By Tim Cooney

On the afternoon of Aug. 23, 1895, Frank Klangel felt the urge and went out to the privy behind his uncle’s saloon, Adam’s Place, on Cooper Avenue between Hunter and Galena in downtown Aspen. As the angled sun over West Aspen Mountain (today’s Shadow Mountain) streamed through the open door into the usually dark place, Klangel looked down into the vault hole to commence business. There he saw a man’s feet clad in heavy shoes sticking up out of the muck.

Saloon owner Adam Klangel, jailer Hudner, police Capt. Williamson and coroner Hughes “inaugurated measures to get the man’s body out of the fearful receptacle,” the Aspen Times reported the next day. “All his body was buried except the pedal appendages.”

With the building overturned, the coroner climbed down the wood cribbing of the vault and secured a rope around the dead man’s feet. A number of men assisted in raising the corpse, which was so covered as to be unidentifiable.

They spent an hour hosing him — laid out in the street — and cutting off his clothes before the coroner could examine the body. Word spread and a crowd gathered “to witness one of the most despicable sights ever brought to mortal vision,” one that “tested the endurance of the strongest constitutions,” the Times said.

In the crowd was a member of the deceased’s family, who at a certain point identified the body of Irishman Dominik Crosson, a pumpman for the Schiller Mine on Aspen Mountain (off today’s Schiller Road ski trail). Crosson had left his home on Juan Street for work at 7 a.m. the day before, but “later in the forenoon was seen among the Cooper Avenue resorts.”

Coroner Hughes noted bruises on Crosson’s face, but no wounds indicated foul play. Hughes concluded that an inebriated Crosson stumbled on the upright board that served as a seat and fell into the “sufficiently large aperture where he entered the death trap.” The coroner surmised he had been upside down in the viscous night soil for the past 24 hours.

Vault mining

Make no mistake that the good-old days in earliest Aspen were better than now. The Times editorialized on March 22, 1890, that Aspenites “were careless to the preservation of their own health,” due to the estimated 2,500 privy vaults and cesspools in the city proper that had been accumulating filth since 1880.

On the heels of silver mining prosperity, early townspeople simply threw dirt on top of a full vault and dug another. Newspapers reported open cesspools under wooden sidewalks around town. Accumulation, seepage and odors had to be addressed because they affected health and clean drinking water.

Add to that the spring rains and snowmelt that churned an unimaginable mud season, where town commerce and mule-drawn delivery became a challenge. The March 27, 1893, edition of the Aspen Daily Chronicle warned, “West Main Street is not navigable for mud scows drawing over four feet of water.”

Between 1879 and through the early 1900s in the mining camp, polluting was a de facto industrial right. Everything from mining waste, sewage, slaughter offal, city dump runoff and sawdust drained into the Roaring Fork River. With cholera outbreaks around the world and medicine finally connecting the circular route of disease from sewage to table, Aspen doctors warned of the need to avoid a city pestilence.

Although mortality in Aspen due to dysentery and idiopathic fevers was often mentioned in the newspapers, and with local cemeteries evidencing many young deaths, one clip in the Times noted that the “little son of Mr. and Mrs. Bert Watts nearly died of cholera infantum.”

In 1890, the Times reported that Aspen officials had directed W.J. Connors — who was the “city scavenger,” an official position since the mid-1880s charged with cleaning and disinfecting alleys with lime and hauling animal carcasses, slop, night soil and more to the city dumping grounds — to clean out the old vaults, at $15 to $240 per vault. City scavengers quit often, but the higher-paying job came with city-backed “enforcement and emoluments.”

The vault-cleaning “work is done in the silence of night all winter long,” and once opened, “for a three block radius it is impossible to breathe. … The labor is severe and the men use strong disinfectants and take extra care of their health in the vitiated atmosphere,” the Times wrote. Connors’ crew, utilizing horse teams, dug out 450 vaults that winter, some as deep as 40 feet.

