Water Desk Grantee Publication

This story was supported by the Water Desk’s grants program.

Etched into the face of a red sandstone cliff in the arid highlands of northwestern New Mexico is an unlikely image: a delicately outlined fish. Dozens of petroglyphs surround it, carved centuries ago by the ancestors of the pueblo tribes who still live in the region. They depict antelopes, humans, supernatural beings, spirals and other figures. The antelope and human forms don’t seem out of place, but a fish, here on a dry scrabbly plateau incised with ravines?

“What this tells me is there was once a helluva lot more water here,” says Jim Enote, a 63-year-old Zuni farmer and tribal historian whose forebears were cultivating this land long before the first Europeans arrived on the continent. “Some of these petroglyphs are 1,500 years old. They’re a testament to how long we’ve been here.”

Tribal lore and the archaeological record indicate a very long presence of a people who developed unique agricultural methods and bred crops exquisitely adapted to a land perpetually threatened by drought. The ancient civilization from which the Zuni and other pueblo tribes of the Southwest descend left behind multistory dwellings, networks of roads, astronomical markers, tools for grinding corn and bins for storing it.

Aside from enigmatic petroglyphs, the ancestral puebloans left no written record of what must have been an epic history. Many of the most spectacular sites—like the 600 cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde in southern Colorado, or the enormous pueblo complex of Chaco Canyon in northern New Mexico—were abruptly abandoned about 900 years ago. Tree-rings and other data suggest that a prolonged drought, which may have dragged on for 50 lethal years, caused widespread societal collapse.

That history has become disturbingly relevant. For the last 20 years an extreme drought has gripped much of the Southwest. Maps generated by the National Drought Information System invariably show the Zuni homeland to be one of the most parched sections of the country. The tribe has already declared three drought emergencies in the last 15 years, prompting the construction of new water hauling sites and restrictions on the community’s water use. The drought’s impact on wildlife has cost the tribe lost revenue from the sale of hunting and fishing permits. Meanwhile, farmers and ranchers face increased predation on livestock and more crops lost to elk and other wild herbivores desperately seeking forage.

As climate change takes hold, it’s likely that states of emergency will become the new norm, with droughts even more devastating than those that toppled the Southwest’s pre-Columbian cultures. One climate scientist has warned that “the 21st-century projections make the megadroughts [of the past] seem like quaint walks through the Garden of Eden.”

What impact will a changing climate and perpetual drought have on the 11,000 residents of the Zuni reservation? The tribe has weathered a litany of existential challenges over the centuries, from the intrusion of the first conquistadors in 1540 to the arrival of Anglo settlers in the 19th century. And still older tribulations are hinted at in the petroglyphs. Kneeling by the sandstone rock face, Enote points to an engraved spiral, a symbol, he says, of the migrations the Zuni made across the Southwest before settling in their present home here on a 720-square-mile reservation. Some of those ancient odysseys must have been driven by the catastrophic droughts of the past, with entire peoples on the move in search of land that could sustain them. Now the same threat, horribly amplified, looms over their descendants—indeed, over all of us. “The big question for me,” says Enote, “depending on how extreme climate change will be, is can we adapt?”

Five years ago a team of scientists from Cornell, Columbia, and NASA published a paper with an unsettling conclusion: if greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase at the current rate, the risk of a “megadrought” hitting the Southwest—one that lasts for 35 years or more—will exceed 80 percent by the end of the century. Since global carbon emissions hit an all-time high last year, the odds continue to mount in favor of a megadrought worse than the civilization-killer of a thousand years ago. Last week, scientists from NOAA, NASA, and four universities reported that the megadrought may already be underway. It’s a sobering prospect, given that that the ancient megadrought outstripped anything in the historical record.

“Things like the Dust Bowl or the recent California droughts or the 1950s drought in Texas, as big and as bad as they were, they don’t compare with some of the worst events that we see going back a thousand years,” says Ben Cook, a climate scientist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York and the lead author of the 2016 study. “We know there were big droughts in the past that eclipse any of our contemporary experiences. There are very few places that have experienced megadroughts. I can’t think of any other region, at least in recent Earth history, that has ever experienced 20- to 50-year droughts [like the ones] that we have documented in the Southwest.”

As global temperatures continue to rise in the decades ahead, evaporation in the world’s arid areas will climb in lockstep, and precipitation will decrease, trends now underway. “When we’re looking at climate change impacts, they scale with the warming,” says Cook. “The more warming that happens, the worse these events—like droughts, floods and extreme precipitation—are likely to be. It’s going to be a combination of lack of water and these hot temperatures that are really going to make these events different from those of the past. None of this is inevitable. But the science is clear: these are the sort of events that are likely to get more severe and intense in a warmer world.”

