As the winter snowpack dissolves into spring runoff, Tony Prendergast jumps in his Toyota Tacoma and takes a bumpy ride to the headgate of an irrigation ditch in the West Elk range of southwest Colorado to release its bounty. He’s a cattle rancher and president of a ditch company that manages the water for roughly 2,000 acres, including his own, that have rights to its flow.

Like an old-time sheriff, with a greying beard and calm demeanor, Prendergast patrols the canal and tries to ensure that the ditch operates smoothly and fairly. But there’s no outlaw here to test the speed of his draw, only busy beavers building dams and forest debris in need of excavation.

Seemingly modest and hidden waterways like the ditch that Prendergast manages have become lightning rods since the Trump administration earlier this year issued a new rule that redefines what constitutes “navigable waters,” also known as “waters of the United States,” which are federally regulated under the landmark 1972 Clean Water Act. The new rule also strips away requirements for landowners to secure approval from the Environmental Protection Agency to make certain changes to their private lands.

The Trump administration’s new rule, which went into effect in June, narrows the federal government’s oversight by excluding from federal jurisdiction ephemeral streams and wetlands that are not adjacent to larger, permanent bodies of water. The change is estimated to reduce protections for more than half of all U.S. wetlands and at least 18% of all streams, according to an internal EPA presentation in 2017 that was obtained by E&E News.

In 2015, the Obama administration placed the “ephemeral stream” classification under federal jurisdiction in its “Waters of the United States” (WOTUS) rule, also known as the Clean Water Rule. Ephemeral waterways only run a few times a year, after snowmelt or big rainstorms, but they can be connected to other water bodies, either through underground or surface connections. Regardless of those connections, they are not federally protected by the Trump administration’s Navigable Waters Protection Rule, which effectively repealed the 2015 water rule. The rule-change is one of dozens of rollbacks under the Trump administration of Obama-era environmental regulations.

“I think they’re setting us way back,” said Prendergast in an interview, referring to the succession of new rules enacted by the Trump administration that diminish environmental regulations. “I don’t see any balance in their approach at all. This seesawing of policy and executive orders I think is detrimental to lasting change.” The specific water-rule change, which is now in litigation, so far hasn’t impacted his ditch or on how he runs his ranch, he added.

The new Trump rule has drawn both condemnation and praise. In the Colorado River Basin, environmentalists are concerned that the government is deregulating ephemeral streams, many of which flow from snowmelt in the mountains and contribute a huge portion of the overall water supply.

The EPA’s own Scientific Advisory Board published commentary on the rule in December 2019, concluding that the then-proposed rule “does not incorporate best available science.” That science includes a comprehensive 2015 EPA report on the connectivity of streams and wetlands, which directly informed Obama’s WOTUS rule that same year. The report shows that the pollution of ephemeral streams can cause a negative ripple effect throughout watersheds because many of the streams eventually join larger waterways.

“Our nation’s majestic waterways depend for their health on the smaller streams and wetlands that filter pollution and protect against flooding, but the Trump administration wants to ignore the science demonstrating that,” Jon Devine, director of federal water policy at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said in a press release in April announcing a lawsuit by NRDC and several other environmental groups against the U.S. EPA and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

However, many oil and gas developers, ranchers and farmers welcome the Trump administration’s rule as an overdue reprieve from more stringent Obama-era federal restrictions.

“[The new rule] provides clarity and certainty, allowing farmers to understand water regulations without having to hire teams of consultants and lawyers,” said Zippy Duvall, president of the American Farm Bureau Federation, in a press release in January.

Some cattlemen’s groups, represented by the conservative Pacific Legal Foundation, are challenging the Trump administration’s new rule for not going far enough to protect landowners and developers.

The controversy continues to play out in court. In May, a coalition of over 17 states and cities filed a lawsuit against the EPA in a bid to overturn the regulatory changes. Legal experts anticipate that the court battles will drag out well beyond Election Day.

Small streams, big waves

The rule change could have particularly large ramifications in the arid and semi-arid Southwest, where over 80% of all streams are ephemeral or intermittent, according to research from the EPA.

