“Water journalism? What’s that?”

I’ve triggered this response from people on chairlifts, airplanes and other places I tend to meet strangers.

When folks ask what I do, I tell them I’m working on a water journalism initiative at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Unless the other person is a media professional or a water wonk, my statement is apt to draw a quizzical look.

Average citizens know about “political” journalism, “sports” journalism, “business” journalism and other sub-disciplines that sometimes warrant separate sections in newspapers, or even publications unto themselves. But water journalism isn’t as well known—at least not yet.

For folks who are initially confused about water journalism, it usually doesn’t take long for them to get the concept. They start to think about water pollution and episodes like the lead poisoning in Flint. They recall the many news stories they’ve seen or heard about extreme droughts and floods whipsawing places like California and Colorado in recent years.

Public opinion surveys show most people don’t know where their water comes from beyond a general notion that it’s some river, reservoir and/or well. All too many of us take water for granted, because at least for now in the United States, the vast majority of citizens—but certainly not all—have a water supply that is clean, reliable and relatively affordable.

But if you’re one of the unfortunate people in this country or elsewhere whose water supply isn’t safe and secure, the subject can be impossible to ignore and warrants as much attention as possible from journalists, politicians and others. Just in California, home to one of the greatest concentrations of wealth and economic activity on the planet, around 1 million people are exposed to unsafe drinking water; globally, billions of people lack access to safe drinking water, managed sanitation or basic handwashing facilities, according to the World Health Organization.

Non-human species also depend on water for their survival, but here at home and around the globe, we have utterly transformed aquatic and riparian habitat by damming, diverting, depleting, defiling and destroying streams, rivers and underground aquifers, not to mention heating up the planet and spreading invasive species all over the place.

More than ever, we need water journalism to not only explore and expose these complex problems but also explain potential solutions to the public and policymakers. Unfortunately, the demand for more and better water journalism is coming at a time when the media landscape has been rocked to its core by tectonic shifts in how people consume news and access information.

With journalists continuing to be laid off and entire publications still collapsing on a regular basis, The Water Desk is starting up at a pivotal moment for both the news industry and the water sector.

Shining a light on a murky field

When you think about how important water is to every person on Earth, devoting more news coverage to the decisions, policymakers and institutions responsible for our water resources seems like a journalistic no-brainer.

A central goal of water journalism is to shed light on this critical yet murky part of our world in order to expand public understanding of water issues so that individuals, businesses, governments and other entities can make better-informed decisions about the most precious of natural resources.

In essence, water journalists need to constantly remind their audience that they shouldn’t, in fact, take their water for granted. Actually, they should care deeply about where their water comes from, what’s in it, how it’s used, what it costs, where it goes, who’s calling the shots and how human demands for water are affecting nature.

Most of us, myself included, need a better grasp on a slippery concept: water is embedded in virtually every product we buy—from beer to tomatoes to jeans to phones to cars. In addition to our carbon footprints, we also have water footprints.