Lazy dumpers

Before 1889, the city dumping grounds were in the Riverside Addition, the Times noted on April 28, 1888, a poorer neighborhood just over today’s Roaring Fork River bridge toward the North Star Nature Preserve, where many Irish and English miners lived and a lot cost $50. There the city regularly took bids to burn animal carcasses.

On March 30, 1889, the Rocky Mountain Sun (RMS) wrote that the city dump had relocated to a 10-acre parcel overlooking Maroon Creek (near today’s Aspen High football field), where it remained until the 1960s. The newspapers between 1890 and as late as 1917 cited noxious accumulations and lazy dumpers tossing carcasses and putrid refuse along the road to the dump. Accounts said festive trips to Maroon Bells were a gauntlet-like challenge and the air in the town’s West End sported the odor.

In Glenwood Springs (originally called Fort Defiance), where the Roaring Fork T-boned the Grand River, the Times reported on Oct. 5, 1888, that the mayor and the entire board of trustees were arrested for telling their town scavenger Mike Tierney to dump offal into the Grand, in violation of a state statute concerning pollution of a running stream.

In 1897, the July 3 edition of the RMS headlined a story “Fishing vs Mining,” wherein state game warden Swan served notice to Aspen’s Smuggler Concentrator to “cease putting tailings into the Roaring Fork and so into the Grand,” that the “mine water is poisonous and destroying the fish.”

The newspaper countered that the opaque water “preserved trout from the persistent whipping by town anglers,” that Swan’s attempts are “a piece of bumbledom” and “the biggest and gamest trout is not worth the contents of a workingman’s dinner pail.” The paper argued he would close down Aspen mines, put thousands out of work and bankrupt shareholders. “With mines, it is impossible to stop putting runoff in streams. Swan must be taught this and his officiousness curbed.”

