As seasonal streams around the Colorado high-country dry up before winter, Stephanie Kampf rallies volunteers, a keen mix of retired scientists and college students, to help her map these waterways using a mobile app. Kampf, a professor of watershed science at Colorado State University, runs a crowdsourcing project called Stream Tracker to map and monitor small seasonal streams.

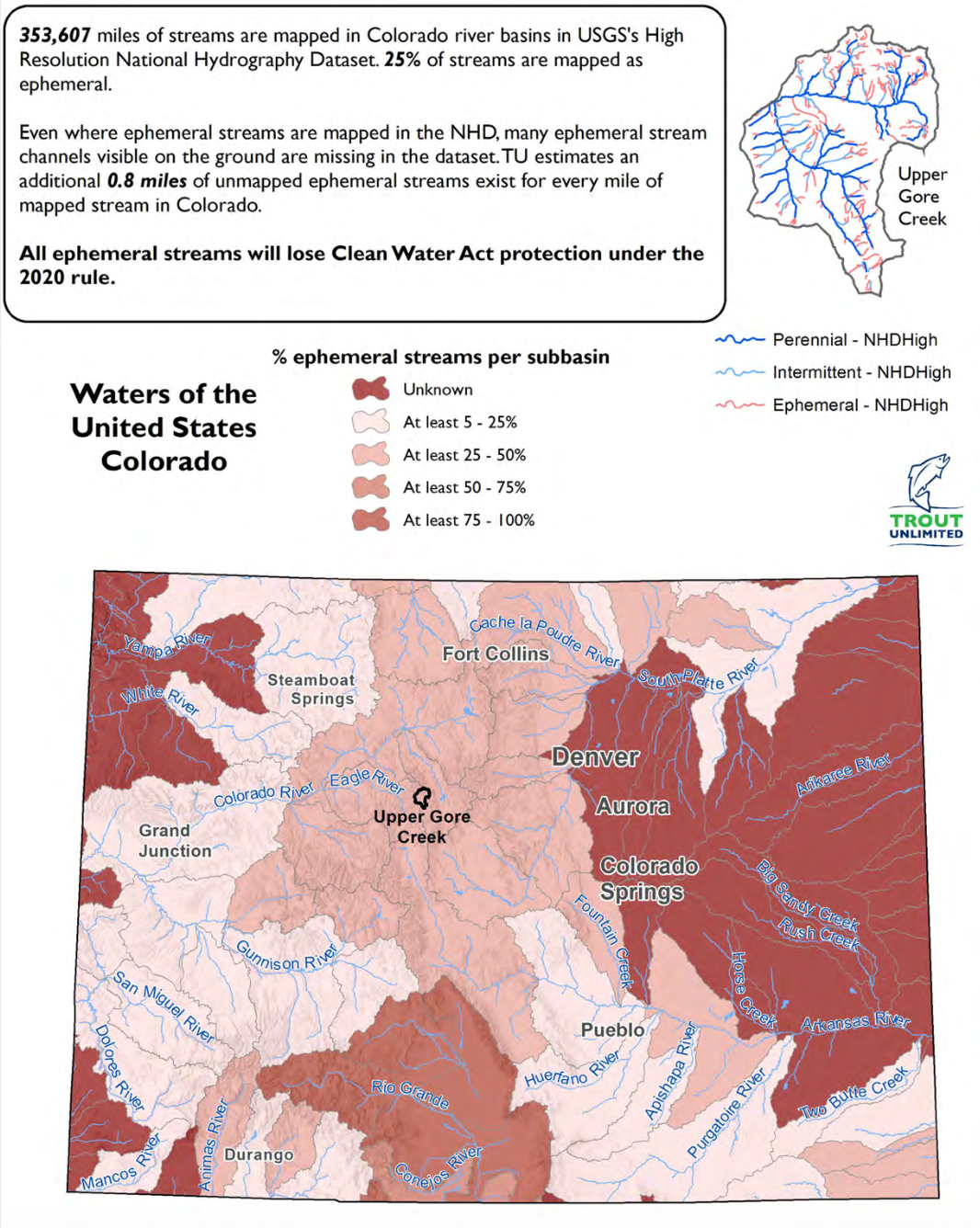

The official hydrography data used by water regulators, scientists and land managers—called the National Hydrography Dataset, or NHD—often misclassifies, misplaces or completely leaves out seasonal streams.

The project, launched in 2017, is one of several crowdsourcing programs that have emerged to improve data on small streams. Those waterways, termed ephemeral or intermittent depending on how often they flow, are dry much of the year and then activate during rain events or from seasonal snowmelt. They make up over 80% of all streams in the arid West, carrying snowmelt through a seasonal network that supplies the Colorado River and its tributaries, which provide water to 40 million people.

The central problem that inspired Stream Tracker is that the official hydrography data used by water regulators, scientists and land managers—called the National Hydrography Dataset, or NHD—often misclassifies, misplaces or completely leaves out seasonal streams. One study by the conservation group Trout Unlimited suggests that for every mile of mapped stream there’s about one more that’s unaccounted for in the NHD.

“We’d try to identify streams and go into the field and see that there was no stream there,” said Kampf of her attempts to use the NHD. “There was just not a good record of where the streams actually are.”

More accurate mapping of these water bodies could not only help researchers like Kampf but also give landowners and developers more clarity on whether a stream on their land is federally regulated.

On the federal level, the U.S. Forest Service needs to abide by environmental rules, such as riparian buffer zones, for conservation planning. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers needs to assess its oversight responsibility to permit new developments near regulated water. Emergency-response organizations need to predict and plan for flooding, particularly as landscapes are charred by wildfires.

“NHD is relied on so readily across the board by so many different people for their broader scale research,” said Helen Neville, senior scientist at Trout Unlimited. “It’s what everybody uses as the base layer for anything they’re doing having to do with aquatics.”

But after nearly 136 years of work, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the nation’s official mapmaker and the agency managing the NHD, is still trying to solve the problem of bad data.

By pushing to collaborate with states and making tweaks as new technology becomes available, the agency has been doubling down on its effort to improve the NHD in recent years. Now, as the agency dips its toes into crowdsourcing stream data, regular citizens can help speed up progress.

Several promising efforts are underway to improve and update the data both within the USGS and beyond, using everything from satellites to hikers armed with mobile phones. Even the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency earlier this year signaled that it wants to improve on stream data for its own regulatory reasons by creating a stream-mapping group that will work with, and help enhance, the NHD.

It remains unclear what, beyond initial talks, has materialized from the group. It also remains unclear how the Biden administration will handle this.

Mapping watersheds, and politics

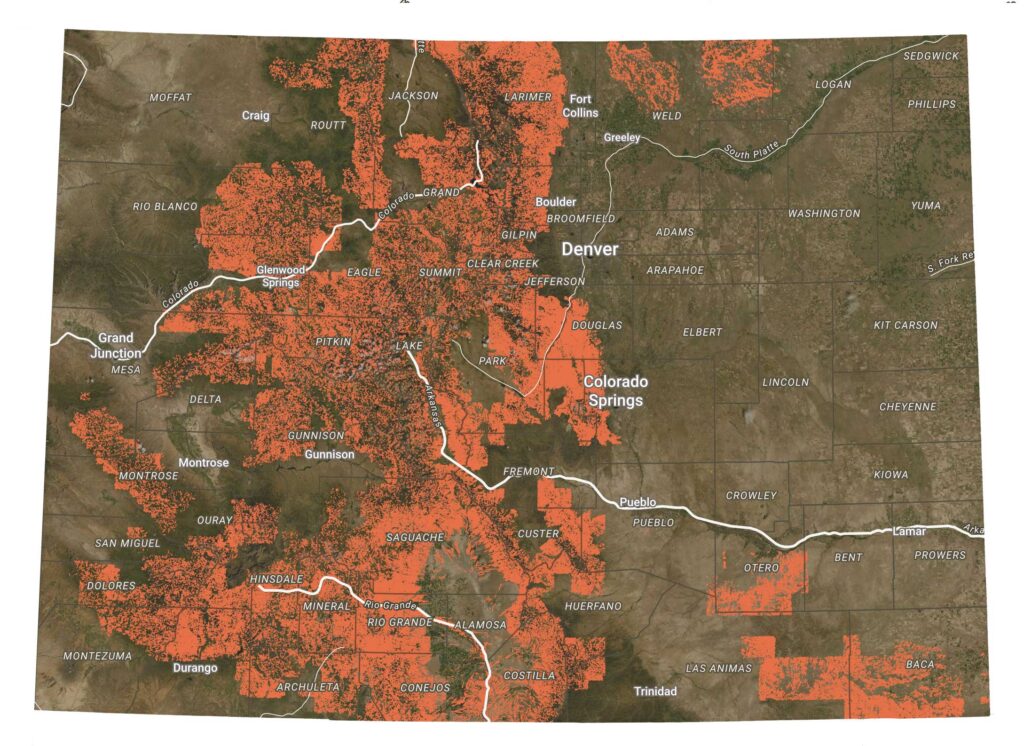

In January 2020 the Trump administration enacted a change to the landmark Clean Water Act, effectively removing federal oversight of ephemeral streams. The water-rule change, called the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, was criticized by many scientists and environmental organizations as a brazen rollback of the Clean Water Act. (See this Water Desk article for more information.)

In designing the rule change, the EPA disregarded its own research on ephemeral and intermittent streams, arguing that the issue should be left to the states. It also brushed off attempts by conservationists to analyze the rule’s impact because they used data from the NHD.

“That to us seemed like a copout,” said Kurt Fesenmyer, GIS & Conservation Planning Director at Trout Unlimited.

Many researchers see the NHD as the best available resource for this type of high-level analysis, so dismissing them altogether, to Fesenmyer, was like throwing out the baby with the bathwater.

After that pushback, the EPA summarized why the agency felt the NHD was not worthy of use in regulatory planning. Simultaneously, it announced the mapping group.

Formally called the Aquatic Resources Mapping Group, it will pursue “federal, state, and tribal partnerships.” According to Matthew Wilson, the Army Corps regulatory programs manager and a representative in the group, they will use the NHD and other datasets to create a new visual tool showing which water bodies are federally regulated across the country.

This will require accurately defining ephemeral and intermittent streams in order to be useful since different stream types have different rules, but it’s unclear how that will happen.

“The Aquatic Resource Mapping effort will strive to improve mapping of the nation’s aquatic resources, including streams and wetlands, by enhancing existing national products as well as methodologies for mapping and modeling aquatic resources,” said Wilson.

The Army Corps is one agency that could benefit from improved mapping, according to Wilson, given that it is responsible for doling out CWA permits for development on regulated water. The group’s leader, Dwane Young, chief of water data integration at the EPA, declined to comment on specific activities and future targets.

An EPA fact sheet from January on the issue of NHD deficiencies and the launch of a mapping group, says that developing maps of CWA jurisdiction “will promote greater regulatory certainty, relieve some of the regulatory burden associated with determining the need for a permit, and play an important part in helping to attain the goals of the CWA.”

Piecemeal improvement

If Wilson is correct, then the mapping group will attempt to enhance the national mapping effort, thus overlapping with the work of USGS.

Over the last two decades, the USGS has been digitizing stream data into the NHD and improving its models using a grab bag of different techniques. But the USGS knows there is still much to improve upon, especially in the way data is collected. Currently, states are responsible for their own data collection, and mapping priorities differ from place to place. This means you can see distinct grids in the NHD that create a patchwork of unmapped landscapes, mapped areas with old data and, more recently, updated areas with the finest detail.

One of those finer details is what’s known as flow regime, or the seasonality of a stream: is it always flowing (perennial) or only temporarily after rain or snow (ephemeral)? This is where, according to Matthews, the EPA mapping group will need to focus some effort since he says the NHD doesn’t currently provide this information, or at least not uniformly.

The group is looking into using crowdsourced data from efforts like Stream Tracker to help define flow regime, since seasonality is one of the elements being tracked by the project. Wilson said this information would help the Army Corps more efficiently respond to Clean Water Act permit requests, which require determining if a stream is ephemeral, and thus unregulated.

Cue the lasers

Beyond making regulatory processes more transparent and streamlined, improving the NHD broadly benefits scientists and land managers around the country. Fesenmyer’s work at Trout Unlimited is part of a growing body of science that relies on the NHD, including 25 research papers so far in 2020.

One example is a five-year study, funded by NASA, that Neville co-authored in 2018. The study analyzed the extinction risk facing Lahontan cutthroat trout populations in Nevada, California and Oregon. The NHD was the basis for the team’s modeling work in that study.

“Fundamentally, it’s the first piece of information we need to know—where trout populations live and how big of a habitat they have,” she said.

In order to ensure their model was accurate, Neville’s research team had to use a satellite remote sensing technology to improve the accuracy of the data.

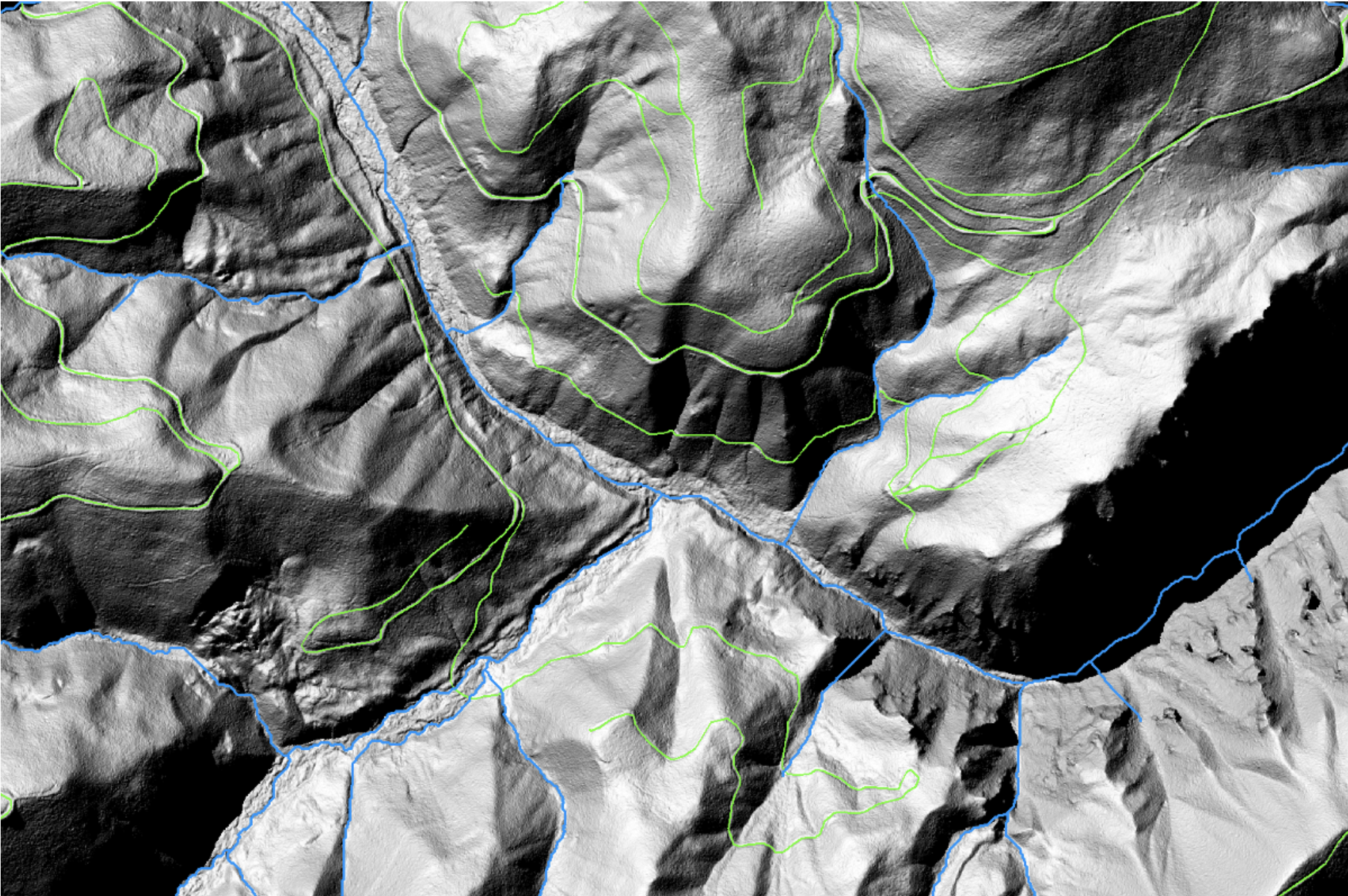

More and more, researchers are making use of another important advancement in order to acquire more accurate data. Using laser imaging, called lidar, scientists can remap study areas to achieve much finer detail. Many see this as the most promising advancement in data collection for hydrography mapping.

Lidar is a high-resolution aerial-imaging process that uses a laser to measure the distance to the ground from either an aircraft or satellite to create three-dimensional elevation models. Since scientists know the approximate topography on which ephemeral streams can run, identifying those spots on the three-dimensional map is a good way to increase the accuracy of the NHD, according to Fesenmyer.

“Typically right now lidar is collected from a plane, and that’s an expensive high-effort deal,” he said, adding that it would be more desirable to have a space-based lidar sensor that uses satellites to collect data universally and at a more regular interval.

A satellite making regular laps around the Earth to capture new data for the NHD will be a huge upgrade, but crowdsourcing projects like Stream Tracker will still be needed to verify what’s seen on the ground. As of late 2020, 70 percent of the country had been mapped using lidar, including 73 percent of National Forest System land in the Southwest, 55 percent in the Rockies. The NHD won’t be able to use that upgraded data for some time due in part to the need for more computing power, according to Fesenmyer.

“Personally, I’d like to see this ephemeral data revised on a statewide level using lidar to better identify potential ephemerals,” said Chris Brown, GIS mapping coordinator for the Colorado Division of Water Resources.

Toward that end, the USGS has developed a program designed to help fund state lidar programs. The goal is to acquire high resolution data across the country by 2023, according to the website.

Crowdsourcing efforts are a promising complement to technical advancements like lidar—so much so that in August, the USGS launched its own version of Stream Tracker, called FLOwPER (for “flow permanence”), to gather data and incorporate it into the NHD. Along with the EPA’s aquatic mapping group and technological upgrades, crowdsourcing could add value by helping verify that the maps are still accurate since, according to Neville, climate change is altering the aquatic landscape.

“Efforts like Stream Tracker and others can be used to help improve the NHD, in terms of overall improving accuracy of a streamflow classification as well as working towards a more dynamic NHD,” said Kristin Jaeger, research hydrologist at USGS.

Trust but verify

Brown of the Colorado Division of Water Resources helps verify new data for the NHD. That data, he said, typically comes from the Forest Service and other government employees who are regularly out in the field. He hasn’t seen any Stream Tracker data come through his desk in Colorado, but he said that in order to incorporate such data, an extra filter would need to be applied “to confirm its trustworthiness.”

Nonetheless, crowdsourcing hydrography data is gaining traction.

Kampf and her team of budding and seasoned scientists will continue to collect stream data for partners at the Forest Service, EPA and others to explore.

Kevin Teiken, known as “Water Otter” on his Stream Tracker profile, is a natural resources management major at Colorado State University, and one of Kampf’s students. He joined the project as a volunteer in September and has already contributed nearly 20 observations. He said the area around his house in Fort Collins hadn’t previously been mapped, according to the mobile app.

Teiken began participating in the mapping project for a class, but has continued because he said it’s a good motivator to explore new areas on foot.

“I’ve found four or five irrigation or drainage ditches that only fill with rain that were completely new observations,” he said.

Longform Story CSS Block

This story was supported by The Water Desk.