Nestled at the headwaters of Lefthand Creek, a mile south of Ward, Colorado, sits the Captain Jack Mill. From 1860 to 1992, the area was a hot spot for gold and silver mining and though the tunnels of the mine have long been empty, the legacy of pollution continues to damage nearby waterways, aquatic life and drinking water.

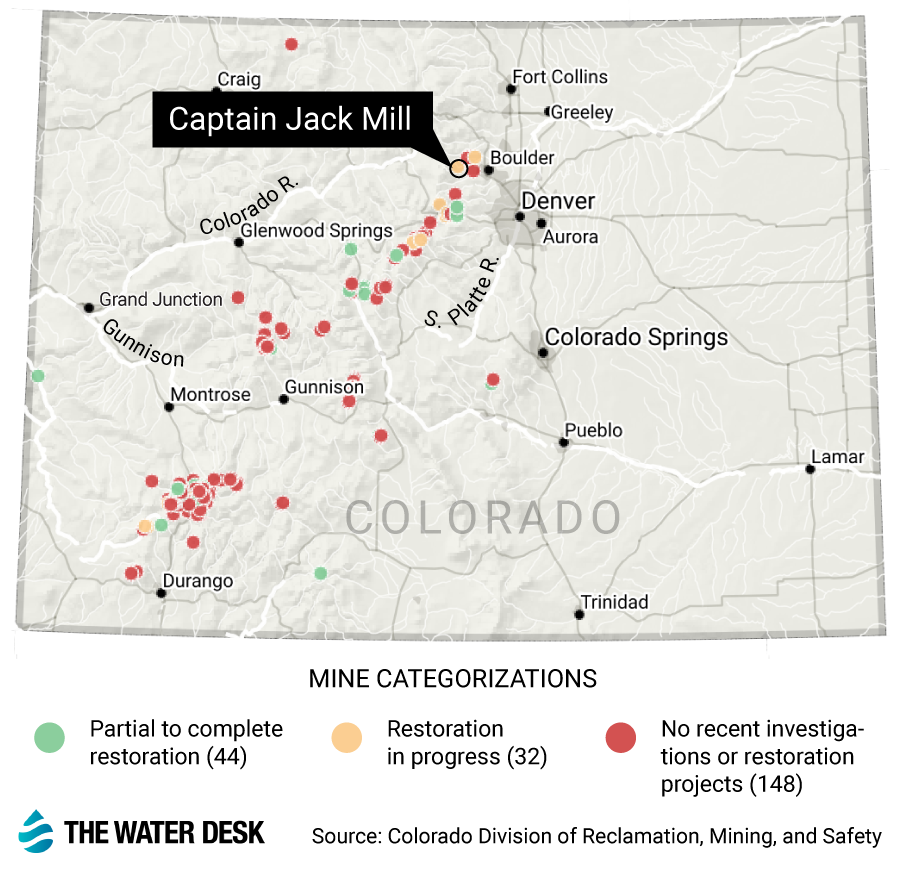

According to a 2017 study, there are over 23,000 abandoned mines across Colorado and 1,800 miles of streams that are impaired due to pollutants related to acid mine drainage.

The pollution is formed when pyrite (an iron sulfide) is unearthed during mining operations and chemically reacts with air and water. The reaction forms sulfuric acid and dissolved iron, which causes the red, orange or yellow sediments that can be seen at the bottom of contaminated streams. The acid runoff can further dissolve heavy metals such as copper, lead and mercury, which can then leach into and contaminate streams, lakes and groundwater.

That’s what happened in 2015, when the Animas River turned orange after workers accidentally released toxic wastewater from the Gold King Mine in southwest Colorado.

Acid Mine Drainage Sites Span Colorado’s High Country

In Colorado and beyond, acid mine drainage has the potential to pollute vital waterways long after mineral extraction has ceased. Part of the problem is the lack of environmental safeguards put in place in the late 1800s, when mining operations started to boom. By the time the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act was enacted in 1977, much damage had already been done.

“Most of the books that address these kinds of problems often start off with, ‘Mines from the Roman times are still generating acid mine drainage,’” said Joe Ryan, an environmental engineering expert at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Working with the nonprofit Lefthand Watershed Center, Ryan traced the source of dissolved metals contaminating the Left Hand Creek watershed, which provides drinking water to 20,000 customers.

In 2004, Ryan and a team led by the University of Colorado’s Alice R. Wood released a report that ranked the Big Five Tunnel at Captain Jack Mill as high priority for reclamation, shortly after the mine was designated as a Superfund site. Even so, it took more than a decade for a remedy to be implemented.

Cleaning up the past

In 2016, the EPA attempted to plug up the mine’s opening by filling the mouth of the Big Five Tunnel with limestone and a bulkhead valve. The limestone was meant to decrease the acidity of the water that collected behind the valve so that it was less harmful to the creek.

But it didn’t quite work.

When the water was released from the bulkhead seal inside the Big Five Tunnel in October 2018, it was too acidic and polluted a five-mile stretch of the river, leaving hundreds of dead fish in its wake.

Following the 2018 release from the tunnel, a portable treatment system was installed to process water from the bulkhead valve before it flows into Lefthand Creek. Though effective, this method is an expensive addition to the already steep cleanup costs.

“There have been anecdotes about fish being back in locations that they haven’t been seen in for quite a long time,” said Ryan, who plans to revisit Lefthand Creek to determine if the cleanup efforts have improved the stream’s water quality.

Between 1998 and 2003, the U.S. Forest Service estimated that more than $310 million was spent cleaning up acid mine drainage around the country.

“I think people didn’t really understand the connection between some of what they were doing and the long-term impacts associated with it,” said Jeff Graves, director of the inactive mine reclamation program for Colorado’s Department of Natural Resources. “These old miners that did the work weren’t bad guys, they just had a different mindset.”

Graves, who helps enforce mining regulations in the state, assesses and develops plans related to the safety and environmental impact of legacy mines, including those designated as Superfund sites like the Captain Jack Mill. Though some of these plans may take many years to implement and will include decades of monitoring, Graves remains positive.

“It’s a finite list and each one that we work through is one less that we have to next year,” Graves said. “We’re getting there one step at a time.”

Of course, pollution from legacy mines is not just a problem in Colorado. The National Association of Abandoned Mine Land Programs, which includes 23 states and three tribes, lists acid mine drainage along with underground mine fires and landslides as major hazards.

Climate change could worsen problem

When Diane McKnight began to research acid mine drainage in 1978, she thought that it was a problem on the verge of a solution.

“It became clear that these are really wicked problems with a lot of challenges,” said McKnight, founding director of the University of Colorado’s Center for Water, Earth Science and Technology and former researcher with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Part of McKnight’s research focuses on how climate change may increase acid mine drainage. She has observed large decreases in stream pH during summer months, which she believes is due in part to rising temperatures. McKnight and other scientists theorize that the intense warming and drying of the soils allow more pyrite to oxidize. As temperatures continue to increase due to climate change, warmer and longer summers could mean more acidic streams.

The Colorado Water Plan, released by the state in 2015, acknowledges that with growing demand for water, ongoing pollution from legacy mines is a water quality concern that needs to be addressed as Colorado faces a possible doubling of its population by 2050.

McKnight is optimistic that advances in science and technology will yield effective options for stream remediation. Just as robotics have been used to explore planets in space, McKnight wonders if they can be utilized for remote cleaning of acid mine drainage, especially in the winter months in Colorado, when avalanches pose threats.

“We can figure this out,” McKnight said. “This is an avenue to meet some of Colorado’s water needs in the future.”

Longform Story CSS Block

Download media from this story

Photos, video, and the map used in this story, plus additional unpublished, full resolution media, are available in the Captain Jack Mill media gallery page on our website.