River bears it away

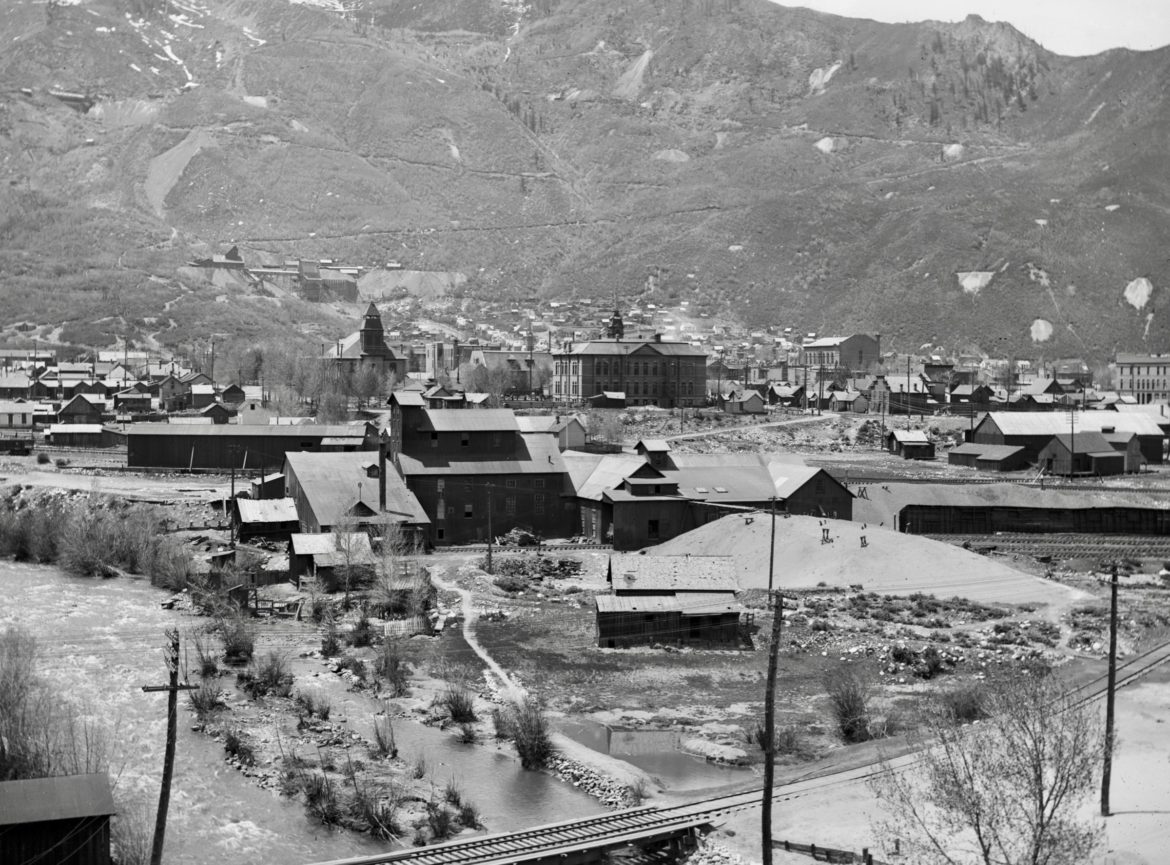

In fact, Aspen was an industrial Victorian city with the unhygienic conditions of Dickensian London. During the camp’s mining boom between the mid-1880s and early 1890s, the population of between 12,000 and 14,000 peaked in 1893.

As has been the case since civilization, rivers have served as disposals; however, the Roaring Fork had an extra advantage in settlement days, before later water diversion, when it unleashed a good month-long torrent during spring runoff that scrubbed mining and foul sediment out of the deeper riverine pools. This flushed everything downstream to Glenwood and beyond.

But this hard-working act of nature was diminished when Eastern Slope water diversion in the early 1930s fractioned the Roaring Fork’s runoff. Accounts say the Roaring Fork got its name before diversion because the daily roar was so loud around town that people had to yell.

These days, the norm is mostly a quiet meandering, and the observant might notice during the low-water season of August that the once-natural-colored rocks along the Rio Grande Trail on down are permanently stained black from past ore-processing waste.

Primary sources

These observations and more — found in the Aspen Historical Society’s archives in a 1976 firsthand, written account by Bede Harris, who was born in Aspen in 1884 — say that mine dross stained the river a lead color from the Neale Street Bridge (today’s No Problem Bridge) down, leaving a blue, black and brown hue on the rocks and sand bars, even past Basalt.

Difficult Creek and upper Roaring Fork rocks were also stained by early 1880s runoff from upstream gold mining in the town of Independence, on Independence Pass. An RMS article titled “Our Drinking Water,” published Oct. 9, 1886, described concentrate from two wood-fueled stamp mills there as discoloring the “almost perfect translucent (water) to a yellow ochre, with the consistency of new made cheese,” lacing it with “undetectable quicksilver” (mercury) from the stamp plates.

Before that mix reached Aspen, the story said, the water cleared itself. Yet Andy McFarlane’s early 1880s sawmill, just east of town, and timber work in McFarlane Gulch, above today’s Difficult Campground (see “Hope delivers Pandora’s Box,” aspenjournalism.org), added sawdust to the water. Other sawmills populated Castle, Maroon and Hunter creeks. The sawyer’s trick then was to run a canal under the saw blade that zigzagged back to the creek.

A detailed 1896 map of town by W.C. Willits, on file at the historical society, shows the lineup of Aspen industry draining waste into the Roaring Fork then: the Aspen Sampling works near today’s Gant condos; the Smuggler Concentrator (which Harris called the “lead mill”), near where the Eagles Club now stands; the Mellor Foundry in today’s Mill Street Plaza area; and Sander’s Brewery in the Pitkin Green locale. The RMS reported in 1885 that Aspen consumed 120 kegs of beer per day in winter and 160 in summer.