Ephemeral streams “flow during big rain events and big snowmelt events and are frequently dry most of the year, but that doesn’t mean they’re not important,” said Darius Semmens, a physical scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey. He is also an author of a seminal 2008 EPA-funded study that examined the importance of these waterways in the American Southwest.

Ephemeral waterways may not be as charismatic or massive as the Colorado, Columbia or Mississippi rivers, but these smaller water bodies can have an outsized impact on wildlife and humans: More than three out of every 10 Americans get some or all of their drinking water from systems that rely at least in part on intermittent, ephemeral, or headwater streams, according to the EPA.

Semmens and his colleagues concluded in their study that ephemeral streams act in much the same way as their bigger, perennial relatives. They transport nutrients and sediment throughout watersheds, provide valuable animal habitat in otherwise parched places, and recharge groundwater. The abundant ephemeral streams in the Southwest also directly contribute to perennial rivers through runoff, according to Semmens’ 2008 study as well as to more recent research, including a paper published in 2018 in the Journal of the American Water Resources Association.

Many bird species rely on ephemeral streams for refuge in arid regions. The San Pedro River in Arizona is one of these safe havens, a perennial and intermittent waterway supported by a network of ephemeral streams. Birds like the threatened Western yellow-billed cuckoo breed in the biodiversity hotspot of cottonwood-willow forests that the San Pedro and its ephemeral tendrils maintain. An analysis of the Upper San Pedro watershed by Earthjustice, an environmental law organization, estimates that 94% of the stream miles in this watershed will not be protected by the Trump administration’s definition.

“Ecosystem protection would be meaningless and ineffective if these supporting waterways were significantly degraded,” states the 2008 EPA report. The study says these arid ecosystem streams should not be given “second-class status” as compared to the waterbodies of the country’s wetter ecosystems. And yet, environmentalists argue, that’s exactly what’s happening with the new changes.

The ebb and flow of federal authority

The controversy over ephemeral streams taps into long-standing debates over the proper scope of government regulation and whether federal authority over natural resources should be delegated to the states.

“Because water quality, by and large, is regulated by the federal government and water rights are regulated by the state government, you have conflict. So it really touches a lot of hot buttons,” said John Leshy, a professor emeritus at University of California, Hastings College of the Law who served as solicitor of the Interior Department under President Bill Clinton.

Under the Trump administration’s new rule, ephemeral streams fall squarely in the states’ jurisdiction. But some scientists and environmental advocates contest that states are not prepared to take on more regulatory responsibility for water quality, and to incur the costs of implementing the regulations.

“States aren’t geared up to do that management,” said Semmens, the USGS scientist. “They don’t have the necessary expertise and infrastructure.”

The State of Colorado expressed concerns over absorbing this regulatory burden in its comment last year on the Trump administration’s revised definition of the WOTUS rule. Some federal funding given to Colorado to carry out Clean Water Act mandates is tied to the amount of water that is federally regulated within the state. A narrower definition of “waters of the United States” could mean less money to do things like issue permits and track compliance. In May, Colorado sued the EPA, arguing that the state expects to take on significant costs to develop its own state permitting program due to the rule change.

The continuous push and pull between federal and state Clean Water Act enforcement stems in part from the language of the act itself. At its inception, the act aimed to protect water quality of “navigable waters,” which it defined as “the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas.” This brief definition left unclear precisely what categories of waterways would be federally protected. Ambiguity has sowed decades of confusion among many farmers, ranchers, real estate developers and fossil fuel producers, as well as states.

Before the Clean Water Act, states oversaw all aspects of water quality and ownership. But in 1970, President Richard Nixon established the EPA in response to public outrage over widespread water pollution and government inaction. Shortly after the Act was signed into law in 1972, the EPA was given the authority to administer the law and implement pollution-control programs—some of which previously had been regulated by states. For instance, the agency required a permit for any development that could potentially pollute “waters of the United States.”

But the Clean Water Act failed to answer a critical question: What waterways should fall under that federal designation? It’s a riddle that presidential administrations and federal courts have been trying to solve ever since.

