By Jerd Smith

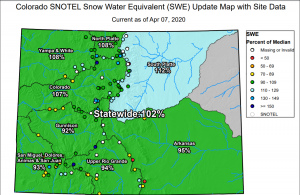

Colorado mountain snows, the primary source of the state’s annual water supplies, hit 102 percent of average this week, a bit of good news that hydrologists and forecasters were glad to embrace.

“If folks are looking for something to be grateful for now, a healthy water situation is on the list,” said Peter Goble, climate specialist at Colorado State University’s Colorado Climate Center.

Snowpack is measured across the state’s eight primary river basins. The highest numbers this week were found in the South Platte River Basin, home to such major cities as Denver, Boulder and Fort Collins. Here snowpack measured 112 percent of average.

The lowest readings occurred in southwestern Colorado, where snowpack in the San Miguel/Dolores Basin measured just 93 percent of average, according to the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) snow survey.

Colorado’s reservoirs are also showing strength, with most projected to fill. Storage levels this month were registering at 107 percent of average statewide.

Thanks to the pandemic, the teams of hydrologists who normally climb high into the mountains to manually measure the snow each month were tied to their desks, observing the stay-at-home order and relying on the state’s remote SNOTEL sites for data. Under normal circumstances, NRCS staff combine remote sensing data and field data to compile the critical monthly snow reports.

But Karl Wetlaufer, who leads the NRCS snow survey effort in Colorado, said his team was able to use additional modeling to help fill in the data gaps this month, and they’re working on a contingency plan for compiling their last major readings May 1.

“The mountain communities were among the hardest hit [by COVID-19], so we discontinued the manual measurements for April 1 to minimize any potential spread,” he said.

While snowpack and reservoirs are strong, forecasts for streamflows, which build as melting snow reaches streams, are expected to be below normal across southwestern and southeastern parts of the state.

Snowmelt that normally would reach the streams in a healthy water year is likely to be captured by soils that have dried out, thanks to ultra-dry weather late last summer and into the fall.

“We’re a bit worried about southeastern Colorado. Dryland farm operators are struggling because it was dry last fall and they had a dry winter,” Goble said, meaning there was little moisture to help crops such as winter wheat, produced without supplemental irrigation, grow.

In the Rio Grande River Basin, where snowpack is registering at 94 percent of average, farmers are hoping they will see more moisture in the spring to compensate for the below-average snowpack and dry soils.

“Streamflows are forecast at 70 percent of normal,” said Cleave Simpson, manager of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District in Alamosa. “It’s still better than 2018, but it’s not great.”

The broader Colorado River Basin, which stretches beyond state lines all the way into Mexico, is also expected to see below-normal streamflows, impacting major regional storage reservoirs, such as Blue Mesa in Colorado and Lake Powell in Utah and Arizona, which are likely to receive just 50 percent to 70 percent of normal inflows, respectively.

As a result, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the April-July inflow into Lake Powell is forecast to be just 78 percent of average. This is a critical number because it determines how Lake Powell will be managed this year, including how much water will be released to Arizona, California and Nevada and when.

Looking ahead, Goble said, forecasts indicate a slightly higher chance of drier, rather than wetter, weather from April through June, making it unlikely that those regions which are already beginning to dry out will see much relief.

Thanks to the lingering dry conditions, more than half of Colorado remains in drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, with portions of the southeastern and southwestern parts of the state classified as being in severe drought.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org

This story originally appeared on Fresh Water News on April 8, 2020.