On Castle Creek, just above its intersection with the Roaring Fork in today’s Holden/Marolt grounds, the massive Holden Lixiviation Plant, the Union Smelting Company and the Aspen Smelting Company (a.k.a. Texas Smelter) sent their discard downriver as well.

This became worse, Harris wrote, after 1900 and through 1917 when mining-populist David Hyman massively dewatered and reopened the deeper levels of the Smuggler, Free Silver, and Mollie Gibson in hopes of a mining renaissance after the economic crash of 1893. (See “Dewatering Smuggler Mountain mines,” aspenjournalism.org.)

Harris mourned the loss of in-town trout fishing during Hyman’s mining revival and, after water diversion, the disappearance of water-skipper bugs, pollywogs, frogs, muskrats and the delightful water ouzel songbird that dips its head as it sings and dives under the current for larvae, before resurfacing and resuming its same tune. Gone too, he wrote, were the many toads about town that came out after summer cloudbursts.

As we know now, it all connects. But in Aspen’s short history in the scheme of things, how the early settlers first managed the abundant clean water from the mountains deserves a closer look.

Ute Avenue vanguard

When a handful of prospectors and Aspen pioneers first came over “Hunter Pass” (Independence) from Leadville in 1879, they dipped their tin cups into creeks without a thought of pollution or giardia. They camped by the clear, pooling waters of “Ute Spring,” which a rudimentary 1881 Aspen map at the Aspen Historical Society places between the soon-to-come Argentum Juniata and lower Durant mines, where today’s lower Aspen Alps abuts Aspen Mountain Road.

That map shows the Ute Spring streaming down a pastoral Original Street to Hunter Street, across today’s Rio Grande field and into the Roaring Fork near the John Denver Sanctuary. This runnel was Aspen’s first water supply.

Accordingly, original settlers built their cabins with access to the Ute Spring along Ute Avenue, the first official “street” in Aspen, an Aspen Times column on Feb. 21, 1886, recounted. Others erected tent dwellings and businesses along the spring’s flow down to the Roaring Fork.

As town boomed with silver strikes on Aspen and Smuggler mountains in the 1880s, water-supply routes for irrigation and general use became a priority for the camp.

Setting the stage prior to that, the robust B. Clark Wheeler (not to be confused with Jerome B. Wheeler of Opera House and Jerome Hotel fame) snowshoed over Independence Pass during the first winter of 1879-80 and resurveyed the nascent town of “Ute City,” which had already been laid out by the first wave of “’79-er pioneers.” After many had decamped for the first winter because of the rumor of a possible Ute Indian invasion, Wheeler registered his new plat in Leadville and renamed the town Aspen.

Some resented Wheeler, believing he had “claim-jumped” the town from the first settlers. On top of that, he declared ownership-by-discovery of the Ute Spring and set to managing it, reinforcing the ever-filling pool and installing spouts to fill barrels.

Then Wheeler claimed the rudimentary west-flowing “town ditch” first cut from the spring along the bottom of Aspen Mountain, which supplied water near Mill Street and Durant Avenue, where the Clarendon, Aspen’s first hotel, opened in 1881. Personal ditches connected to the town ditch, too. The first settlers down Ute Avenue had already built an east-flowing ditch from the spring to service them.

That same year, Wheeler started the Aspen Times, the first newspaper in town, which reported on April 23 that kids played in the ditches and dammed them, causing flooding, and reported on May 6 that the town trustees approved an ordinance: “No dead animals or brute or foul or nauseous substance” could be disposed of in the water ditches.

Of course, water flowing through uncovered ditches free to horses, burros, loose pigs and jacks became turbid. In 1882, a follow-up ordinance cracked down on sawdust disposal in the ditches and, later, in the Roaring Fork. Remarkably, some still took drinking water from the ditches.