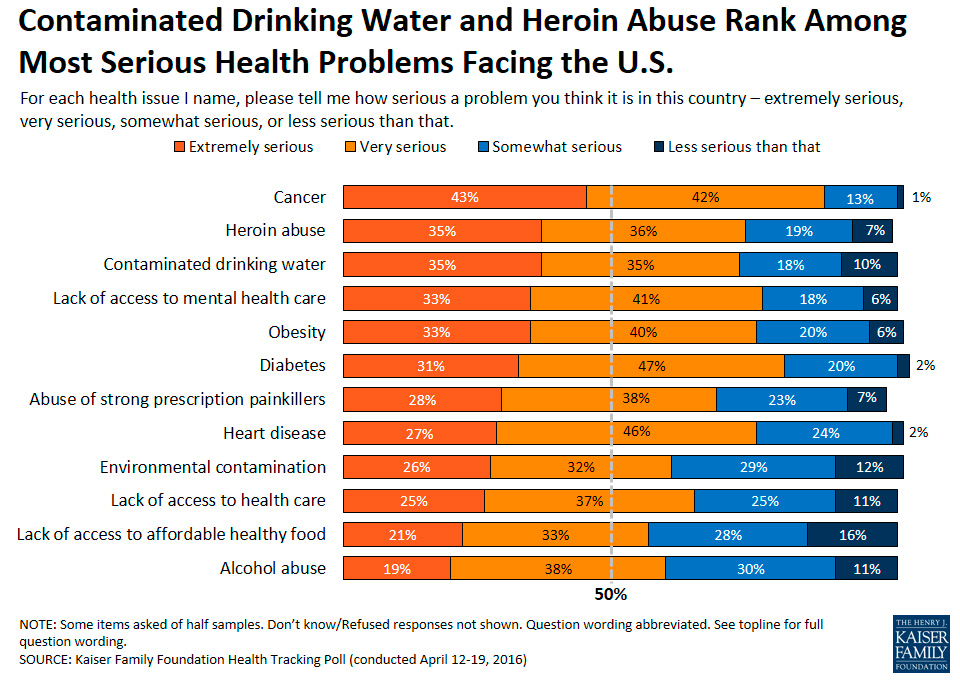

Saying you’re a water journalist may not seem like the best icebreaker, but if you start talking about water issues, it turns out that many people are keenly interested in the subject. The word “important” comes up constantly, and that’s borne out by a spate of public opinion polls conducted over a span of decades. These surveys have consistently shown that water is at the top of Americans’ environmental and health concerns.

For example, in an April 2016 poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation, Americans said contaminated water was as serious a health problem as heroin abuse (for more on water-related public opinion, please see my previous project, waterpolls.org).

Year after year, decade after decade, surveys conducted by Gallup have found that pollution of drinking water, rivers, streams and lakes rank much higher than other environmental concerns, such as climate change and the loss of biodiversity.

But it’s not just pollution that evokes worries. Especially in more arid places like the American West, where The Water Desk is focusing its work, the increasingly dubious supply of water also troubles the majority of residents. The Conservation in the West Poll, produced by Colorado College’s State of the Rockies Project, has found Westerners of all political stripes are concerned about low water levels in rivers and think our water supplies are getting less predictable.

As someone who has tried to explain water journalism and fundraise for it, I sometimes hear variants of the line that “water isn’t sexy.” Not so! It’s true that water issues can be as dry as dust. It’s easy to get bogged down in a quagmire of laws, hydrology, engineering and local politics.

But if you actually start covering water issues, as I did frequently as a newspaper reporter in California and Arizona from 1998 to 2006, you quickly realize that water does, in fact, animate your audience and inspire passionate reactions. Sitting through a five-hour hearing on sewer rates is unlikely to stimulate any erogenous zones, but nowadays I think water journalism is as exciting and important as any beat: we’re covering the lifeblood of every economy, ecosystem and community just as the entire hydrologic cycle of the planet is being amped up by climate change. Sounds pretty juicy to me.

Fresh water is scarce on the blue planet

Despite freshwater’s importance—and rarity—on Earth, water issues are typically ignored unless there’s an immediate crisis, such as a drought, flood or contamination episode. One of my favorite visual summaries of water issues is this cartoon from the National Drought Mitigation Center that depicts the “hydro-illogical cycle.”

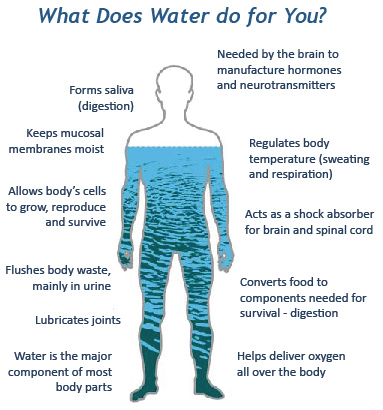

Here in the United States, it’s easy for most people to forget about water outside of a crisis. But if you’ve ever spent time in the developing world, suffered in a natural disaster, backpacked in the desert or lived in one of the disadvantaged communities where clean water is a luxury, you know there’s nothing more critical and visceral than water. In fact, up to 60% of our bodies consist of the stuff, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

You can live for weeks, even months or years, without adequate food, clothing or shelter. Deprived of water, you’re speeding toward a horrible death in a matter of days.