The Obama administration’s answer was to create the WOTUS rule to clarify which bodies of water automatically fall under federal protection. The rule placed ephemeral streams and many wetlands within federal jurisdiction. While the preceding George W. Bush administration took a more restrictive approach to Clean Water Act enforcement in some respects, it did not explicitly exclude all ephemeral streams from being federally regulated as the Trump administration’s rule does.

“It goes back and forth and it’s a very important question of who has the authority over water in a state,” said Rebecca Watson, former Assistant Secretary of the Department of the Interior under President George W. Bush. “Some is federal water. Some is managed by the state. Where’s that dividing line?”

Although ephemeral streams are not subject to federal regulation under the new definition of “waters of the United States,” states and landowners must still grapple with the definition of “ephemeral” itself to know which waterways are subject to deregulation and which are not. Could a certain ditch be defined as a tributary, which is federally regulated? Or is it more of an ephemeral stream, which is in the state jurisdiction? Both may have surface connections to bigger, traditionally navigable waters.

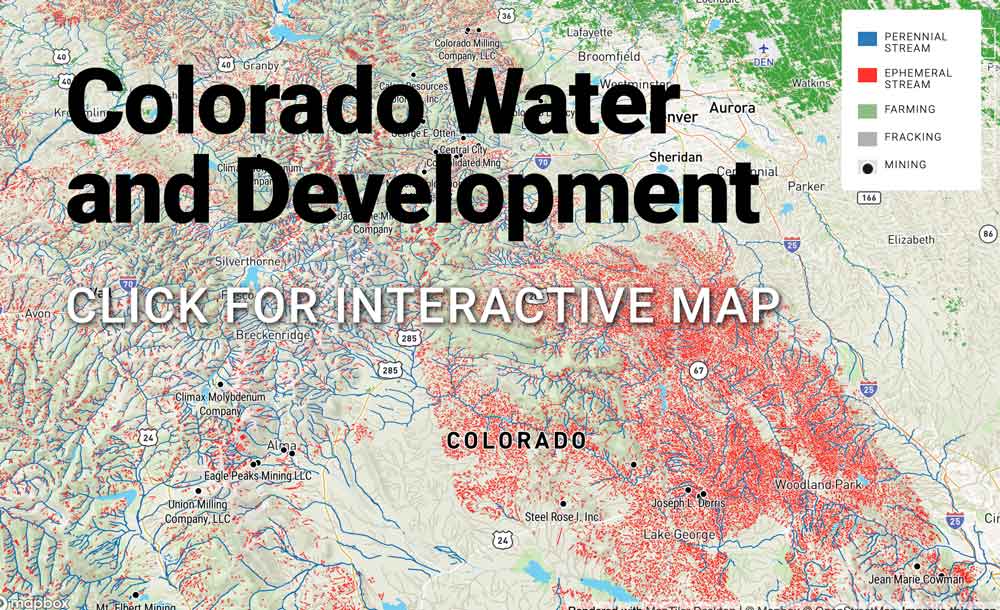

This ambiguity makes widespread identification and mapping a challenge. Kurt Fesenmyer, the GIS and conservation planning director for Trout Unlimited, said in a press release earlier this year that a major problem with the Trump administration’s new water rule is “its lack of analysis using good map data to show which streams are subject to the rule change.” He added, “That makes it hard for anyone, whether the administration or the public, to really understand the potential scope of what is at stake.” The organization last year conducted a stream data mapping analysis of the continental U.S., estimating that, on average, one mile of unmapped ephemeral streams exist for every mile of mapped stream in data from the USGS.

Trout Unlimited was one of several outdoors and sporting groups to file an amicus brief in July in support of a lawsuit to overturn the new rule. Because of the gaps in map data, TU claims that the government’s estimate of 18% of stream miles losing protections actually falls woefully short. Scientists from the organization calculated that more than half will be excluded from federal jurisdiction.