Water monopoly

Initially, Wheeler let water flow gratis through the town ditch and original Ute runoff. But with his improvements, he aimed to profit. Entrepreneurial “watermen” brokered the clean Ute Spring water about town from him, delivering “table water” in barrels on carts, dubbed “Donkey Hydrants” by the Times.

One waterman said he would “rather trade with 10 men than one woman,” because women bargained too well. The waterman added: “Her weakness is her weapon.” Another said it “cost the Christian Church $4.50 every time a batch of sinners is baptized.”

Soon, controversy brewed, because many believed that nobody owned the spring water. A letter in the Times on Aug. 30, 1881, said “the great Ute Spring in its quiet beauty pouring forth its crystal flood … was put there by the great creator for all to use.”

Afraid that the town’s water supply might become unaffordable if Wheeler monopolized, Mayor Tanfield and a public interest of townspeople incorporated the Aspen Irrigation and Ditch Company (AIDC), the May 5, 1882, edition of the Times reported. They dug the first ditch from the Roaring Fork at the end of “Waters Avenue,” connecting with the original town ditch along the bottom of Aspen Mountain, which then commingled with the Ute Spring water Wheeler claimed as his.

That AIDC ditch snaked from Waters Avenue onto Ute Avenue — the original course of which the 1896 Willits map infers. The previously cited newspaper accounts indicate that the “Wheeler Ditch” trail along the Roaring Fork just northeast of today’s Ute Avenue is a misnomer and should actually be named the AIDC Ditch.

Stock in the town’s AIDC cost $5 per share. A day’s work digging equaled one share. This defrayed the delivery cost of $1.50 per month to town lots for those who worked, while water came free to lots planted with trees. The AIDC expanded ditches throughout town, while many dug their own channels off these to their dwellings or businesses.

Wheeler schemes

In reaction to the formation of the citizens’ ditch company, Wheeler cooked up a Victorian leveraged-buyout scam. The May 7, 1882, edition of the RMS reported that he speciously offered the new AIDC board use of “his ditch” (the original town ditch along the bottom of Aspen Mountain) and the natural Ute Spring runoff ditch to the Roaring Fork in exchange for consideration.

He valued his labor and infrastructure at a bloated $75,000, offering that as stock value in a new company to be under his control. But the AIDC rejected his offer and trenched that first ditch from the Roaring Fork at the end of Waters Avenue, which connected via flume over Wheeler’s Ute Spring waterworks with the old town ditch he still claimed as his property.

Next, the City Council stepped in and granted right of way to the new AIDC ditch water, nullifying Wheeler’s claim to the town ditch, the May 20, 1882, edition of the Times reported. With that, Wheeler showed his true colors.

His own paper — the Times — proclaimed on Sept. 9, 1882, “Troubled Waters” and “Attempted subversion of the existing order of things relative to the Ute Spring by B. Clark Wheeler … the water rustler.”

Aspen women take charge

Enraged, Wheeler tore out the AIDC’s bypassing water flume over his Ute Spring operation to the town ditch. He then rerouted “his Ute Spring water” solely into the town ditch, disrupting the AIDC flow and posting a notice threatening legal prosecution if anyone interfered, while announcing he would build a locked shed over the Ute Spring. Personal threats against him and plans to burn that building became shrill.

When finally confronted at the spring, the Times said, Wheeler threatened further court action to prove his ownership of the spring, surrounding property and water rights. With that, a contingent of town women took charge and surrounded Wheeler. The Times quoted one as saying, “If the men couldn’t manage him, the women could.” Wheeler backed down, but his reputation for being a tricky dealer continued.

In reaction to the uprising, Wheeler formed the rival Aspen Ice and Water Company in 1882. The RMS reported on May 5, 1885, that there were two ditch companies competing, the AIDC and Wheeler’s. At some point after, AIDC quit using the disputed upper town ditch, prone to overflowing into structures below, and built a lower ditch down Durant from their Waters Avenue river tap.