From the top of Black Rock Dam on the Zuni reservation that drier world isn’t hard to imagine—it’s already here. Built in 1908, as part of an effort to modernize traditional Zuni agriculture, the 80-foot-high dam was designed to hold 15,000 acre-feet of water—enough to cover 15,000 acres to a depth of one foot. But apart from a small shallow pool from some rare recent rain, there’s no water in sight. Stands of juniper, cottonwood, and sage grow on land that should be under water.

“I can’t remember the last time water was released from Black Rock Dam,” says Kirk Bemis, the Zuni tribe’s hydrologist, as he looks out at the waterless expanse. “At least 15 years ago. This is the safest, most up-to-date dam we have and it’s in our most populated farming district. You just need to add water!”

Bemis, who is half Zuni on his mother’s side, once dreamed of being an astronaut. He got close, working as an engineer at NASA before returning to the reservation 25 years ago. Two of his uncles are priests in one of the tribe’s six ancient religious orders, each with its own elaborate rites and restricted membership. He seems comfortable in two worlds, one technical, one traditional. His efforts to bridge them can be challenging at times, especially when he raises the issue of climate change as something the tribe should prepare for.

“We have a cultural taboo about predicting bad things,” says Bemis. “Our religion is all about bringing precipitation here. Everything is about asking for the blessing of moisture from the ancestors and deities. If you tell the Zuni it will snow and rain less, you’re telling them that their prayers will be less effective.”

In any case, says Bemis, drought is nothing new here. “For us, climate change means more of the same.” After all, what lessons can the Zuni learn from a dominant culture with a dubious record of environmental stewardship? The construction of Black Rock Dam, for example, accelerated the decline of Zuni farming, and permanently changed the landscape.

For centuries, the Zuni, Hopi, and other pueblo tribes of the Southwest practiced a type of agriculture that enabled them to produce bumper crops of corn, beans, and vegetables in a region that receives about 12 inches of rain annually in good years—less than a quarter of the precipitation of a corn belt state like Ohio. Rather than planting and irrigating the same plots year after year, the Zuni rotated their fields, locating them near the bases of mesas to capture ephemeral runoff from seasonal storms. Remnants of small dams that channeled runoff water have been found at Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Casas Grandes, and other sites.

With runoff agriculture the Zuni thrived for centuries. When the gold-seeking Spanish explorer Francisco Vazquez de Coronado encountered them in the summer of 1540 he noted in a letter to his superiors that the Zuni “…are well-nurtured and conditioned…they eat the best cakes that ever I saw…” Runoff farming spread nutrients from the mesa tops out across the lowlands, and the channeling and slowing of storm flows reduced erosion. The numberless arroyos that now seem to be endemic, natural features of the Southwestern landscape may be a consequence of the abandonment of traditional farming practices.

“Traditionally corn farming was at the edge of a valley, close to mesas,” says Bemis. “Those fields couldn’t be used with modern irrigation because of the slope. So places in the valley that hadn’t ever been irrigated were [irrigated].”

Black Rock Dam, which had been a showcase irrigation project of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, started to fill with silt soon after its completion. Silt deposits from the intermittent flows of the Zuni River and its tributaries eventually cut the dam’s capacity from 15,000 acre-feet to 2,500. “In the late 1990s there was a $20 million project to fix Black Rock Dam,” says Bemis. “But since then there hasn’t been enough water to test these improvements. There hasn’t been water here for so long that some community leaders have proposed building a baseball field here. It shows you how soon people forget with drought conditions.”

Zuni agriculture had already been under pressure from the federal government even before the dam’s construction. With the Allotment Act of 1887, the United States attempted to integrate tribes into the mainstream by transferring what had been tribal commons to individual farmers.By allowing families to sell their plots, the act fragmented Indian lands. Within 20 years tribes all across the country lost nearly half their territory. “It was a way to break up the tribes by assigning plots to individuals,” says Bemis. “Traditionally farms were communally operated, not fenced off into land regarded as ‘mine.’ Here on Zuni there were only a few allotments, so we were lucky. But that started the decline of Zuni agriculture.”

Today the reservation comprises five agricultural districts, but only a handful of people in those districts are actually growing anything, says Bemis. The combination of drought, misguided federal policies, and economic pressures have decimated Zuni farming. In a community with a 70 percent unemployment rate, the risks and effort far outweigh the rewards.

“Most farming here is not commercial,’ says Bemis. “It’s for a little extra income or for personal use. If your field is far from your home, elk can come by and consume your entire summer’s work. In the old days farming was about survival. You didn’t have a choice. Now you can go to the store to buy corn. One of our dilemmas is how to revitalize farming.”