If there are any extraterrestrials spying on the Earth, I wouldn’t be surprised if they refer to our home as the “blue planet” or “water world” since about 71% of the surface is covered by the liquid. When astronomers and astrobiologists scan the heavens looking for possible life on other planets and their moons, they’re often looking for liquid water since it is, to the best of our knowledge, a prerequisite for life.

Our home planet, said to resemble a blue marble from space, is mostly covered with water, but the supply of freshwater that we can actually drink is minuscule by comparison. In the visualization below from the U.S. Geological Survey and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, the largest blue sphere shows all of the water on, inside and above the Earth, nearly all of it saltwater in the oceans. The volume of liquid freshwater is a tiny fraction of that: the second largest sphere over Kentucky is only 169.5 miles in diameter. And that tiny dot located around Atlanta you may not even be able to see? That sphere, just 35 miles across, represents all of the freshwater in the world’s rivers and lakes.

Our rivers and lakes are the most obvious and visible manifestation of our freshwater resources, but the graphic below shows why this supply is so scarce. Oceans account for 96.5% of all the water on Earth, and nearly all of the remaining water is either saline, locked up in glaciers and ice caps, or buried under ground, sometimes at depths that aren’t economical for pumping. Much of the freshwater that’s left over is ice and permafrost (at least for now).

Follow the water

Water is an essential, scarce commodity that we all need to survive. That sounds like another substance: money.

To find truth, journalists are supposed to “follow the money,” a famous line from the 1976 film All the President’s Men. (The phrase actually isn’t in Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s book about the Watergate investigation but was apparently uttered in a congressional hearing in 1974.)

“Follow the money” is sound advice because money is something that journalists, detectives, auditors and others seeking facts can at least try to count and track.

“Follow the water” is how one might summarize the goal of water journalism. Just as the “sports desk” at a newspaper covers the hometown teams and the “business desk” is for reporters and editors who track the economy, a “water desk” is supposed to follow this all-mighty substance as it flows throughout our economy and environment.

Today, it’s rare for general interest media outlets, such as newspapers, radio and TV, to dedicate an entire position to covering water. Many publications lump water coverage into the “environment” beat, which can also encompass a staggering number of other issues: climate, energy, wildlife, wildfires, development, public lands, air quality and more.

Defining water coverage as solely a sub-discipline of “environmental journalism” can pose some challenges. Don’t get me wrong: I think environmental issues are paramount in the water world. The Water Desk is based at the Center for Environmental Journalism, and I’m a card-carrying member of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

But water is more than just an “environmental” topic to be covered by “environmental journalists.” To be sure, the subject is immersed in green issues—climate change, biodiversity, pollution, growth and so on. But water stories can and should cover plenty of other terrain: it is a “business” and “economics” story because water it is crucial to everything from global supply chains to mountain-town economies, including the $1.4 trillion in annual economic output fueled by the Colorado River and its tributaries. It’s a “government” and “politics” story since public policies are so pivotal and many key decisions are made by government agencies or quasi-public entities.

Given that each of us depends on drinking and eating to survive, and most of us pay to use water, there are also “consumer,” “food” and “agriculture” dimensions to water journalism. Water is an “energy” story because there is such a strong nexus between the two sectors: fossil fuel and nuclear power plants require gobs of water while our waterworks demand tons of energy to treat, pump and move water.

Water journalism can also have a major “recreation” or “sports” component: think of all the publications that focus on leisure-time activities dependent on clean, reliable water, be it liquid or frozen. In many communities, the rivers, streams, lakes and snowpack are essential to not only the local economy but also the culture, so water generates plenty of stories for the “lifestyle” or “weekend” section of a publication.