With water flowing unobstructed into gardens and stock pens, table water delivery resurfaced as an issue. The RMS reported on August 15, 1885, that someone dynamited waterman “Swede Jacob Brown’s” water tank because he was selling water at 25 cents per barrel, while other water-cart owners fixed prices at three barrels for $1. Weeks before, someone put coal oil in Brown’s tank and removed two “burrs holding a wheel” on his cart.

Donkey-cart deliveries from the prized Ute Spring water continued until 1889, when the Sept. 28 edition of the RMS reported the end of Ute Spring as a major water source because mining above had diverted the flow.

Much later, mining magnate David Hyman, for whom Wheeler originally brokered Hyman’s initial 1880s Aspen mining claims, reflected circa 1920 on Wheeler in his autobiography, “Romance of a Mining Venture,” that Wheeler was “a man of wonderful energy, of great professions, but whose character I never admired and whose knowledge of mining matters was not at all equal to his profession.”

Kidney health

With town growth, the hustle and bustle of more traffic, trash accumulation on lots, the mud-manure, road-base mix of town streets and settling detritus into the ditches, the need for water beyond the murky ditches became an infrastructure necessity and plentiful, alternative water from Castle Creek and Hunter Creek came on line.

To this end, the Aspen Water Company, “organized by esteemed townsmen H.C. Cowenhoven and D.R.C. Brown secured the franchise to supply the city with water,” the Times reported on Jan. 2, 1886. A crew excavated ditches and laid the water mains about town by that March.

That water supply came by flume and ditch out of Castle Creek to a reservoir on the west side of Aspen Mountain just downstream of today’s Music School. A 1900 photo at the AHS locates that oblong reservoir and another on the opposite side of the creek above today’s hospital.

After earlier debate comparing “Hunter’s Creek” (now Hunter Creek) with Castle and Roaring Fork waters, the town physician — to whom the city paid $50 a month, according to the complete town ordinances published in the July 27, 1886, edition of the Times — weighed in favoring the mineral composition of Castle Creek for better kidney health.

Upscale leavings

By 1889, the city installed two major sewer drains. The first, called the “Wheeler sewer,” after the other Wheeler, Jerome B., who financed it in 1888, ran 8-inch pipe 1,800 feet down Mill Street from the two-story, first-class Clarendon Hotel, which dominated the southeast side of today’s Wagner Park.

Those upscale Mill Street leavings commingled with inflow from the nearly completed J.B. Wheeler Opera House/Bank building and his Hotel Jerome, dumping that raw sewage into the Roaring Fork river near today’s Mill Street Bridge. The Sept. 2, 1889, edition of the Times reported the cost at $2,500 ($70,000 today), including lateral pipes to some adjoining streets.

The second sewer, the larger 2,200-foot Galena Street project, started at the base of Aspen Mountain and drained mine-waste water, which helped flush the raw, lower Galena sewage via a dogleg across the Rio Grande railroad yards into the river near today’s John Denver Sanctuary. This drainage came online in 1889, the Nov. 11 edition of the Times reported, with an “18-inch tile pipe” eight feet down that serviced the business center of town, at a cost of $5,725.

On the other side of the river, on North Spring Street across from this ripe excrement port, another poor neighborhood of 57 miner shacks called “Oklahoma Flats” — largely abandoned after the 1893 silver crash — conveniently set their privies at the water’s edge and let the river do the flushing. In later years, the area became known for its colorful residents such as “Slops,” “Midnight Mary,” “Hoofy” Sandstrom and Pope Leo Roland.

Thoroughly modern

In contrast, the Times, in June 1889, bragged that “the city embraces the handsomest dwellings of any mountain town in Colorado … with fine lawns and gardens … and abundance of water furnished to all desiring by the excellent Castle Creek water company.”

Roll-riveted steel and lead water pipes supplied new and old buildings. Many outskirt privies and “modern septic tanks” remained, while groundwater was too deep for in-town wells.