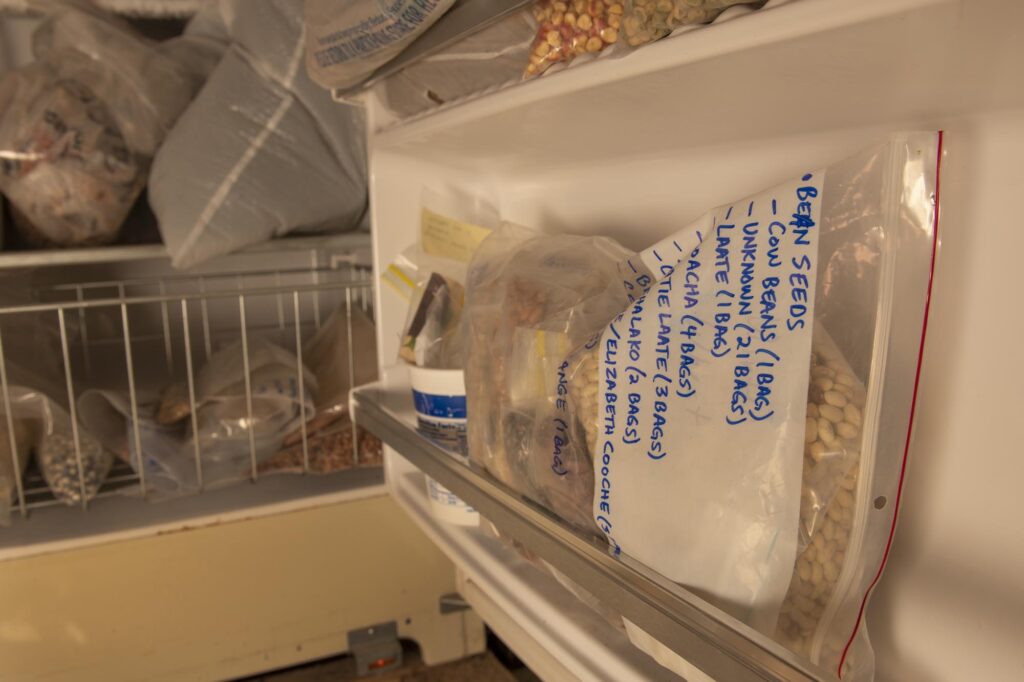

Some of the most sacred treasures of the Zuni people—precious links to their past and future—aren’t sequestered in religious shrines, or locked away in museums. They’re kept in a small one-story building that houses the Zuni Sustainable Agriculture Program, carefully tended by Daniel Bowannie, the 37-year-old technician and sole staff member of the project. The door of the boxy white refrigerator in Bowannie’s office is covered with his children’s doodles, so visitors might not immediately notice the piece of paper taped to the top of the fridge, which identifies it as the Zuni Community Seed Bank.

The refrigerator contains dozens of heirloom seed varieties—corn, melon, beans, and more—which have been collected since the program started in 1992. “Probably about 40 different families of seeds,” says Bowannie. “All seeds are sacred to us.” For the Zuni, agriculture itself is a religious practice, and locally grown seeds remain essential for many rituals. “There are two things we pray for: seeds and water,” says Darren Sanchez, who works for the tribe’s conservation program in an office next to Bowannie’s. “We can’t survive without them.”

The seeds in Bowannie’s refrigerator are unique, the product of countless generations of breeding drought-tolerant varieties by pueblo farmers. The corn, for example, can send roots 20 feet into the soil in search of water, and though the plants may grow only 3 or 4 feet high, they produce many ears. Bowannie started adding to the collection shortly after he was hired in 2003 to run the program. “I wanted to be a smoke jumper,” he says, “but my grandparents pulled me back to traditional life.”

He managed to get a few seeds from elderly Zuni farmers, but his most valuable source turned out to be another ancient community. “For heirloom seeds I reached out to my relatives, the Hopi.” The Hopi, whose reservation lies in northeastern Arizona, also see agriculture as a spiritual practice, and runoff farming is still a living tradition there. In 2008, Bowannie described his plans to provide heirloom seeds for the Zuni community to about 20 elders gathered at the Hopi Department of Natural Resources building. “The elders told me, ‘We don’t care about money,’” Bowannie recalls. “’These aren’t Hopi seeds—they’re Zuni seeds. A long time ago you gave us seeds.” At some point it in the past, it seems, the Zuni had helped the Hopi during a time of need. Now, perhaps centuries later, the Hopi were returning the favor. Though they did ask for one thing in return: salt from a sacred lake.