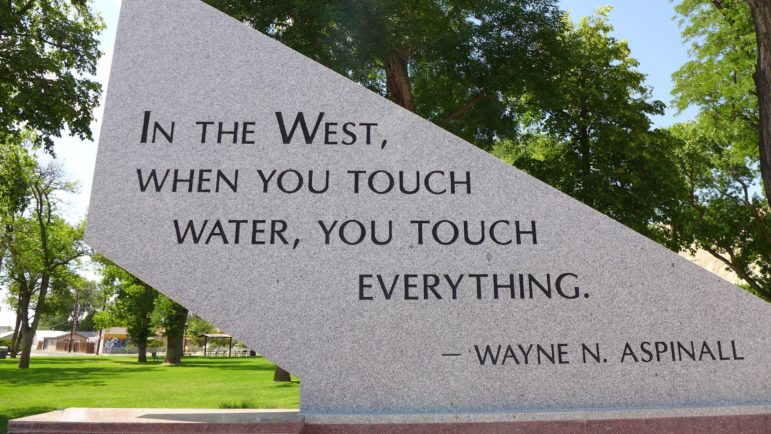

I’m usually not a fan of quote marks, but I’ve added them above because so often our journalism and other narratives are shoe-horned into such categories. I want water journalism to transcend these quotational buckets and cover all of the above to ensure that the public understands what everyone in the water field knows in their gut: water is intertwined with nearly everything and is absolutely integral to life. As 12-term Colorado Congressman Wayne Aspinall once said, “In the West, when you touch water, you touch everything.”

Defining our geographic scope

The Water Desk is all about water in its manifold forms and functions: source of life, basis for food, feedstock of the economy, not to mention fun stuff to fish, ski, and paddle.

One of the tricky yet fascinating aspects about covering water is that it’s constantly moving around and being reused downstream. Water is also the ultimate shape-shifter: the liquid can freeze solid, then sublimate into vapor, then condense back into liquid, then evaporate into the sky before precipitating—and on it goes around the globe. Fog, drop, flake, glacier, river, ocean, cloud—water transmogrifies through an amazing variety of forms ranging from the microscopic to the hemispheric.

While acknowledging the planetary nature of the hydrologic cycle, we have more humble and realistic ambitions for our work at The Water Desk. At least for starters, we’re focusing our coverage and grantmaking on just one part of North America.

Broadly speaking, The Water Desk is interested in a field that is often described as “Western water” or “water in the West.” As I discuss below, our focus is even a bit narrower since we are concentrating on the drier, Southwestern portion of the region, but suffice to say that among hydrologists, lawyers, policymakers, funders, publishers, conference planners and others, there is a field known as “Western water” that concerns management of the resource west of the 100th Meridian, the longitude that has traditionally marked the start of the more arid region where irrigation is necessary to support agriculture.

For this iconic demarcation, we can thank John Wesley Powell, the one-armed Civil War veteran and second director of the U.S. Geological Survey who explored the Green River and Colorado River in an epic expedition 150 years ago. The map below, from an 1891 USGS report, shows how Powell defined the arid region, which excludes the wetter areas of the Pacific Northwest and Northern California.

Despite the primitive technology of his time, Powell was onto something. The map below visualizes the 30-year average of precipitation across the United States from 1981 to 2010. I’ve superimposed the approximate location of the 100th Meridian, which really does demarcate a much drier portion of the nation, especially if you exclude the wetter Pacific Northwest.

The 100th Meridian (line added by author) has traditionally demarcated a much drier portion of the nation. Data source: PRISM Group, Oregon State University

But before you get too attached to the 100th Meridian, you should know that it has become obsolete due to climate change. Recent research has found that drier conditions have spread east by some 140 miles. It’s one of many climate zones around the world that are on the move in the Anthropocene, the modern epoch in which humans are transforming virtually every natural process on the planet.

In 2019, “beyond the 98th Meridian” might be the better definition for Western water issues. In fact, the issue of aridification—a long-term drying of the region due to changing temperatures and precipitation patterns—is fertile ground for some great journalism.

Although the West has the nation’s driest weather, one of the many awesome features about the region is that it simultaneously boasts the lowest- and highest-elevation terrain, as shown in the left map below. In fact, just 85 miles separates the top of Mount Whitney and the bottom of Death Valley, the highest and lowest spots in the 48 states. Not only that: the West is also home to some of nation’s hottest and coldest mean temperatures, as shown in the right map.