That same year, the new Hunter Creek electric power plant completed a building (today’s former Aspen Art Museum off North Mill Street), which housed Pelton-wheeled water turbines, powered by an 876-foot-vertical water drop from the Hunter Creek reservoir above. The innovative, cupped paddle-wheel, invented by Lester Pelton — a one-time Sacramento River fish monger in the California goldfields — captured the impulse force of the incoming water with cutting-edge efficiency.

So notable was this fin-de-siècle accomplishment in Aspen, the first town west of the Mississippi with hydro-electricity, that water engineers from Japan traveled to Aspen — arriving by stagecoach in 1888 — to study the technology and duplicate it in Kyoto, where that plant still stands today.

As electricity demand increased, the city along with Cowenhoven and Brown built the Castle Creek power plant in 1892 under “State Bridge” (now Castle Creek Bridge) using the same flumes-to-turbine mechanics.

Soon, electric lights illuminated downtown, “reducing police patrols,” according to a local newspaper account, as homes, mines and businesses multiplied with electric technology into Aspen’s peak mining year of 1893. That same fateful year, the U.S. government subsidy of silver prices and a bank-leveraged economy with too many railroad loans collapsed in the “Crash of ’93.”

Water, sewers refined

Yet Aspen carried on. The 1896 Willits map confirms expanded routes of the city’s water and sewage systems. Victorian-modern plumbing routed pipes into euphemistic “water closets” in new Aspen homes, with a seated bowl below and a pull-chain flushing tank overhead. Nickel-plated faucets, porcelain sinks, marble counters with wood trim and wainscoting styled out an upscale West End Aspen bathroom then.

The map further details where Brown’s Aspen Water Company laid the Castle Creek water main down West Hopkins to First Street, attaching lateral delivery into the West End and south to the base of Aspen Mountain.

At the other end of town, a city-funded water main tapped into the relatively cleaner Roaring Fork at the end of East Cooper above the polluting mills. This supplied the downtown core and east end of town up to First Street, north to Lake Avenue area, and south to Durant and Ute avenues.

These two sources combined then with a water main from Hunter Creek, which Brown et al. had an interest in. All three sources in the 1890s fully charged ubiquitous fire hydrants about town and allayed fear of fires starting in the many wooden tinderbox buildings. A gala downtown inauguration of the system shot water from hydrant hoses about 180 feet up in the air, and a full-on water fight with hoses by competing fire brigades entertained a raucous crowd, fueled by free beer from Brown.

The dust settles

Although momentum ceased as silver prices settled lower, steadily producing mines such as the Durant, AJ, Smuggler and Midnight kept working at modified levels into the early part of the 20th century. While hope burned for a revival of silver mining, small operations leased idle mining properties and tried to eke out a living that way.

At the same time, small in-town businesses, ranching and no demand for real estate made Aspen an idyllic, little Western town enjoying the innocent normalcy of the era, before igniting again into the early ski period of the 1950s. Along the way, the city and county upgraded purified water delivery and sanitation infrastructure at a steady pace.

All but forgotten, the massive tunnel diversion of Aspen’s Independence Pass watershed to the Eastern Slope for agriculture and development — a major Western Slope resentment for many years, which some in Aspen in the 1930s thanked for employment — is another story.

Still, on a positive note in these current times of environmental warming, microplastic particles, Frankenstein chemicals and global atmospheric transport of pollution, nature ostensibly cleaned the Roaring Fork River of toxic sediments since the mining era. Yet, the permanently stained rocks in the river stand as a reminder of our continuing stewardship.

Tim Cooney is an Aspen-based freelance writer and former Aspen Mountain ski patroller. He investigates Aspen’s history for Aspen Journalism’s History Desk and does so in collaboration with the Aspen Daily News. The Daily News published this story on Sunday, Jan. 5, 2020.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism. The Water Desk is seeking additional funding to build and sustain the initiative. Click here to donate.