Zuni Salt Lake, home of the Salt Mother Deity, lies about 60 miles south of the reservation. During the dry season, most of the shallow lake evaporates, and the salt left on the dry lake bed has been gathered by pilgrims since before the collapse of the ancient pueblo civilizations. The Zuni control access to the lake, and even among the Zuni only the men are allowed to harvest salt. Since Bowannie himself had never gone before, he asked a coworker to collect salt that he could exchange for the Hopi seeds. So one day in 2008 in a parking lot in the city of Gallup 40 miles north of the reservation, Bowannie traded 22 sandbags full of salt for some Hopi seeds.

If the Zuni ever manage to revitalize their agricultural traditions, the trove in Bowannie’s refrigerator will enable them to plant the seeds of their ancestors. For now, those seeds are used to grow corn for religious ceremonies, and to teach Zuni schoolchildren the rudiments of traditional gardening methods; they are also distributed to a few committed farmers. Bowannie recalls how he learned to plant his first waffle garden, a quintessential Zuni horticultural technique where vegetables are grown on a bed of soil divided into a grid of small squares with raised earthen sides a few inches high. The plants within each square would be carefully hand-watered, ladle by ladle.

“I asked an elder, ‘What is the secret of waffle gardens?’” says Bowannie. “She said, ‘You’re not ready to listen to my stories. Why am I going to give this to you? You haven’t earned it. It won’t be appreciated in your heart in the same way it is for me. Go and plant a garden. Then come back and talk to me.’ She wanted me to take the initiative. Then she would step in and help. I started a garden and that opened up a conversation.’”

All that accumulated agricultural wisdom expresses something much more fundamental about Zuni culture. Driving back from Black Rock Dam, Bemis mentions that scientists occasionally visit the reservation, seeking indigenous knowledge about dry-land farming. “When they come here and ask about our traditional practices, I really have to think,” says Bemis. “What practices do we really still do? No one uses digging sticks (for digging out tubers and roots) anymore! The one tool that has survived is the belief system: the prayers, the ceremonies, everything that goes with that. That is the number one thing that has survived, and it developed, I’m sure, as a response to climate and extremes. That was the foundation for everything, and that is what has allowed us to live here and survive for all these years in a harsh environment. Technologies come and go, but a belief system, that becomes a way of life. It stays and grows. That’s the most important thing that has survived.”

Not all Zuni have relinquished the old farming ways. Late on a bright November day Jim Enote shows a pair of visitors a cornfield he has tended for as long as he can remember. It’s fallow now; the harvest of multicolored ears of corn is safely stored in bins at his home, along with beans, chiles, squash and more. On the horizon to the west of his field, bathed in golden light, stand the ruins of Hawikku, the pueblo where the Zuni were living when the first conquistadors arrived, vainly searching for mythical cities of gold. Maybe they too saw sunlight one late afternoon, gleaming on whitewashed pueblo walls.

“I’ve been planting for 62 years,” says Enote. “When I was in a cradleboard, my aunties and grandmother would put seeds in my hand.” Enote, tall and silver-haired, has been planting seeds ever since, and shares his knowledge on many fronts. Most recently he has started a non-profit organization, the Colorado Plateau Foundation, which aims to promote sustainable agriculture and protect native lands and languages.

“Our culture was built around growing food,” he says. “Planting food connects you to all these things: the soil, the weather, the creatures that share this world with us, and the moon and the sun. When you put your hands in the soil, you feel how cold or how warm or how dry or how wet it is. It connects you to all these things we pray for. We’re at a tipping point. People will either make the decision to grow traditional crops in the traditional manner or they won’t. I think that would be a tragedy. I always tell the kids, just plant something in the ground and take care of it.”

You made it this far so we know you appreciate our work. FERN is a nonprofit and relies on the generosity of our readers so that we can continue producing incisive reporting like this story. Please consider making a donation to support our work. Thank you.

This article was first published by The Weather Channel. It may not be reproduced without express permission from FERN. If you are interested in republishing or reposting this article, please contact info@thefern.org.

Tim Folger writes about science and environmental issues for a number of national publications. He lives in northwestern New Mexico, not far from Zuni pueblo.

Photojournalist Bill Hatcher has photographed exploration, science and conservation around the world for over 30 years. Working for a variety of clients including National Geographic, Smithsonian, Outside Magazine and Outdoor Photographer, Bill’s images have received several awards, including those from Communication Arts, ARCHIVE and the Emmy Awards. Bill currently lives in Tucson, Arizona, and Dolores, Colorado. His most recent projects have been focused on the Borderlands of Arizona and Mexico and the Four Corners regions of the American Southwest.

This story was produced by The Weather Channel in partnership with the Food & Environmental Reporting Network. Reporting was supported by The Water Desk at the Center for Environmental Journalism, University of Colorado Boulder.

Longform Story CSS Block

Longform Story CSS Block