Confusion flows like water

The murky language of the Clean Water Act opened a floodgate of lawsuits trying to define “waters of the United States.” Some cases have wound their way all the way to the Supreme Court. The most recent major lawsuit in this cascade is Rapanos v. United States, which the Supreme Court took up in 2006. A divided court was unable to produce a majority opinion on whether isolated wetlands fell under federal jurisdiction. Without a majority ruling, the justices provided no definitive recommendation on how to move forward with the WOTUS definition for wetlands.

The Court’s indecision prompted the EPA to take a closer look at how waterways that aren’t permanent are or are not connected to larger, federally regulated waters of the United States. That EPA research would go on to later inform Obama’s WOTUS rule.

XK Bar Ranch, Prendergast’s 260-acre operation, near Crawford, Colo., is part grassland for grazing cattle, part piñon-juniper woodland. Two irrigation ditches run through his land, mainly supplied by the seasonal snowmelt of the Smith Fork River, a tributary of the Gunnison River, which eventually feeds into the 1,450-mile-long lifeblood of the West: the Colorado River.

Prendergast’s ditches are an example of how smaller waterways have implications downstream. The comprehensive report for the Obama-era rule emphasized that while contamination in one modest stream or ditch like Prendergast’s may seem inconsequential, policymakers must consider the cumulative effect of that pollution, which could flow throughout the wider watershed—in this case part of the Colorado River Basin that supplies Colorado, six other states and Mexico.

Federally protected waters have a detailed permit process under the Clean Water Act that evaluates the potential impact on endangered species for any project that discharges dredged or fill material into waters of the United States. A project that even scarcely touches these waters could be fair game, from dams to highways. If ephemeral bodies of water are no longer under federal jurisdiction, then a permit is no longer needed for them. That would leave developers on their own to make sure that their project won’t violate the Endangered Species Act.

Although some developers might celebrate averting this permitting thicket, non-compliance with the Endangered Species Act could come back to bite them. Civil penalties can result in up to $25,000 of fines per violation.

“It should be of concern to the applicants because what it’s doing is it places the liability on them,” said Julia Fonseca, environmental program manager for Pima County, Ariz., where cottonwood-willow forests reside along ephemeral waterways and provide critical habitat for desert species.

Fonseca, who also worked on the 2008 EPA study, thinks that in addition to its implications for Endangered Species Act compliance, the Trump administration’s water-rule change leaves states, including Arizona, “in regulatory limbo as to where the jurisdiction of CWA begins and ends.” Like Colorado, there’s no statewide program in Arizona for regulating the discharge of pollutants like dredge or fill material into streams; the state government relies on the Clean Water Act for guidance. Taking ephemeral streams out from under that federal guidance leaves the state without a road map for regulating and protecting such waterways.

“The Clean Water Act was always intended to be a national sort of floor for state programs,” said Fonseca, noting that in fact states could, and often did, exceed the water-quality standards. “With this change, instead of the Clean Water Act being the national floor for water quality, it’s the ceiling.”

The research done by Fonseca, Semmens and their colleagues disputed the assumption of the Trump administration’s rule that ephemeral streams largely exist in isolation. While these waterways are often located at headwaters that directly flow into perennial rivers at the surface, their channels are also key spots for groundwater recharge. Their streambeds are more porous, allowing water to infiltrate the aquifer below more rapidly than perennial streams. Any contamination in these channels could make its way into aquifers or surface waters that will later be tapped for human use. In Arizona, for example, groundwater accounts for 40% of the state’s water supply.

As November elections draw near, the fate of the Trump administration’s rollback of the Obama water rule is up in the air. If Democratic candidate Joe Biden is elected as president, then his administration could attempt to reverse course and resurrect the Clean Water Rule, or a close proximate, according to Biden’s campaign.

Longform Story CSS Block

Jenna Sampson is a freelance environmental journalist and contributor to The Water Desk. You can find her on Twitter @jennadawn.

Julia Medeiros writes articles and manages social media for The Water Desk. You can contact her at juliacmedeiros.wordpress.com

Summer Taylor is a freelance photographer and videographer. You can contact her at summertaylorvisuals.com

Interactive Map