Focus on the Colorado River Basin

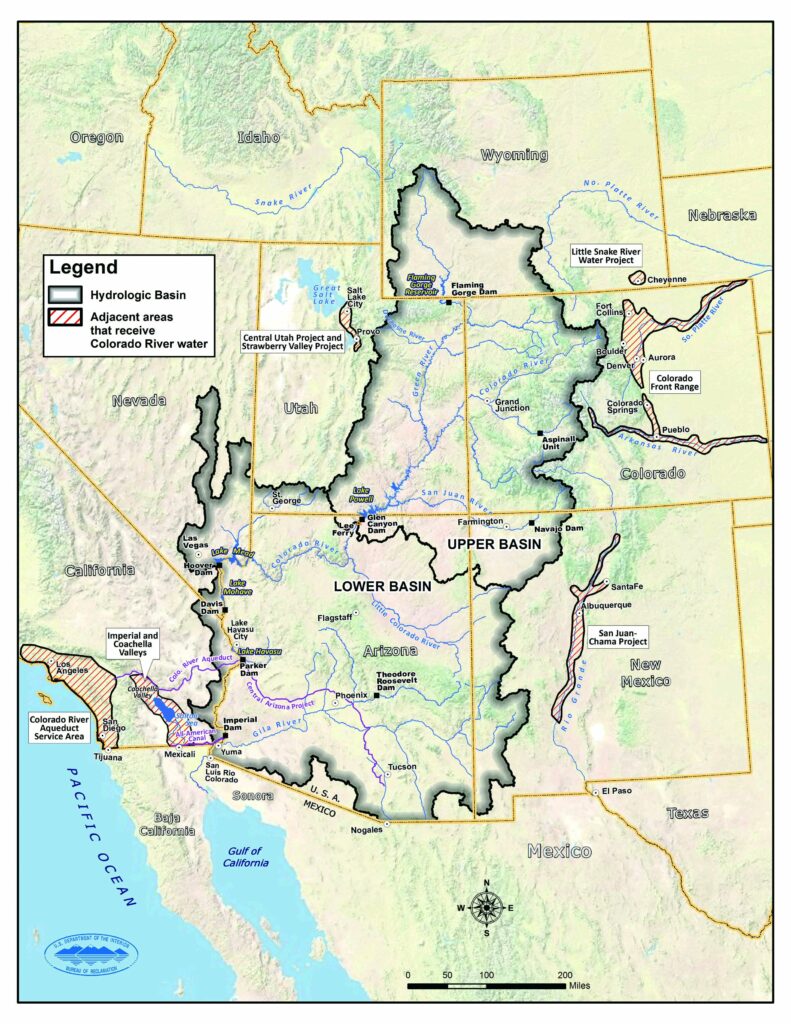

The Water Desk is concentrating on issues west of the ~98th Meridian, where the relative scarcity of freshwater and the region’s more recent development has yielded a legal landscape and physical infrastructure that’s distinct from the political and hydrologic regimes back East. Within this sprawling and diverse geography, we are focusing on a smaller region centered on the Colorado River Basin.

The emphasis on the Colorado River Basin and surrounding areas stems in part from the priorities of our initial funder, the Walton Family Foundation, which has a large grantmaking program in the region. The Water Desk maintains a strict editorial firewall between its editorial content and its funders, but the foundation’s grant does specify the broad geography we should focus on (for more on the foundation’s role in Colorado River issues, see this series from Jeremy Jacobs of Greenwire).

Focusing on the seven states of the Colorado River Basin and Northwest Mexico leaves out a big chunk of the West, and we mean no disrespect to our friends in Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana. But with the limited resources of a start-up, we’d be on a fool’s errand to extend our coverage to that part of the country. If, however, The Water Desk can acquire additional financial support, I can easily imagine expanding to the Pacific Northwest, Texas or other regions!

The graphic below from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation illustrates the hydrologic boundaries of the Colorado River Basin and also adds another critical dimension: areas beyond the physical watershed that still depend on the river and its tributaries for their water supply, at least in part (see this post for more maps of the basin).

In and around the Colorado River Basin, we built herculean dams that turned rivers into reservoirs. We bored colossal tunnels through mountains. And we constructed a sprawling network of infrastructure to not only to move water uphill to desert cities such as Phoenix and Tucson but also to export the Colorado River beyond the watershed’s boundaries to supply Denver, Albuquerque, Salt Lake City and Southern California.

Basin states: one-fifth of U.S. population and economy

As director of The Water Desk, I can assure you that the region around the Colorado River Basin is more than enough to keep us occupied. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the seven basin states had 61.3 million residents in 2018, or 18.7% of the nation. Nearly two-thirds of the basin’s population lives in California, which is home to almost one in eight Americans. Looking at economic activity, the basin’s GDP of $4.2 trillion accounts for 20.3% of the national total, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

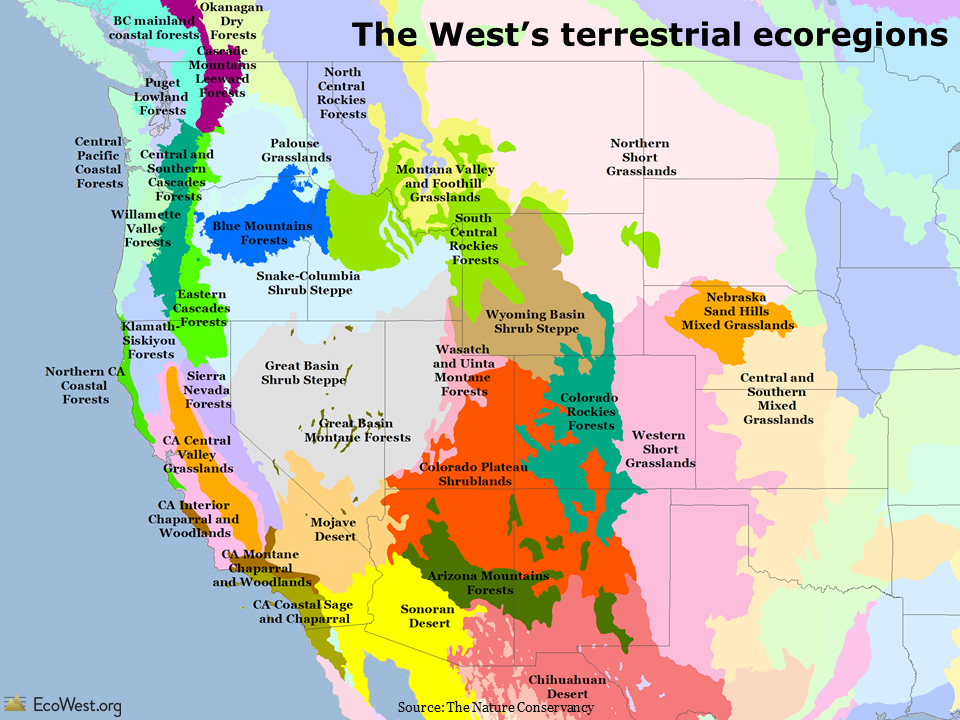

Within these seven states lie extremes in climate, topography, wealth, politics and people. The map below, which I created using data from The Nature Conservancy, shows that this one part of the country is also home to a tremendous diversity of ecoregions.

The West boasts an impressive spectrum of weather, elevation, vegetation, geology and cultures. But one thing that unifies the region is its rapid population growth over the past century or so. The Colorado River Basin accounted for just 2% of the U.S. population in 1850, when only a half-million people lived in the region that would eventually encompass seven states. Today, it seems like I see a half-million people in a single morning on Colorado’s I-70 while driving up to the mountains to ski a powder day.

A fundamental dilemma facing water in the West is that the region’s meteoric growth rate has deposited millions of people in places where there’s not a whole lot of water available without massive human interventions, which tend to be economically and environmentally costly. Most of California’s water is in the northern half of the state, but far more people live down south; in Colorado, most of the precipitation falls to the west of the Continental Divide, but the great majority of the population lives on the other side of the mountains.

Population growth and climate change are some of the defining challenges for the American West, especially its water resources. But there are certainly other threats, such as the armada of invasive fish, plants, crustaceans and other non-native species that are causing chaos in ecosystems already disrupted by human activity. In many areas, critical water infrastructure is crumbling and in need of expensive repairs.

As any water journalist will tell you, there is no shortage of news in the field and trying to keep up with it all can feel like drinking from a firehose. It’s our job to distill that ocean of information into something digestible for average citizens. Compared to guns, immigration, health care and other political issues, water may not be top of mind for most people, but I think there’s a deep reservoir of interest and concern in the public that we should be tapping into.

I hope you’ll come aboard and join us on this journey as we follow water issues! If you’d like to stay connected, please sign up for our email newsletter and follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.