

This story was supported by The Water Desk using funding from the Walton Family Foundation.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism.